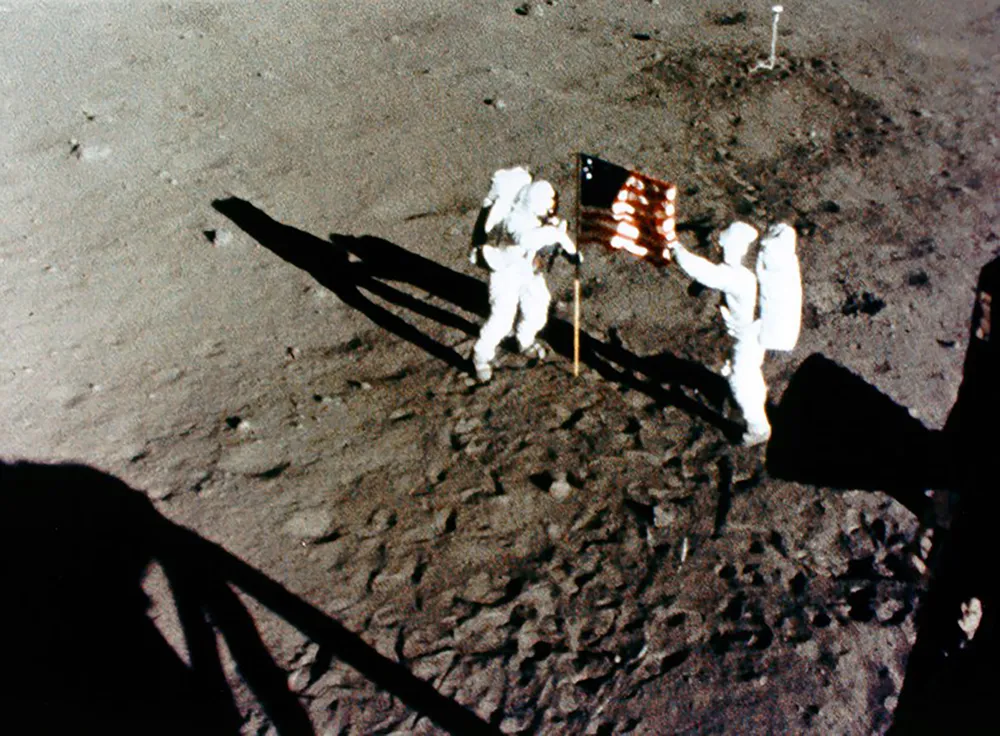

On 20 July 1969, Apollo 11 astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin took their first steps on the Moon. But how did this monumental achievement change life as we know it, and what effect does the Apollo programme have on our life today?

Historians in 1969 had little idea whether Apollo would change the world.

On the night of the Apollo 11 landing, British historian AJP Taylor stated in a TV interview how he doubted the event would make any difference to the course of human history.

But it seems clear now that the six Apollo Moon landings did alter the world in many ways, covering the short, medium and long term.

The decision by the United States to land on the Moon before the end of the 1960s was born out of the ideological Cold War with the Soviet Union, which had been ongoing since the 1950s.

A precursor to the Apollo missions had been those of the Mercury Seven, who laid the groundwork for putting human feet on the Moon.

When President Kennedy addressed Congress on 25 May 1961 seeking support for the Apollo project, he spoke of how the US had to compete technologically and politically during the ongoing Cold War, saying: “If we are to win the battle that is now going on around the world between freedom and tyranny… it is time for a great new American enterprise.”

Kennedy took the initiative, realising that there were geopolitical and economic reasons to invest government resources in advanced technology.

Eventually over 400,000 Americans would work on the Apollo programme.

The Moon Race became a test of ideological systems. Apollo 8 astronaut Frank Borman described his December 1968 flight around the Moon as “a battle in the Cold War”.

The Space Race is on

By spending a peak of over 4 per cent of its federal budget on space in 1965 and 1966, the US gained huge geopolitical and economic prestige.

The USSR had committed approximately half the US funding level, but had failed in its own attempts at a Moon landing project, which had started in 1963 in response to Apollo.

The US success saw the nation through the dark days of the Vietnam war to the early 1970s. Arguably, Apollo changed short and medium term geopolitical and economic history between the 1970s and 1990s.

By 1991 the Soviet Union had collapsed, ending the Cold War.

There is no doubt that the Apollo programme, undertaken openly for the world, had strongly contributed to the outcome of this superpower battle.

It was, according to many political commentators, like “fighting a war without direct casualties.”

There was more to Apollo than political posturing, however.

In Kennedy’s historic 1962 ‘we choose to go to the Moon’ speech he said Apollo could “in many ways hold the key to our future on Earth”.

Futurist space writers like Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, HG Wells, Olaf Stapledon and Arthur C Clarke had always proposed that humanity’s early exploration of the Solar System would represent a new destiny in the evolution of Homo sapiens as a species.

Armstrong’s carefully crafted words, “one giant leap for mankind”, recognised the symbolic change that was happening at this time.

On the night of the Apollo 11 landing, British historian AJP Taylor stated in a TV interview that he doubted the event would make any difference to the course of human history.

After two million years of the evolution of Homo sapiens, humankind had reached the stage of being able to travel across interplanetary space – it had become a spacefaring species.

Tsiolkovsky’s deep words, “the Earth is the cradle of humanity, but one cannot live in the cradle forever”, were being fulfilled.

Yet, rather than making us look out at our future beyond our planet, perhaps one of the programme's most lasting legacies was changing how we looked at our own planet.

During the Apollo years of 1968-72, worldwide environmental concerns became evident.

Pressure groups like Friends of the Earth and Greenpeace were established, while a report titled ‘The Limits to Growth’ set out what would happen to the planet should the population continue to grow and expand unchecked.

Environmentalist James Lovelock created his Gaia theory, viewing Earth as a self-regulating biosystem.

A new perspective

We have Apollo to thank for the powerful motivational images of this vulnerable planet taken from 384,000km away.

The Earthrise photo from the 1968 Apollo 8 mission resonated with the public in an unexpected way.

Allied to other images such as the famous Blue Marble whole-Earth photo taken by Harrison Schmitt in 1972, there was a striking change in our perception of the lonely Earth as an oasis of life in the cosmos.

As Anders said of the Apollo 8 mission: “We came all this way to explore the Moon and the most important thing is that we discovered the Earth”.

Beyond this, an Apollo legacy must be the hope for future planet-wide initiatives.

The global-level inspiration that the Moon landings provided means projects like the reduction of carbon emissions could be seen as more viable, provided nations followed the emerging ‘we can land on the Moon and therefore achieve anything’ approach, with sufficient financial investment.

An example is the encouraging CFC reduction following a UN-led initiative – this used Apollo 17's Blue Marble image of Earth.

We came all this way to explore the Moon and the most important thing is that we discovered the Earth.

Apollo lunar module pilot William Anders

An age of invention

If the political will is there, similarly Apollo-inspired efforts might well help feed the planet, properly attack world poverty and disease, plus of course address CO2 reduction internationally.

A key gift of Apollo, identified by space historian and film-maker Chris Riley, is the technological stimulus provided by the hi-tech nature of the NASA Moon programme.

Many practical products developed by NASA during the Apollo years are well known: cordless drills, PV (solar) panels, freeze-dried food, thermal insulation material, heat coatings and so on.

But Riley has also recorded how NASA approached Massachusetts Institute of Technology to develop a small, lightweight computer to fit into the Apollo spacecraft.

The computer used reliable integrated circuits and NASA placed an order for one million of them from the Fairchild Semiconductor company.

This financial kick-start to the industry prompted two Fairchild employees to leave and form Intel in 1969.

From this, the computer revolution of the 1970–2000 period developed, leading to small PCs, smart phones, the internet and dot-com industries.

The technological gift from Apollo accelerated computer technology perhaps by 10–15 years, thanks to the knock-on effect within the industry.

Apollo also had a powerful inspirational effect on young STEM graduates across the world – there were three times more engineering and science PhDs following Apollo.

Professors Brian Cox, John Zarnecki, Martin Sweeting and World Wide Web inventor Tim Berners-Lee have referred to the inspiration of Apollo, while space entrepreneurs like Richard Branson, Elon Musk, Paul Allen and Jeff Bezos have all noted their own ‘Apollo effect’ calling.

Apollo was a world experience – 500 million watched the Moon landing in 1969, a fifth of the globe’s population.

Culturally, it can be argued that the ‘can-do’ attitude of NASA from the Apollo years is now respected on a worldwide scale.

The visceral and heroic nature of the human spaceflight adventure has become fascinating to young people in recent years, thanks to movies like Apollo 13 (1995) and First Man (2018) (both of which feature in our guide to the best space movies of all time).

Real space travellers, like the UK’s Tim Peake and the reluctant hero Neil Armstrong himself, are new role models.

Another key legacy of the Apollo Moon landings must be the deep philosophical consequence of mankind knowing that it achieved the extraordinary.

The common view of Apollo and the desire to ‘choose to go to the Moon’ is arguably at the core of the human spirit, with a common desire to explore and venture as far as possible from home – “because it’s there,” as Everest climber George Mallory put it.

There are new worlds to explore beyond Earth orbit and Apollo’s success confirmed that the dream of deep space travel is indeed achievable.

The Apollo message was highly emotional for many – Arthur C Clarke said at the launch of Apollo 11, “I cried for the first time in 20 years! … This is the last day of the old world”.

Apollo's scientific legacy

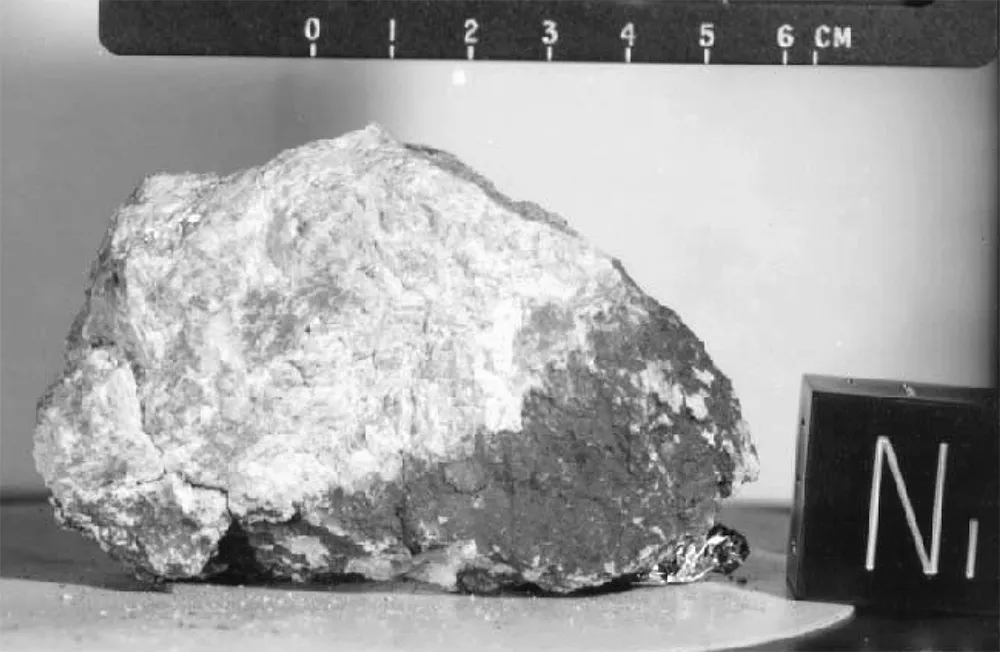

While the first three Apollo missions were intended as a precursor to fuller lunar exploration, Apollo 15 to 17 opened up a detailed geological study of the Moon.

The crews found that the Moon has evolved over its 4.6 billion-year lifetime, being melted, erupting and impacted many times.

The Moon rocks brought back were similar in composition to Earth’s, although lacking iron and elements that could provide an atmosphere.

Samples as old as any on Earth were discovered, with the Apollo 15 ‘Genesis Rock’ dating back 4 billion years.

Thanks to Apollo, lunar cratering is now better understood, and Earth, Mars, Venus and Mercury's cratering rates have been clarified.

Lunar mascons – areas where the lunar mass is more concentrated – were discovered beneath lunar basins, originating from impacts 3.2–3.6 billion years ago.

Theories explaining the difference between the thicker crust of the lunar far-side and the thinner Earth-facing side are now emerging.

As well as what the Apollo astronauts brought back in Moon rocks, scientists have learned from what they left behind, as laser reflectors placed on the surface by Apollo show that the Moon is slowly drifting away from Earth at a rate of about 4cm per year.

Return to the Moon

The last decade has seen a renewed interest in making the journey back to the lunar surface.

Apollo cost $160bn at today’s prices. Due to huge US spending on the Vietnam War, social deprivation and other concerns at home, in 1972 President Nixon cancelled the last three planned Apollo missions.

Saddened at the cuts, Arthur C Clarke said at the time: “The Solar System was lost, at least for a while, in the paddy fields of Vietnam,” but then later noted, “in the long perspective of history, a few odd decades of delay does not really matter.”

Post-Apollo ambitions, like NASA’s Project Constellation Moon return plan, did not work due to lack of funding, but in the last five years there has been renewed interest across the world, fired by water-ice discoveries at the lunar poles.

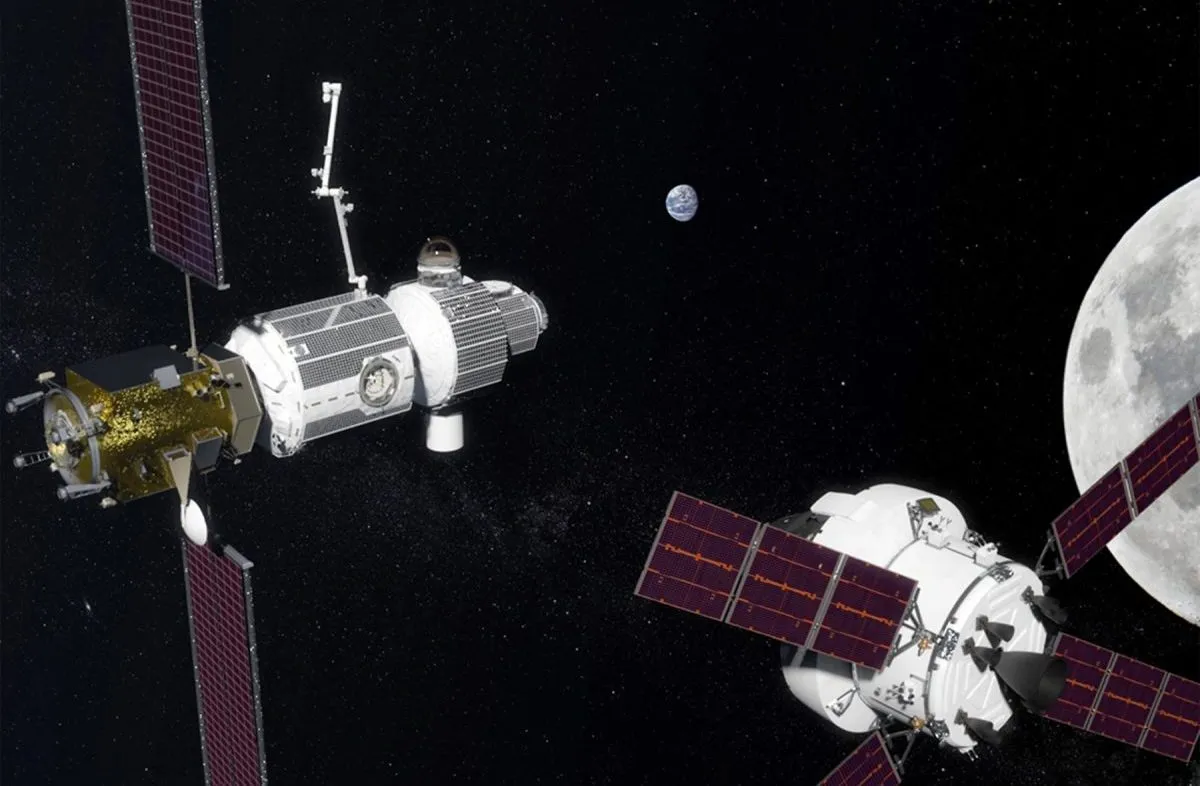

Following President Trump’s Space Policy Directive 1 in 2017, NASA is developing the Lunar Orbital Platform-Gateway space station, with European, Japanese and Canadian support.

Landing missions may occur by the late 2020s. Recently, Vice President Mike Pence called for a US return to the Moon as early as 2024 – an endeavour now called the Artemis mission.

Though President Trump has requested an additional $1.6 billion to NASA’s 2020 budget, many at NASA consider this too much of a challenge, and 2028 is probably the more realistic date.

The driving phrase from space agencies now is, “this time we will stay”!

After Apollo: key lunar events

1976 Luna 24 returns limited soil samples to Earth

1990 Japanese Hiten orbiter

1994 NASA’s Clementine observes the Moon

1998 NASA’s Lunar Prospector orbits

2006 SMART-1, ESA orbiter; intentionally crashes

2007 Japanese SELENE orbiter

2009 Chinese Chang’e 1 orbits; crashed deliberately

2007–15 Google Lunar X prize challenges private companies to land on the Moon

2008 Indian Chandrayaan 1 impacts – water discovered

2009 NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter takes detailed survey 2015 International Moon Village idea promoted by ESA

2017 Space Policy Directive 1 plans for US return to the Moon

2019 Chinese Chang’e 4 lands on the far side

2019 Israeli SpaceIL Beresheet probe crashes during landing

The future?

2021 Luna-Glob, Russian polar lander

2023 Chang’e sample return missions

2023 NASA/ESA Orion manned orbital flight EM-2

2024 Potential SpaceX lunar missions

2028 NASA-led Moon orbiting station, the Lunar Orbital Platform-Gateway

2030 International lunar outpost or village established at the South Pole.Partly self-sustaining via in situ resource utilisation

2030–40s Lunar water for fuel and air, accelerating future exploration of Mars and the Solar System