The Moon - yes, our Moon, the one that orbits planet Earth - is rusting, even though theoretically speaking, it shouldn’t be.

Rust is what happens when iron meets water and oxygen.

Water provides the catalyst that enables the iron and oxygen molecules to react with one another and form the particular type of iron oxide known as ‘hematite’ or, more simply, as ‘rust’.

The reason Mars appears red, for instance, is that many millions of years ago, when the planet had liquid water and more of an atmosphere, the iron-rich rocks in its regolith reacted with oxygen and water to form rust.

Are you starting to see the problem here? The Moon isn’t supposed to have any oxygen, or any liquid water.

So while there’s plenty of iron in Moon rocks, that iron should be free from rust.

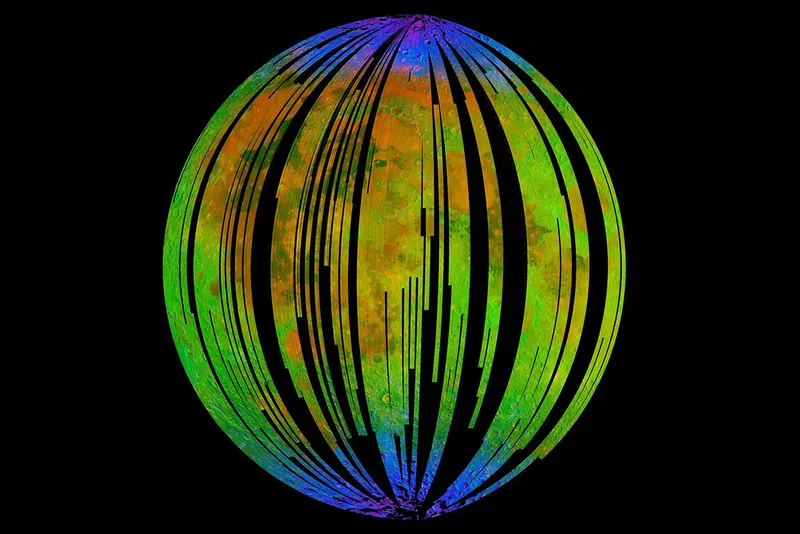

And yet in 2020, data sent back by India’s Chandrayaan-1 space probe clearly revealed the presence of hematite on the lunar surface.

So what's going on?

Scientists now believe the Moon is rusting because of the Moon’s interaction with Earth’s magnetic tail.

This is a stream of particles that have been first trapped by the Earth’s magnetic field, then ‘blown’ out of it by the solar wind.

The Moon passes through Earth’s magnetic tail for roughly six days of each 28-day lunar cycle (around the time that it’s full).

And during those six days, a small number of oxygen molecules from Earth could be making it to the Moon.

That explains where the oxygen part of the equation comes from, but we’re still left needing water before rust can form.

There is, of course, water on the Moon – but only in the form of polar ice

So it’s believed the observed hematite may have been formed in the Moon’s polar regions before being distributed elsewhere on the surface by a process or processes unknown.

More on this slow-developing story when we have it!

And in case you're wondering why the Moon appears orange sometimes, don't worry. It isn't rust!

A full Moon close to the horizon appears rust-coloured because of light scattering caused by Earth's atmosphere.