A long-time observing friend of mine brought up the idea of observing green stars, and a social observing project began to see how many of these emerald spectacles I could find in the night sky.

Bright stars may appear red, orange, yellow, blue or white. Noticeably absent from this palette is green stars, even though the human eye is most sensitive to green light.

Instead, a pair of double stars with different-coloured components interact in such a way they may give the impression that one of the stars is green or bluish green.

A small handful of 'green' stars are worth seeking out and make for a fun observing challenge.

For basic stellar astrophotography, read our guide on how to photograph the stars.

More observing challenges:

- 10 autumn binocular astronomy targets

- 8 Messier objects to spot in the night sky

- 6 planetary nebulae to spot in the night sky

The colour of stars

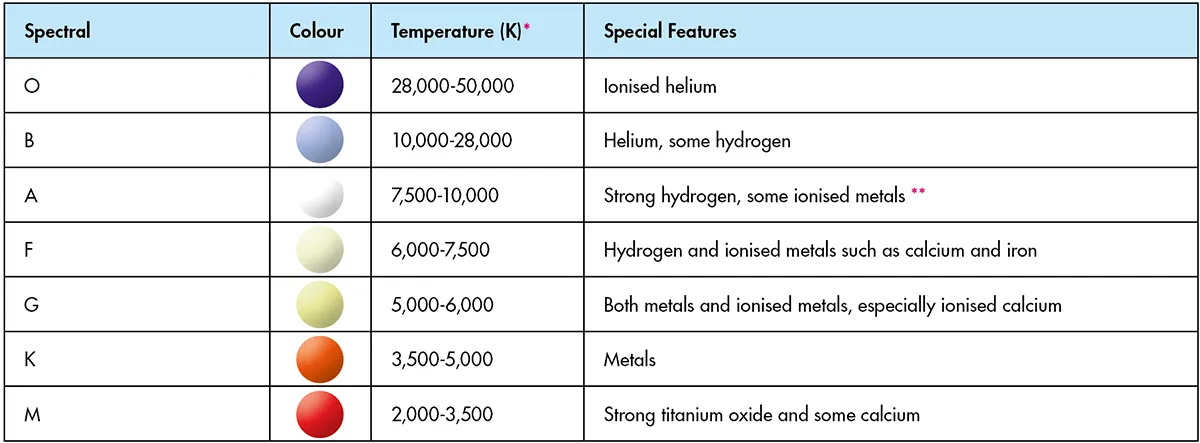

Stars seem to appear in almost every colour of the rainbow, and both eye physiology and the spectrum play a part (see the table above).

Some stars like Sirius can also change colour as a result of the distorting effects of Earth's atmosphere, and this is why stars twinkle. It is possible to capture this in an astrophoto showing the changing colour as the star twinkles.

The novice observer may detect no colour in stars but, in fact, any star has an apparent colour that is detectable with photometry.

The star’s light can be filtered so that separate colour components (wavelengths) can have their brightness measured.

The brightness of a star’s light also determines whether the human eye can detect a colour.If a star’s light isn’t bright enough to stimulate the eye’s cones, we see no colour.

The rods in the eye are more sensitive to light, but only detect shades of grey. Thus, a bright star may appear to have colour, while a dimmer star may appear only whitish or greyish.

For more on this subject, read our guide to the colour of stars.

How to observe green stars

Observations in this feature were made with an 8-inch reflector and rather clean eyepieces. Visual impressions at different magnifications are included.

Many of the green stars on our list are bright so they can be examined successfully with binoculars or small telescopes, but colour may be difficult to tease out without higher magnification and moderate aperture.

A steady mount is required for binoculars and steady seeing is a must.

Your results may not match those of another observer, but it is an enjoyable exercise to compare results with your observing companions.

Don’t be surprised if there is great debate among participants! You may find that telescope aperture, magnification, local light pollution and age of the eye affect your findings.

Also, your first impression of colour may be a green hue, but the longer you look at a star, the less green and more blue or yellow it might appear. Any of these results should be noted among your observations.

Download Deep-Sky Planner, Argo Navis and SkySafari files to help your automated telescope find Phyllis’s green stars. Click here to download.

1

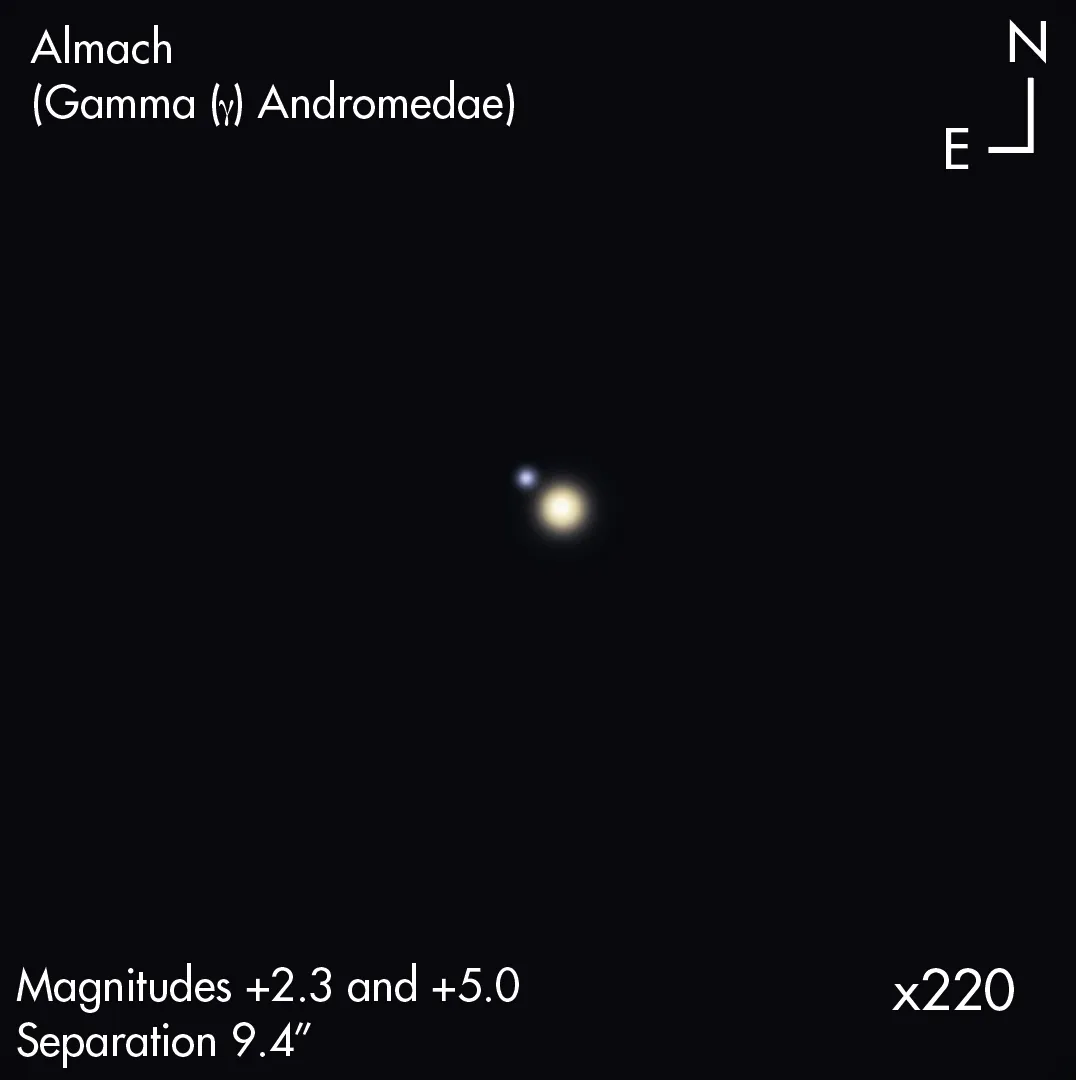

Almach (Gamma (γ) Andromedae)

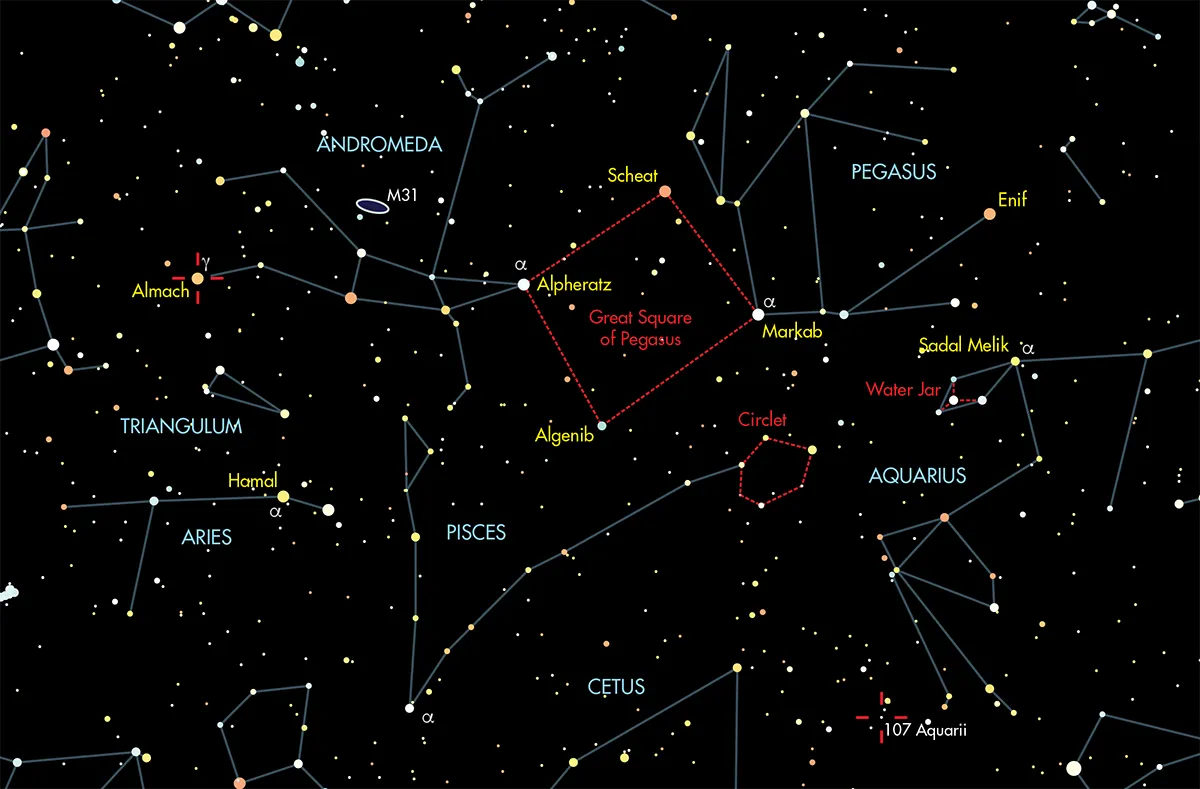

Although a close pair separated by 9.4 arcseconds, Almach is not difficult to split. It is the third in a line of bright stars extending eastward from Alpheratz (Alpha (α) Andromedae) in the northeastern corner of the Great Square of Pegasus.

From mag. 2.0 Alpheratz, move 7° northeast to mag. 3.3 Delta (δ) Andromedae, then a further 8° northeast to mag. 2.0 Mirach. Finally, move 12.5° northeast to find Almach.

The brighter A component is spectral class K3 that appears gold at 63x magnification. The fainter B companion – noticeably dimmer at mag. 4.8 – is actually a triple star system in itself.

With all three components in such close apparent proximity to each other (under 0.2 arcseconds) they appear as one blue star to all but the very highest specification amateur equipment.

Two of these components are type-B main sequence stars orbiting each other. The other is a type A0 star, which may possibly be the reason they merge to take on a greenish hue at 200x.

2

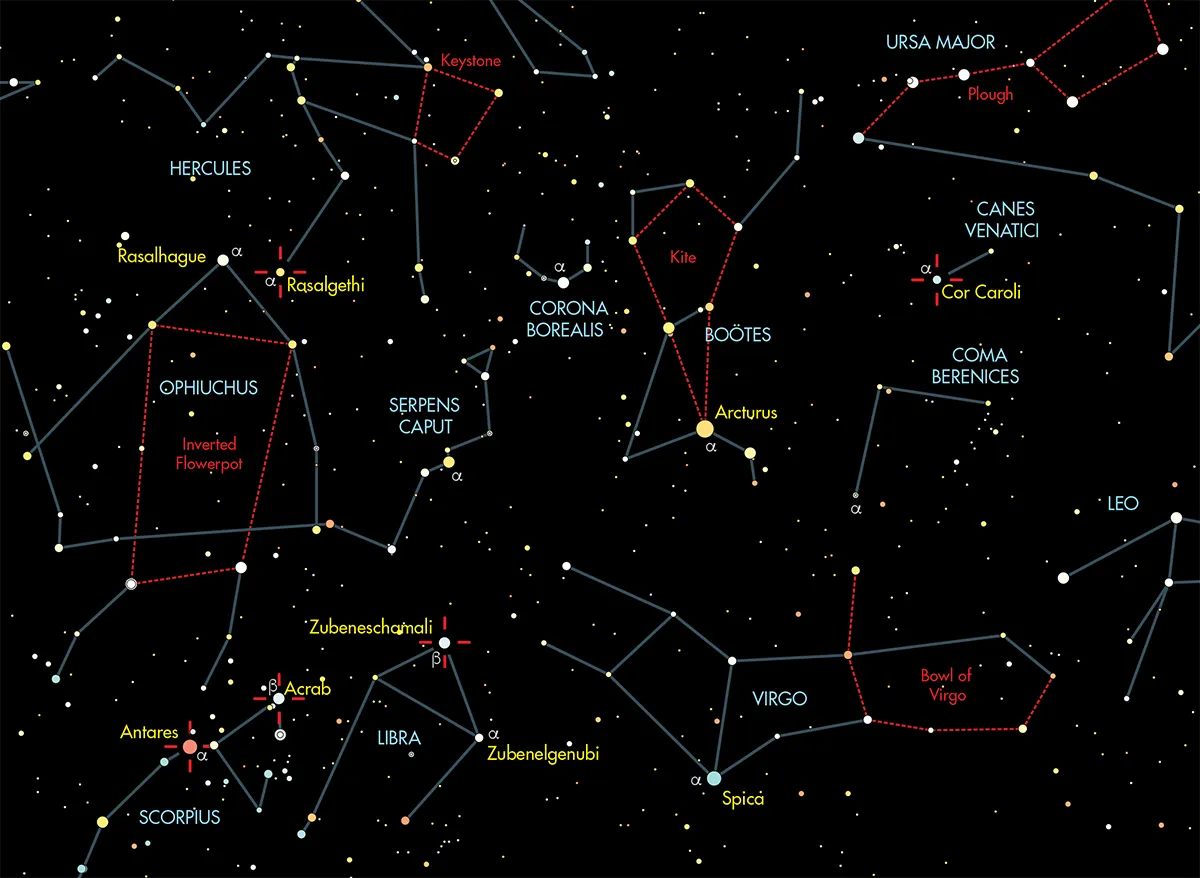

Cor Caroli (Alpha (α) Canum Venaticorum)

A radiant pair with 19.3 arcseconds of separation, Cor Caroli makes for an easy split at lower powers.

The brightest point of light in the constellation of Canes Venatici, the Hunting Dogs, Cor Caroli (the name means ‘Charles’s heart’) is easy to spot – it’s the brilliant star 10° south and 10° west of Eta (η) Ursa Majoris, which marks the end of the Plough’s handle.

Both components are spectral type A0 but their colours are not identical. They are mag. 2.8 and mag. 5.5 respectively, so identifying the components is easy.

At 62x magnification, the A component appears creamy yellow while the B component comes across as a pale yellow-green. Go to 185x magnification, though, and the B component takes on a pale blue-green tinge.

3

Acrab (Beta (β) Scorpii)

Take the opportunity to observe these stars when they are highest in the sky at your location, because while, at 13.7 arcseconds, they may be an easy pair to split, they don’t rise very high in the sky at northerly latitudes.

Acrab is a B0-type star located in a star-filled region of Scorpius near the plane of our Galaxy. It is one of the brighter stars in the northernmost claw of the Scorpion.

Beginning with Antares, the brightest star in the body of the Scorpion, move 7.5° northwest to mag. 2.3 Delta Scorpii. This is the middle star in a 6.5° line of mag. 2.0 stars orientated nearly north-south.

Acrab is the northernmost star in this line, about 3° north-northeast of Delta Scorpii. It is actually the tip of the northern claw.

The main component is a B1 spectral class star that appears warm white at 62x magnification. The fainter component is a B2 class star that appears pale blue-green at moderate (62x) and higher powers (200x).

4

Antares (Alpha (α) Scorpii)

The most challenging pair on our list to separate visually is this bright, naked-eye star in the heart of Scorpius. It appears orange to most observers, but when examined carefully in steady skies with enough aperture, you can see that the star actually comprises two components, separated by just 2.5 arcseconds.

Alpha (α) Scorpii does not give up its component pair easily, and not just because of their narrow separation. The bright orange light of the 1st magnitude primary (Antares A) can easily overwhelm the neighbouring mag. 5.4 secondary (Antares B) unless the sky is quite steady during your observation.

You’ll want to use at least 100x magnification to split the pair, and while Antares B is actually blueish-white in colour, it has a reputation for appearing green in contrast to the large red primary star.

5

Zubeneschamali (Beta (β) Librae)

This is the only singleton star in our list. Our other candidates are components in a binary or multiple star system, and it is the juxtaposition of colours that leads to a suggestion of a green tint. But Zubeneschamali manages to take on a green hue all on its own.

Libra is not the easiest constellation to spot in skies that suffer any light pollution. Perhaps the easiest place to start is bright Spica (Alpha (α) Virginis). From Spica, move 27.5° east and north by 1.5°. Zubeneschamali is the second brightest star in Libra, so it should be evident even at a low power.

Beta (β) Librae is a spectral class B8 star that appears pale blue or blue-green at 62x magnification. At 110x it may appear pale green. Step away from the eyepiece for a moment then return, and note your initial impression of the star’s colour.

It is this technique that may produce the most convincing impression of green.

6

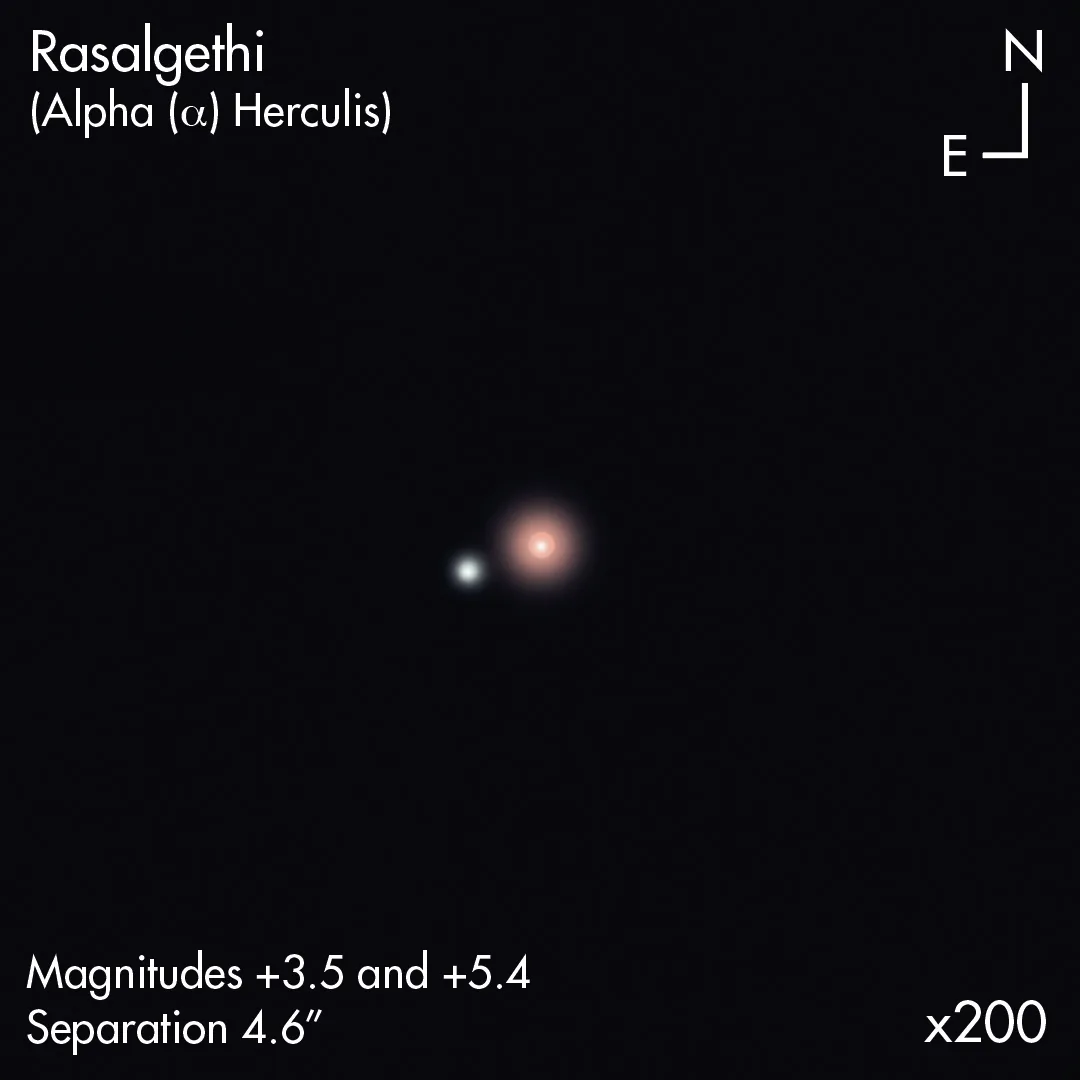

Rasalgethi (Alpha (α) Herculis)

This is another easy pair to see with small telescopes, although tricky to split at only 4.6 arcseconds’ separation.

Rasalgethi is the southernmost star in the eastern leg of Hercules. Find mag. 3.9 Epsilon (ε) Herculis at the southeastern corner of the Keystone of Hercules.

Next, proceed 7° southeast to 3.1 magnitude Delta (δ) Herculis, the eastern knee. From Delta, move 10.5° south to mag. 3.3 Alpha (α) Herculis.

Moderate to good seeing will be required to split the components and discern their colours. Again, both components are the same spectral class (M5), but they appear to be different colours at the eyepiece.

The brighter mag. 3.5 A component appears orange at 62x magnification while the dimmer mag. 5.4 B component appears green or yellowish green at 110x.

7

107 Aquarii

The two stars that comprise 107 Aquarii are the dimmest duo on our list.

But while faint, this dual object is not particularly difficult to find, and is even naked-eye visible in dark skies under good seeing conditions. You’ll need some powerful magnification to spot any hints of green, though.

While located in the region of the sky occupied by Aquarius, the Water Bearer, 107 Aquarii is not actually a part of the constellation, so some star-hopping is required to pin it down.

First, look for mag. 2.1 Diphda (Beta (β) Ceti) in the constellation of Cetus, the Whale. 107 Aquarii lies 13.7° to the west of that. Find a pair of stars that are similar in brightness (mag. 5.6 and mag. 6.5) and separated by just under seven arcseconds.

At lower power, the stars are noticeably different in colour and magnitude, but higher power is needed to tease out any real colour.

The primary is an A9 spectral class star appearing pale creamy yellow at 200x magnification; the B component is type F2 and reveals slightly pale blue tone at 200x. To spot the greenish tint you may need to observe the star at high altitude in a steady sky with higher magnification.

At a glance: our green stars tour

Gamma (γ) Andromedae

- Constellation Andromeda

- Magnitudes +2.32 and +5.02

- Separation 9.4"

- RA 02h03m53.9s

- Dec +42°19'46.6"

Alpha (α) Canum Venaticorum

- Constellation Canes Venatici

- Magnitudes +2.85 and +5.52

- Separation 19.3”

- RA 12h56m01.47s

- Dec +38°19'07.2"

Beta (β) Librae

- Constellation Libra

- Magnitudes +2.62

- Separation NA

- RA 15h17m00.34s

- Dec -09°22'58.7"

Beta (β) Scorpii

- Constellation Scorpius

- Magnitudes +2.59 and +4.52

- Separation 13.7”

- RA 16h05m26.23s

- Dec -19°48'19.9"

Alpha (α) Scorpii

- Constellation Scorpius

- Magnitudes +0.96 and +5.4

- Separation 2.5”

- RA 16h29m24.46s

- Dec -26°25'55.7"

Alpha (α) Herculis

- Constellation Hercules

- Magnitudes +3.48 and +5.4

- Separation 4.64”

- RA 17h14m38.85s

- Dec +14°23'26"

107 Aquarii

- Constellation Aquarius

- Magnitudes +5.65 and +6.46

- Separation 6.7”

- RA 23h46m00.92s.

- Dec -18°40'42"

Have you managed to spot any of the green stars on our list? Let us know by emailing contactus@skyatnightmagazine.com or get in touch via Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

Phyllis Lang is a writer, telescope-maker and owner of the astronomy software company Knightware. This guide originally appeared in the January 2019 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.