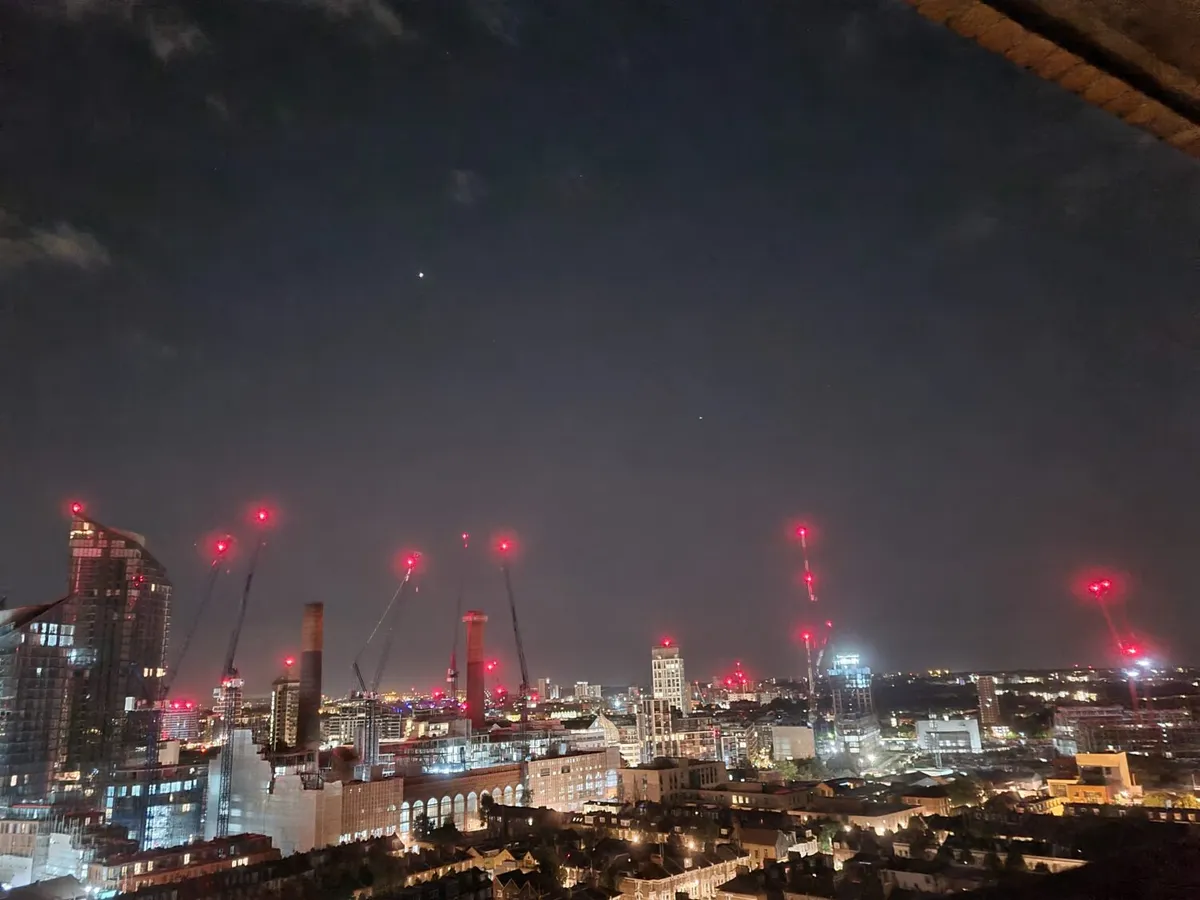

While many stargazers enjoy dark expanses swarming with stars and the Milky Way arcing over remote landscapes, the reality for most of us is that stargazing occurs under, or close to, the bright lights of a town or a city.

From these locations contemplating the Universe can be challenging, as wasted artificial light fills the sky with a diffuse, nocturnal glow known as light pollution.

Although the near-fantastical vistas seen on Instagram and space documentaries might be lightyears from our ‘every night’ experience in a city, there’s still an enormous diversity of engaging targets for an astronomer to enjoy under urban and suburban night skies.

Here we'll explore key examples – and offer some tips on how to get started in stargazing – to show that you don’t need to live under the darkest skies to connect with the wonders of the cosmos above.

For more advice, read our guides on astronomy for beginners, how to stargaze or find out how to do astrophotography from a city.

Understand your city's light pollution

If you live in an urban or suburban area, the fact that badly directed and excessive artificial light obscures the stars over our towns and cities isn’t going to be news to you.

But if you’re just getting into stargazing, it can be useful to explore exactly how this light pollution affects certain kinds of astronomical observing, not least because this can help you prepare for nights when the effects are lessened somewhat.

Clouds, of course, can spoil an observing session no matter where you’re observing - and you can mitigate this somewhat by learning how to predict the weather for stargazing - but there’s another atmospheric phenomenon that all town-based stargazers will know is important to the clarity of their views. Astronomers call it the ‘transparency’.

Atmospheric transparency is a measure of how clear your clear skies are.

Hazes or pollution (suspended in the air) can create milky, murky skies and what can be called ‘poor’ transparency. Conversely, crystal-clear nights free of these intrusions are said to possess ‘good’ transparency.

The reason why transparency is important to monitor when observing the night sky from urban areas is that hazy skies can elevate the problems associated with light pollution.

The particles in the air scatter the glow from below and the result is a brighter night sky, where it’s harder to see fainter stars.

Paying attention to transparency levels can help you plan observing sessions.

If you can see that the sky is milky and the skyglow is enhanced you can focus your attention on brighter targets like observing the Moon and observing the planets.

When the transparency is good you can go after fainter objects like star clusters.

Find out how clear your skies are

When you begin exploring the night sky from a town or city it’s a great idea to have a star atlas, a planetarium computer program or a stargazing app to help you navigate your way around the stars.

However, before you open one of these up, it’s well worth doing a quick exercise to establish what you can actually see under your local night sky.

Essentially, you want to find out what the faintest stars are that you can discern – what astronomers call the ‘naked-eye limiting magnitude’ or NELM.

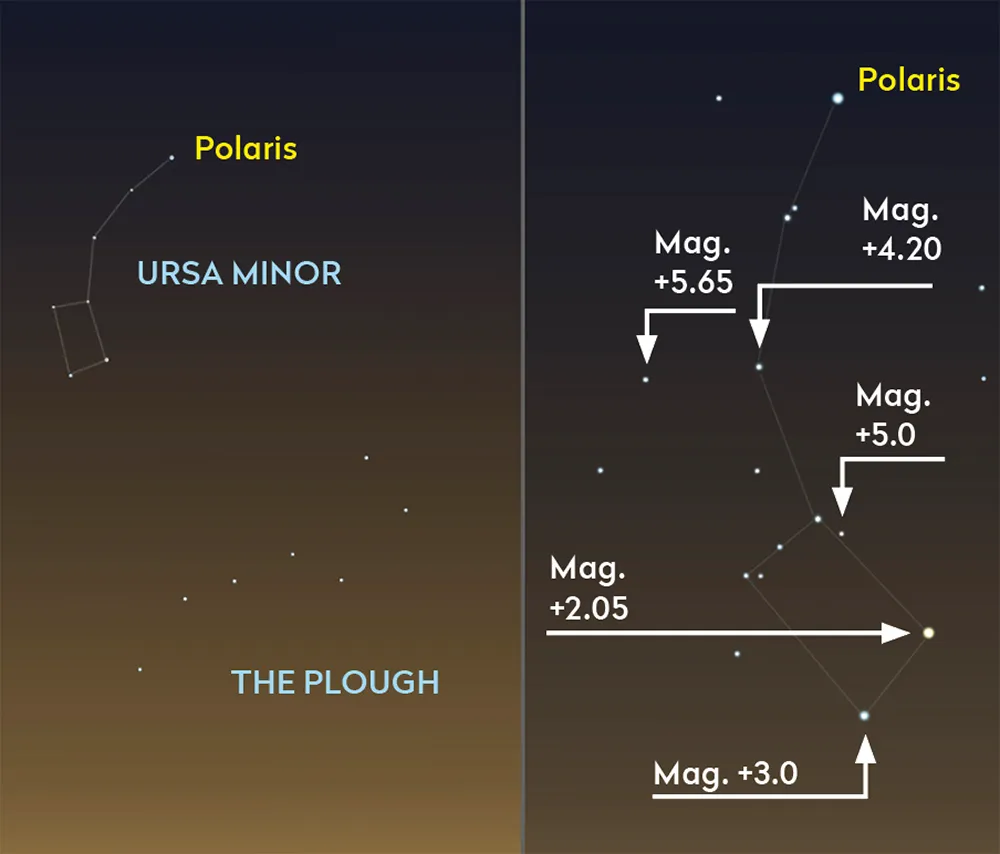

To do this you can use a constellation that’s always visible at night in the UK, like Ursa Minor, the Little Bear.

It’s a fairly easy pattern to find as the tip of the Little Bear’s tail is the bright star Polaris, the North Star.

Using the chart here (right), a star chart or an app, look carefully to see what brightness, or magnitude, the dimmest star you can perceive is – remember, the lower the number, the brighter the star.

For suburban locations under fairly average conditions, this might be around mag. 3.0 to 4.0.

Many planetarium programs and apps have tools that have the ability to limit the magnitude of the stars displayed.

So if you set the magnitude at the level of your local NELM, what’s shown on screen will be only the stars you can see from your observing site.

In turn, this can make star-hopping, or jumping from star to star to locate fainter objects, much easier.

Using a telescope from a light-polluted city

While many fainter objects will be largely lost or hard to find in the skyglow from suburban locations, a small telescope or a good pair of binoculars will nonetheless show you a respectable number of brighter deep-sky targets including star clusters, bright planetary nebulae and summer and winter showpieces like the Orion Nebula and the Lagoon Nebula.

There are also a few things you can do to reveal these wonders more clearly from a city.

Firstly, use a light pollutionfilter tailored to visual observing, as these are specifically designed to suppress the glow from artificial light.

Consider your observing position, too. For example, never observe from inside a building with the door or window open, as the escaping warm air will create air currents and cause the view to shimmer.

This is most noticeable when viewing the Moon and planets, but applies to deep-sky astronomy too.

Try not to view targets that are directly over rooftops or above hot air vents, as that will avoid similar issues.

Finally, just as one would from a darker location, allow your eyes at least 30 minutes to adapt to what darkness there is – and keep any artificial lights out of your direct line of sight if you can.

Observing the planets from a city

The planets are one of the few astronomical target groups that are pretty much completely unaffected by the problems of light pollution.

While you’ll probably struggle to glimpse distant Uranus with the naked eye, like you can at dark-sky sites, and telescopic observations of some of the fainter moons of Saturn might be a little harder to come by, for the most part you can get great views of the other planets of the Solar System with a small telescope even from brightly-lit cities.

What’s more, high-resolution planetary imaging can be conducted with great success under light-polluted skies – some of the world’s best astrophotographers in this field work from homes in urban and suburban locations.

Jupiter with its cloud bands and Saturn with its rings are of course superb targets for even small-aperture instruments.

Bright Mars at opposition and the crescent Venus also offer captivating views in larger aperture scopes – the latter needing a careful observing approach, ensuring the Sun is below the horizon before viewing starts.

From suburban locations, with a 200–250mm aperture telescope, you can even get nice eyepiece views of the faint discs of Uranus and Neptune.

Observing the stars from a city

Among the stars that are able to poke through the light pollution in built-up areas you’ll find some interesting targets for a small to medium aperture telescope.

These include some of the brighter double and multiple-star systems, where two or more stars either appear close together or are, in fact, whirling together as a gravitationally-bound group through space.

In the summer and autumn months, notable examples such as Albireo (Beta (β) Cygni) in Cygnus, and Epsilon (ε) Lyrae in Lyra, are comfortably within reach of a 150–200mm aperture telescope from sites with fairly bright night skies.

If you’re interested in long-term observing projects with a telescope, you’ll also find that some variable stars – stars whose brightness fluctuates – like Algol (Beta (β) Persei) in Perseus, often periodically glow strongly enough to be seen through moderate light pollution.

Observing them and recording estimates of their magnitudes can be an interesting and rewarding exercise.

If you’re keen, you can even get involved with the scientific work of organisations such as the British Astronomical Association and the American Association of Variable Star Observers by submitting measurements to their variable star monitoring programs.

Observing noctilucent clouds from a city

During summer in the UK, noctilucent – meaning ‘night-shining’ – clouds can appear on the northern horizon about an hour and a half after the Sun has set.

Composed of ice crystals, noctilucent clouds form around 85km up in our atmosphere and shine because, at those heights, they’re in sunlight.

The brightest displays can be easily seen and photographed from light-polluted towns and cities against the twilight.

Noctilucent clouds, or NLCs, have a characteristic blueish-white hue to them and so stand out quite clearly from regular high clouds, like cirrus, from urban spots.

This is because when cirrus is being lit by light pollution it will usually have a slight orangey or greenish-white hue.

Wisps of regular high cloud also tend to look quite dull when scattering skyglow, whereas bright NLCs really do look like they’re glowing.

This guide originally appeared in the October 2021 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.