The main building of the historic Lick Observatory, with the dome hosting the 36-inch Great Refractor open. Image Credit: UC Regents / Lick Observatory (Jonathan Chang)

During 2017 we journeyed to the Californian hills to capture the cosmos through the 129-year-old Great Refractor at the Lick Observatory, 120km south of San Francisco.

Our goal?

To point this historic telescope towards some of our favourite targets and capture its antique observing power through the eyes of a modern DSLR camera.

A contact at the University of California, Santa Cruz put us in touch with the Lick Observatory staff, and once we explained the nature of our project, they too were intrigued at the prospect of using this mighty telescope to capture deep-sky images with a contemporary camera.

We quickly learned that the cost to operate the 19th century relic would be significant, so we launched an overwhelmingly successful Kickstarter project to fund this astronomical madness.

We were able to make four, three-hour trips to the observatory during the year, and much planning was required to ensure we could capture quality astro images while allowing for the steep learning curve of getting to know our way around the historic instrument.

The Lick Observatory was the brainchild of James Lick, born in Stumpstown (now Fredericksburg) Pennsylvania, on 25 August 1796.

After making his fortune in the housing boom of San Francisco, spurred on by the California Gold Rush of the mid-1800s, Lick decided to spend his money building one of the largest telescopes of the era, in the world’s first mountaintop observatory.

Classic, elegant craftsmanship

When navigating the narrow trail to reach the observatory today, you get a feel for how tough its construction must have been.

The steep road up Mount Hamilton climbs into California’s Diablo Range just east of San José, and although it’s only about 40km from the base of the mountain, it takes roughly an hour to traverse the windy mountain trail.

However, the route provides some amazing views of the Santa Clara Valley along the way.

The Great Lick Refractor is something we were both already familiar with, having visited the telescope in the past and taken a tour of the observatory.

We were mesmerised by its history and the craftsmanship behind its construction: particularly the fact that the instrument is 17m long with a whopping 1m aperture!

Looking through a regular 2-inch eyepiece at the end of the Great Lick Refractor is a real treat, but we were excited to have the opportunity replace that eyepiece with our Canon EOS 6D DSLR camera to see how well the two would combine to image the night sky.

The telescope tube is so long that, in order to view objects near the horizon, the entire observatory floor has to be hydraulically raised so you can access the eyepiece.

Its antique controls, oversized gauges and brass finishing make you feel like you’re aboard one of Jules Verne’s extraordinary craft.

Adding to this illusion are the hand wheels on the main telescope focus and the mount controls that were built by the 19th century US manufacturers Warner & Swasey Co, both of which resemble steering wheels on old vessels.

You can easily drop a regular eyepiece into the 11,400kg telescope, and while the 129-year-old lens has its imperfections, its light-capturing power can still leave observers in awe.

Tricky tracking

Imaging with the Great Lick Refractor using a modern day DSLR camera proved to be a rewarding feat.

While the tracking isn’t as good as many consumer telescopes available today, this doesn’t really matter because the power of the lens provides plenty of photons, even with short exposures of 20 to 30 seconds.

The lens does suffer from some chromatic aberrations, which means that it bends the red and blue wavelengths of the light spectrum slightly out of sync, causing them to look a bit blurry.

But frankly, this is a trivial problem in the grand scheme of things.

After all, standing in the grounds of this historic building, observing ancient light from distant galaxies through a titanic 129-year-old refractor and capturing them on a digital camera is enough to make anyone marvel at the prowess of human endeavour, and the wonders of the Universe around us.

From gold rush to galaxies

James Lick was the son of a carpenter who followed his father’s trade, eventually becoming a master piano maker.

In 1848, Lick made his way to the small village of San Francisco and began buying real estate.

Shortly thereafter, gold was found near Sutter’s Mill and the California Gold Rush began.

While Lick did try his luck in the gold mines, he decided that real estate was a more suitable calling.

The housing boom that followed the Gold Rush made him the wealthiest man in California.

As he was always interested in science, especially astronomy, in 1875 he donated $700,000 to build an observatory atop 1,300m Mount Hamilton and equip it with the largest, most powerful telescope on the planet.

This would prove to be an engineering feat of monumental proportions, as first a hand-built road had to be constructed up the rugged mountain.

Then, piece-by-piece, the telescope components were trekked up the mountain by horse and carriage.

Troubleshooting with the telescope and massive lens had to be done on-site, which proved to be difficult given the limited accessibility and cold temperatures.

Construction took place from 1880 to 1888, but Lick had already passed away in October 1876 before work had even begun.

The great telescope builder was buried in a tomb at the base of the mammoth instrument, where he lies today, a brass plaque bearing the simple inscription, “Here lies the body of James Lick”.

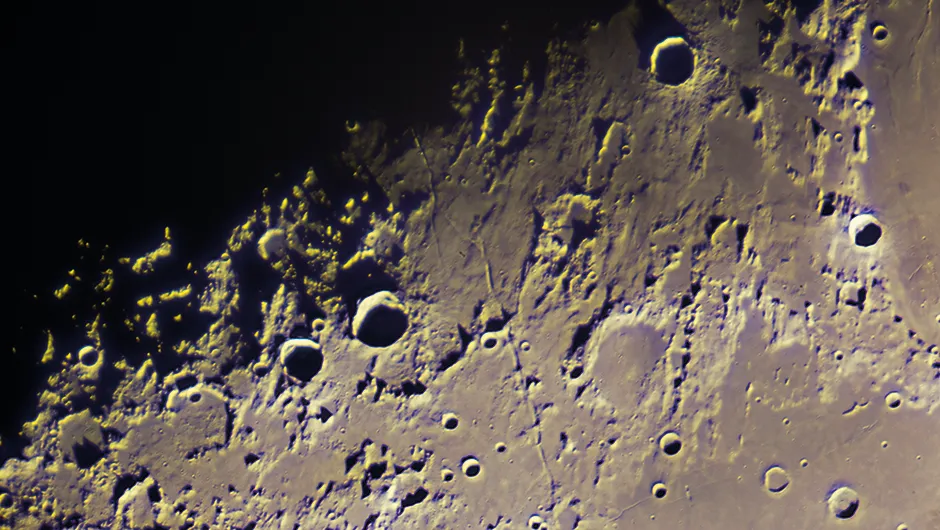

Below is a selection of images taken by Scott and Nick at the Lick Observatory.

The refractor’s tracking abilities limit exposures to around 30 seconds – which restricts light collection – but its huge 1m aperture more than compensates.

Scott Lange and Nick Foster are astro imagers who travel the world looking for astronomy adventures.