When the Mars Exploration Rover (MER) Opportunity trundled to the edge of Endeavour Crater back in August, it was the end of a three-year journey from its last major destination, Victoria Crater.

The fact that the distance between the two craters is 21km shows how carefully Opportunity takes it.But, as the scientists and engineers on the MER say, when you’re an average of 225 million km from home you want to take it slowly, partly not to miss anything interesting and partly to avoid hazards.

Despite the stately pace, Opportunity’s sister rover Spirit didn’t quite manage this – it became stuck in dusty soil in May 2009.Communications officially ended two years later, in May 2011, when its batteries finally drained.

Anyway, when Opportunity reached the edge of Endeavour Crater last month, it sent back some fantastic panoramas of the view over the 22km diameter crater, like these:

It’s striking how well these convey a sense of distance.To human eyes the range of hills that marks the opposite side of the crater from Opportunity is clearly some distance away.

There’s a term for the visual cues that we instinctively use to tell us how far away elements of a landscape are – psychologists call it aerial perspective.

As University of Stirling psychologist Dr Helen Ross explains, “We use cues from the atmosphere to judge distance. This is known as 'aerial perspective'.

“The reduction in brightness and colour contrast of distant objects acts as a perceptual cue to distance, analogous to linear perspective.

“We can make big mistakes on Earth when the atmosphere is unusually clear or misty.

In a dry desert, distances look much closer than they are; and in a mist they look too far.”

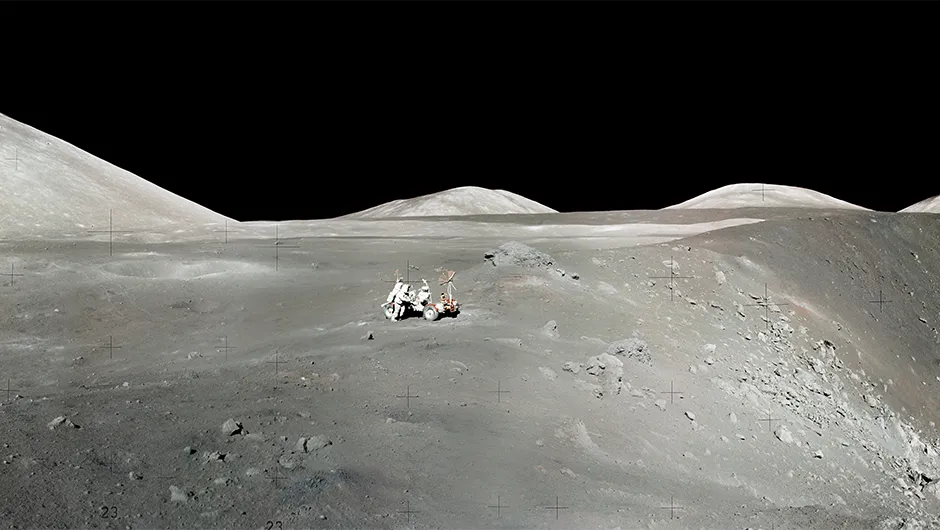

To see just how much we rely on the atmospheric cues, take a look at this image, taken in the Taurus-Littrow Valley on the first moonwalk of the Apollo 17 mission.

Cameraman Harrison Schmidt has snapped Eugene Cernan kneeling to extract a deep core from the lunar valley floor.

Beyond him and slightly to the right rises the Sculptured Hills, partly in shadow.

But, from this image, it’s very difficult to appreciate that the Sculptured Hills are almost 2,000m above the ground on which the two astronauts are standing.

That’s higher than Ben Nevis, the highest peak in the British Isles at 1,350m, and would make the Sculptured Hills a medium-sized peak in the Alps.

Imaged in the Moon’s atmosphere-free environment, this lofty peak appears to be a gently rising hill.

They may have been sent to us robotically, but the views on Mars are certainly more like home than our nearest neighbour.