Have you ever wondered how big the Moon's features are compared with some of the most famous features on Earth?

How do the Moon's craters, its mountains and lunar maria measure up with features, countries and buildings on Earth?

The Moon looks great through a telescope, but at over 380,000km away it's hard to get a sense of how big its standout features really are.

Here, we take a look at some of the standout lunar phenomena and how they size-up when put alongside some of Earth's familiar natural sights.

For help making the most of our natural satellite, read our guide on how to observe the Moon and the best features to observe on the Moon.

The Moon vs the UK and Ireland

The Moon’s diameter is 3,475km, roughly a quarter of Earth’s.

The straight-line distance between Land’s End in England and John o’ Groats in Scotland is 960km, roughly a quarter of the Moon’s diameter.

From Earth, the Moon has an apparent diameter that varies between 33.6 and 29.4 arcseconds, with a mean value of 31.1 arcseconds.

For simplicity’s sake, the Moon’s apparent diameter is normally described as being half a degree.

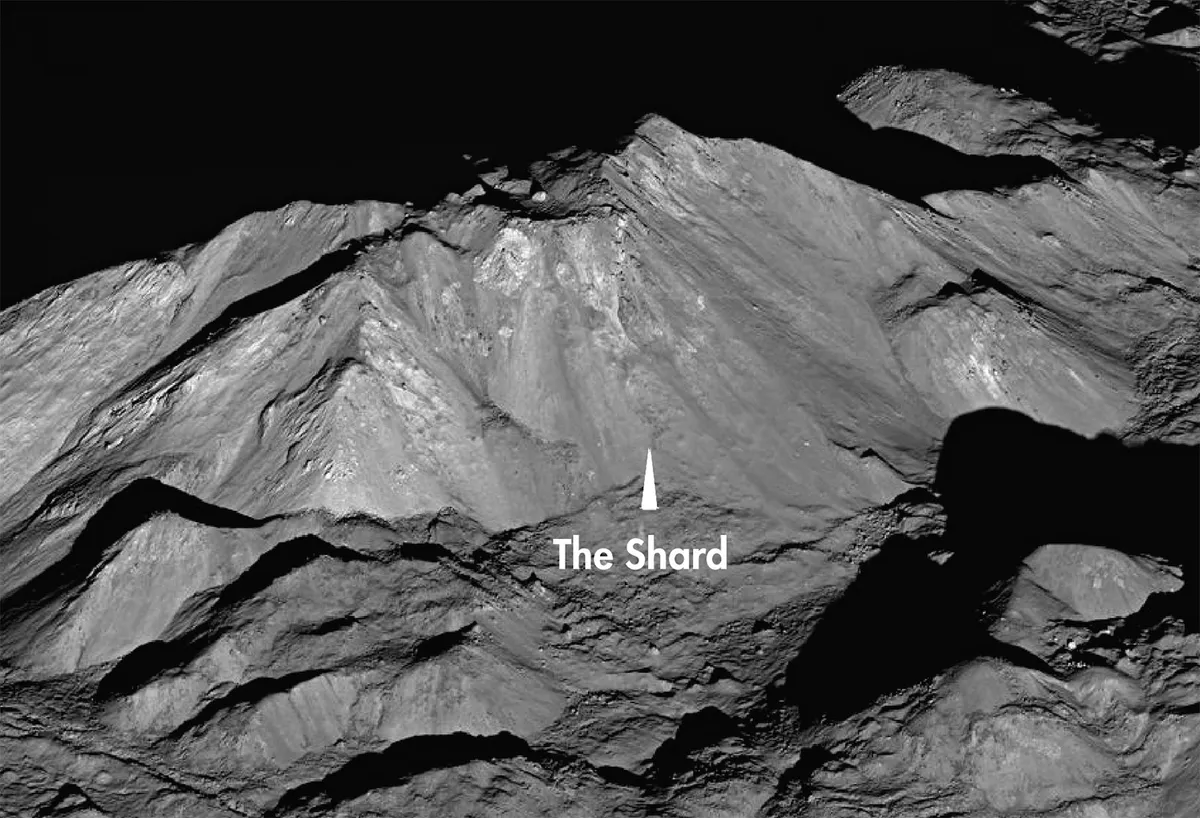

Crater Tycho vs London's Shard

The southern ray crater Tycho has a distinctive rim measuring 88km across, similar to the distance from central London to Oxford.

The 60km diameter M25 around London would just fit across Tycho’s inner floor.

The crater has a 2,000m high central peak, roughly 6.5 times the height of the 310m-tall London Shard.

The peak is easily visible with a small telescope.

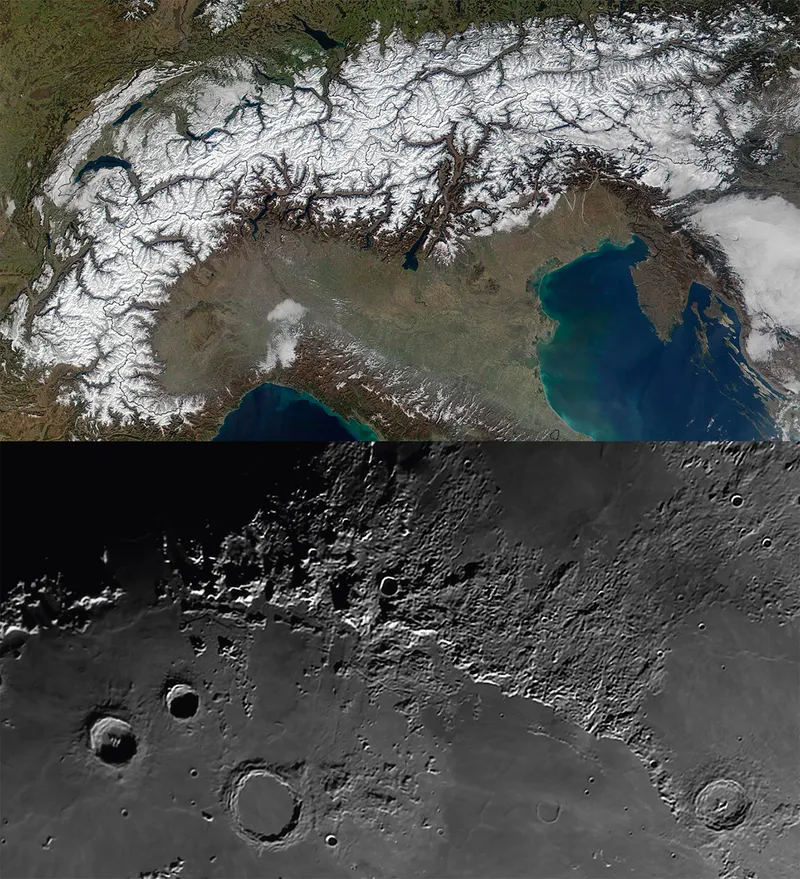

Lunar Apennines vs the Alps

The lunar Apennine mountains define the southeast border of the Mare Imbrium.

The range is 600km long, containing peaks that rise to over 5km.

The Alps on Earth are 1.5 times longer at 960km, with the highest peak – Mont Blanc – rising to 4.8km.

The Apennines were formed when material was pushed aside by the impact that formed the Imbrium Basin.

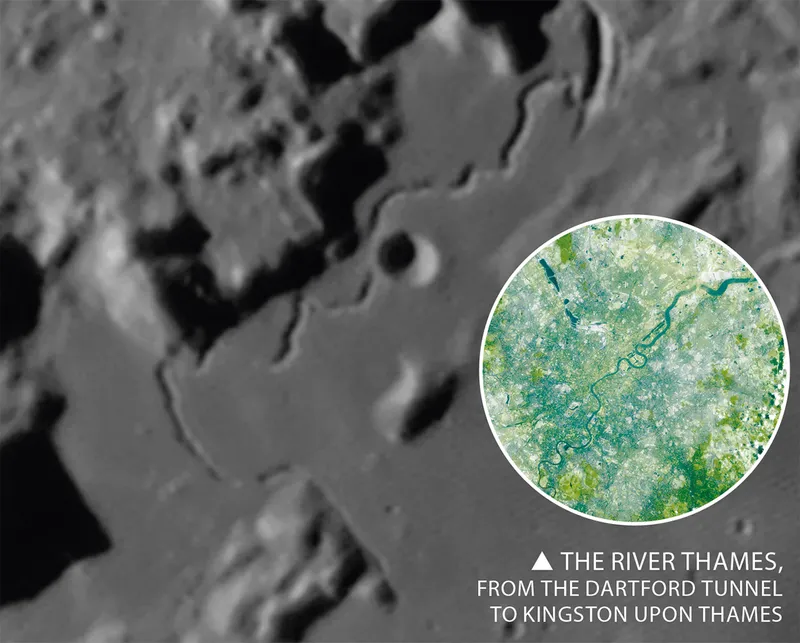

Hadley Rille vs the River Thames

Hadley Rille is a crack in the lunar surface formed when the ceiling of an ancient, submerged river of lava collapsed.

Requiring at least an 8-inch scope to see, its main part is 80km long, with a maximum width of 2,000m and depth of 370m.

By comparison, England’s River Thames is 346km long in total, and 252m wide when passing the Houses of Parliament.

In its estuary, its depth is 20m at most.

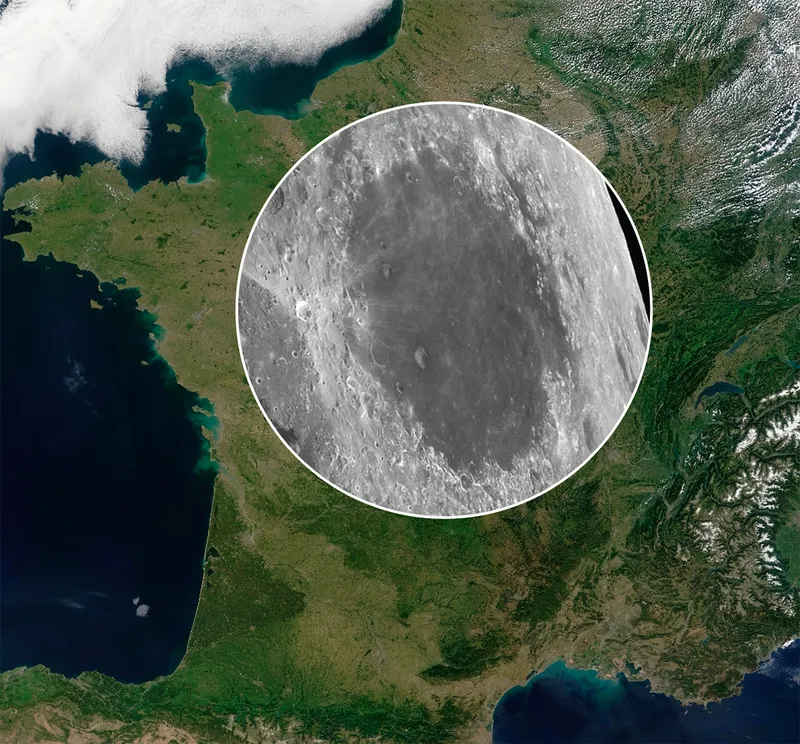

Mare Crisium vs France

The Mare Crisium is a dark, oval feature seen close to the Moon’s northeastern edge.

Its 400km x 530km floor is the result of an impact with a 25km-wide body about 3.9 billion years ago.

The whole of Ireland would fit inside it, while the Mare Crisium itself would in turn fit comfortably inside France.

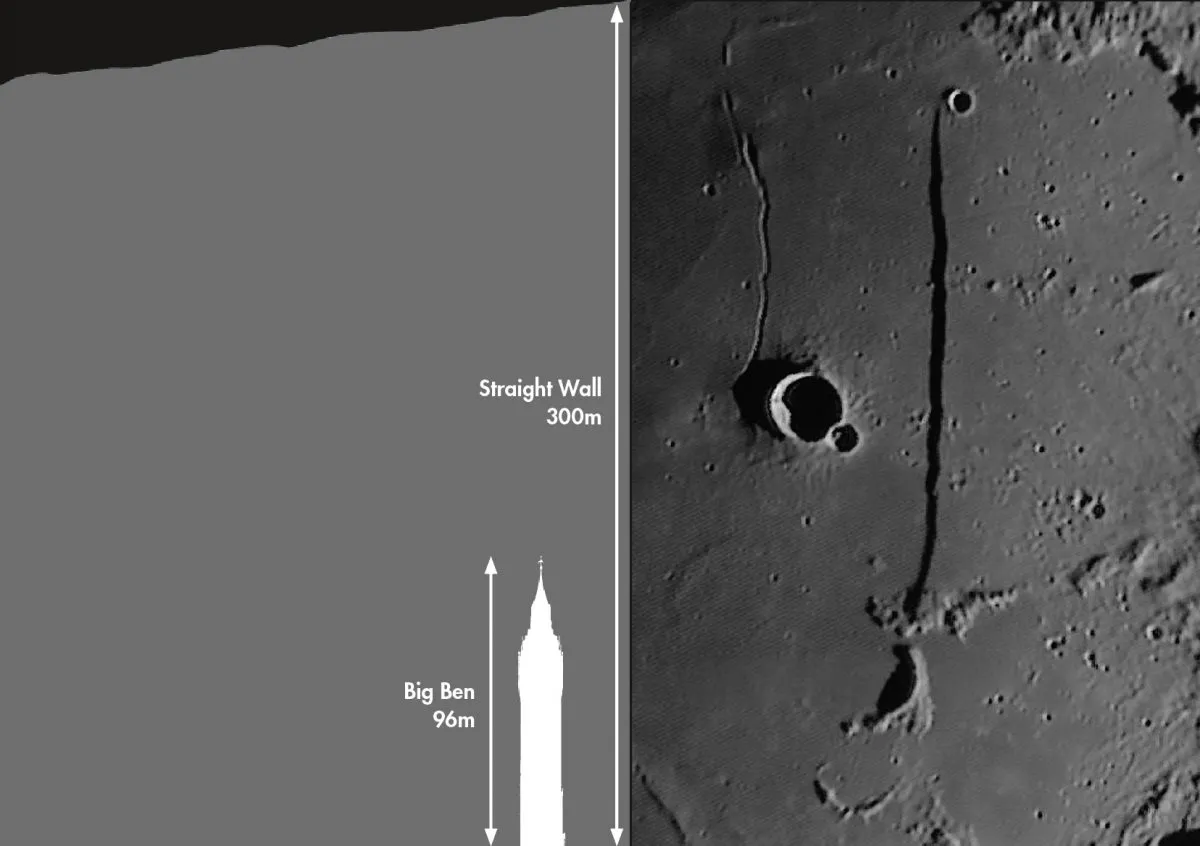

The Straight Wall vs Big Ben

The Straight Wall, or Rupes Recta, is a 110km linear fault.

Seen a day after first quarter its shadow gives the impression of a sheer cliff, but its 300m height difference is actually achieved by a gentle 7° slope.

The fault’s height is roughly three times that of Big Ben’s tower.

Crater Copernicus vs the Midlands

Crater Copernicus is a ray crater to the south of the Imbrium Basin.

Its 93km-diameter rim contains a central mountain peak complex rising to 1,200m – four times the height of the London Shard.

If Crater Copernicus was centred on Birmingham, the rim would reach out almost as far as Leicester, while the longest ejecta rays would reach all the way to Orkney.

How the Moon's mountains compare to Earth's

There are many dramatic mountains on the Moon.

Large impact craters have central peaks that formed when impact-heated material flowed back into the crater’s centre, rising and cooling to form mountains.

The lunar seas resulted from larger impacts, which caused material to be compressed up into enormous mountain ranges at their edge.

As the impact basin filled with lava, entire ranges were sometimes engulfed, leaving a few solitary peaks poking out.

Here’s how some of the biggest stack up next to Earth’s highest mountain, Mount Everest, which is 8.8km high.

Mons Huygens

Height: 5.4km high

Mons Huygens is located within the southern Apennines. At its highest, the peak rises to an altitude

of 5.4km, and from north to south it measures 50km.

Mons Hadley

Height: 4.8km high

Mons Hadley lies in the northern Apennines, just to the northeast of Hadley Rille, and at 4.8km is the highest peak in this region. It overlooks the Apollo 15 landing site (more on this in our guide to seeing the Apollo landing sites)

Mons Pico

Height: 2.4km high

Mons Pico is an isolated peak in the Imbrium Basin. Located 180km to the south of Crater Plato, Pico rises 2.4km and casts an impressive pointed shadow at first quarter.

Mons Piton

Height: 2.25km high

Mons Piton is another isolated peak in the Imbrium Basin, lying roughly 130km west of Crater Cassini. It rises 2.25km above the basin floor and is best seen at first quarter.

This article originally appeared in the September 2012 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.