Astronomy is known as an exact science, yet its history is a weird mix of pre-scientific mythology, early ignorance and outright misunderstanding. As a result, today’s astronomers – and the general public at large – use a wide variety of illogical terms, erratic names and confusing labels for the objects of their study.

Although we know better by now, most of these misguided descriptions are probably here to stay.

Here are 12 examples of astronomical parlance gone astray. If you know of any others, let us know! Get in touch via contactus@skyatnightmagazine.com.

For more astronomy lists, read our 17 facts about astronomy and space, 10 greatest comets of recent times, 9 mind-blowing facts about the Universe, and our guide to the weirdest stars in the Universe.

1

Milky Way

Ever wondered how the Milky Way got its name? Astronomers have found the spectroscopic fingerprint of alcohol molecules in space, but milk? – forget it.

Even the word ‘galaxy’ is derived from the Greek and Latin words for milk (as is ‘lactose’).

Moreover, the association between the faint band of starlight and the white mammalian liquid can be found in many languages around Europe: Milchstrasse in German, Voie lactée in French, Melkweg in Dutch, Melkevein in Norwegian. So what’s going on?

Maybe Greek mythology is to blame. According to the ancient Greeks, when Zeus’s wife Hera was breastfeeding Heracles (known as Hercules by the Romans), the muscular infant was suckling so greedily that mother milk got spilled all across the velvet-black sky.

However, given the fact that the same name is being used in so many languages, its origin may be much older.

Today, we know that the Milky Way is just the projection of our home galaxy on the sky, as seen from our vantage point at the edge of one of the spiral arms.

Less than a century ago, astronomers discovered that other ‘spiral nebulae’ are galaxies in their own right. Next time you read about intergalactic space, or about active galactic nuclei, spare a thought for little Heracles.

Did you know that the Milky Way is predicted to collide with its cosmic neighbour the Andromeda Galaxy in the future? Find out more in our guide to the Andromeda-Milky Way collision.

2

Shooting star

Yes, it looks like a star that’s falling from the sky. Luckily, distant suns do not crash onto our tiny planet.

The streaks of light that can be seen at any clear night are caused by tiny grains and pebbles that enter the Earth’s atmosphere at over 10 kilometres per second.

As a result, air molecules are heated up and start to glow. Officially, a shooting star is known as a meteor, underlining the link to the atmosphere (think ‘meteorology’).

Find our more about shooting stars and how to see them with our beginner's guide to meteor showers.

3

Nuclear burning

Clever kids often ask: ‘If there’s no oxygen in space, how can stars burn?’ Indeed, the chemical process known as ‘burning’ needs oxygen, as evidenced by candle extinguishers.

Still, all stars in the universe give off light and heat, just like a giant fire. In the 1930s, physicists discovered the energy source of the stars: nuclei of light elements like hydrogen are fused into heavier ones.

Energy is released as a by-product. Too often, this is wrongly called ‘nuclear burning’ or ‘hydrogen burning’.

But the clever kids are right. Nucleosynthesis (referring to the production of new elements) is a much better term.

For more info, read our beginner's guide to stars.

4

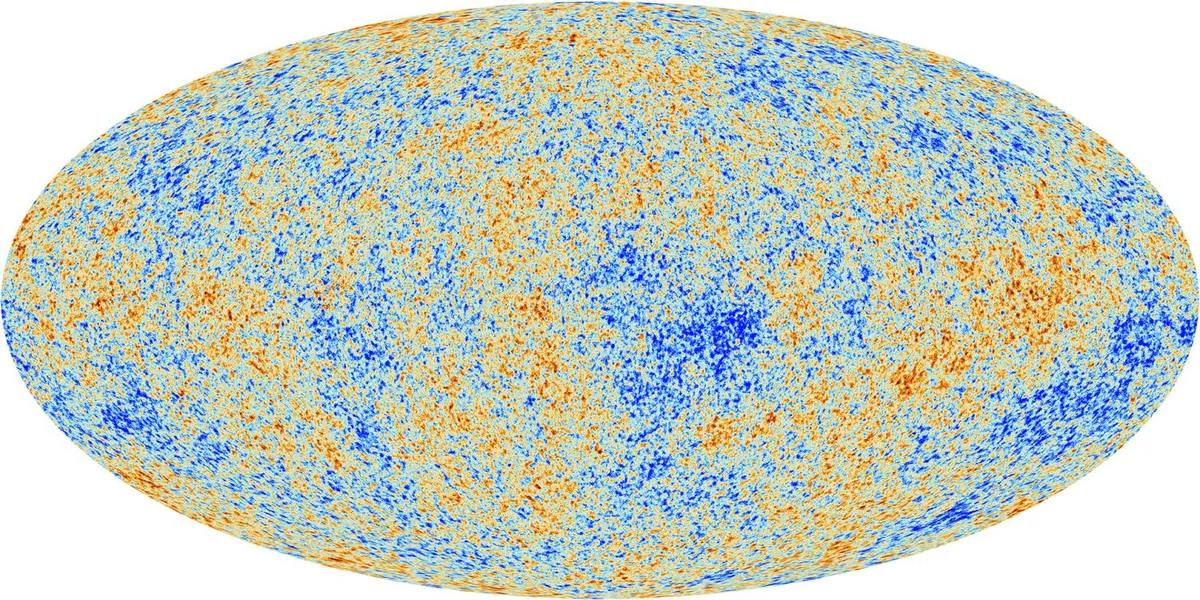

Big bang

In space, no one can hear you scream. Even the explosive origin of the universe was a quiet affair, as far as audible sound goes.

The name ‘big bang’ was coined in 1949 on BBC radio as a derogative term by Fred Hoyle, who didn’t believe in the theory. It stuck.

Although astronomers know there was no real ‘bang’, no one ever came up with a viable alternative. Incidentally, there were ‘acoustic oscillations’ in the early Universe, but that’s another story.

5

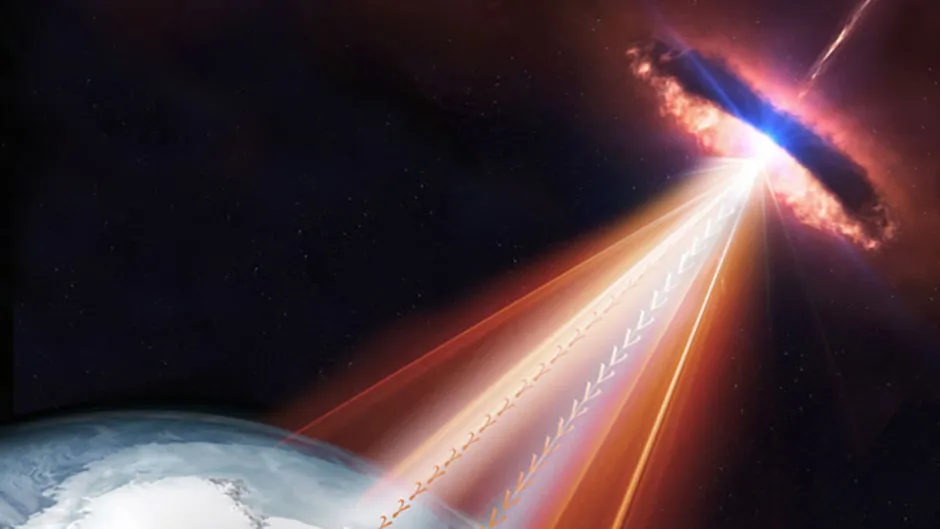

Cosmic rays

In 1895, German physicist Wilhelm Röntgen discovered invisible, energetic radiation that he labelled ‘X-rays’ (as in ‘unknown’).

When his Austrian colleague Victor Hess, in 1912, found a similarly ionizing agent coming from outer space, the name ‘cosmic rays’ seemed appropriate.

However, by the late 1920s it became clear that this is not electromagnetic radiation at all (like X-rays or gamma rays), but a cosmic buckshot of energetic particles, mostly electrons and protons, accelerated in supernova shocks and other explosive events.

The erroneous label was never replaced. As a result, astrophysicists now even use the paradoxical term ‘cosmic ray particles’.

6

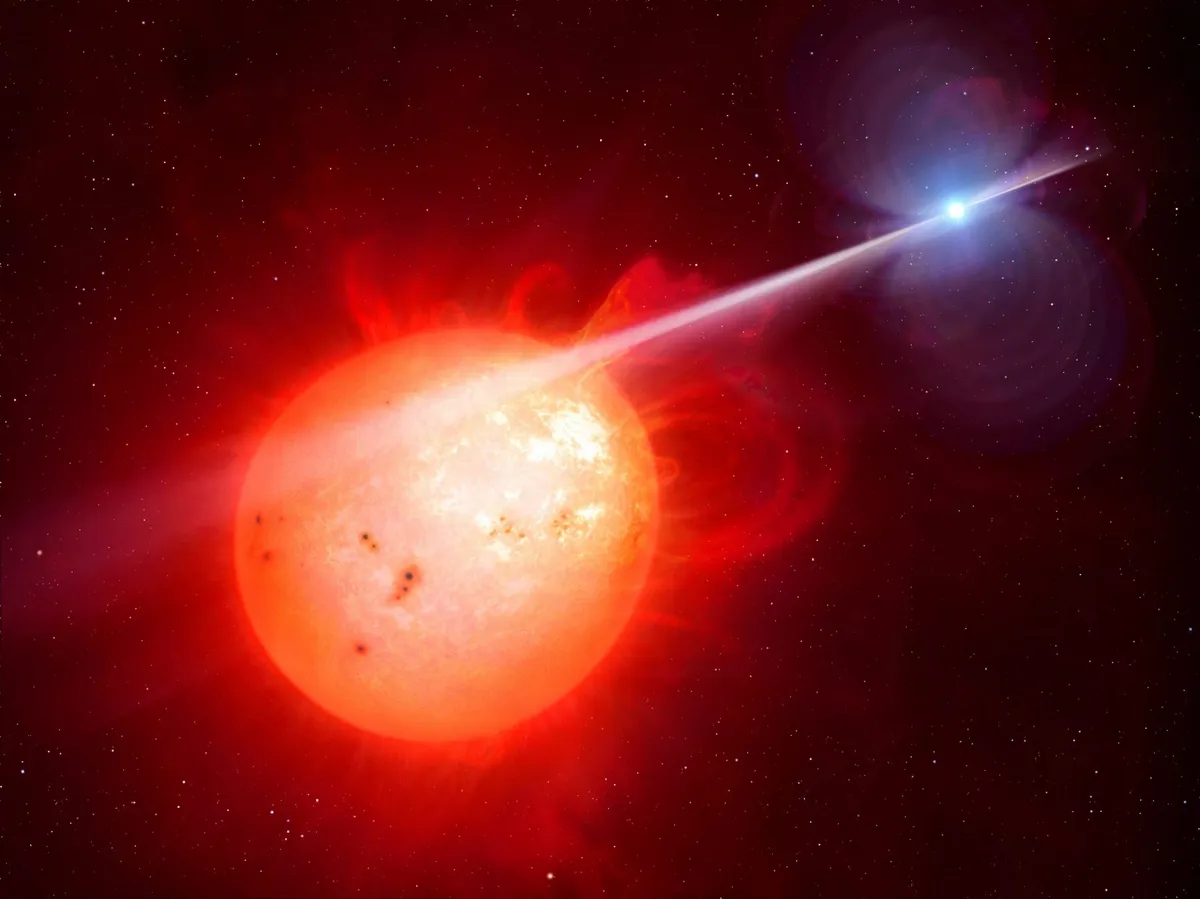

Dwarf star

Giants are huge; dwarfs are tiny. Not in astrophysics, though. In scientific parlance, every star that is converting hydrogen into helium in its core is known as a dwarf star.

So yes, red dwarfs are dwarf stars, but so is our own Sun. Even more remarkable, the hottest dwarf stars in the universe can be more than 20 times more massive and 20,000 times more luminous than the Sun!

No sensible person would ever call such a monstrous star a dwarf, but astronomers do.

7

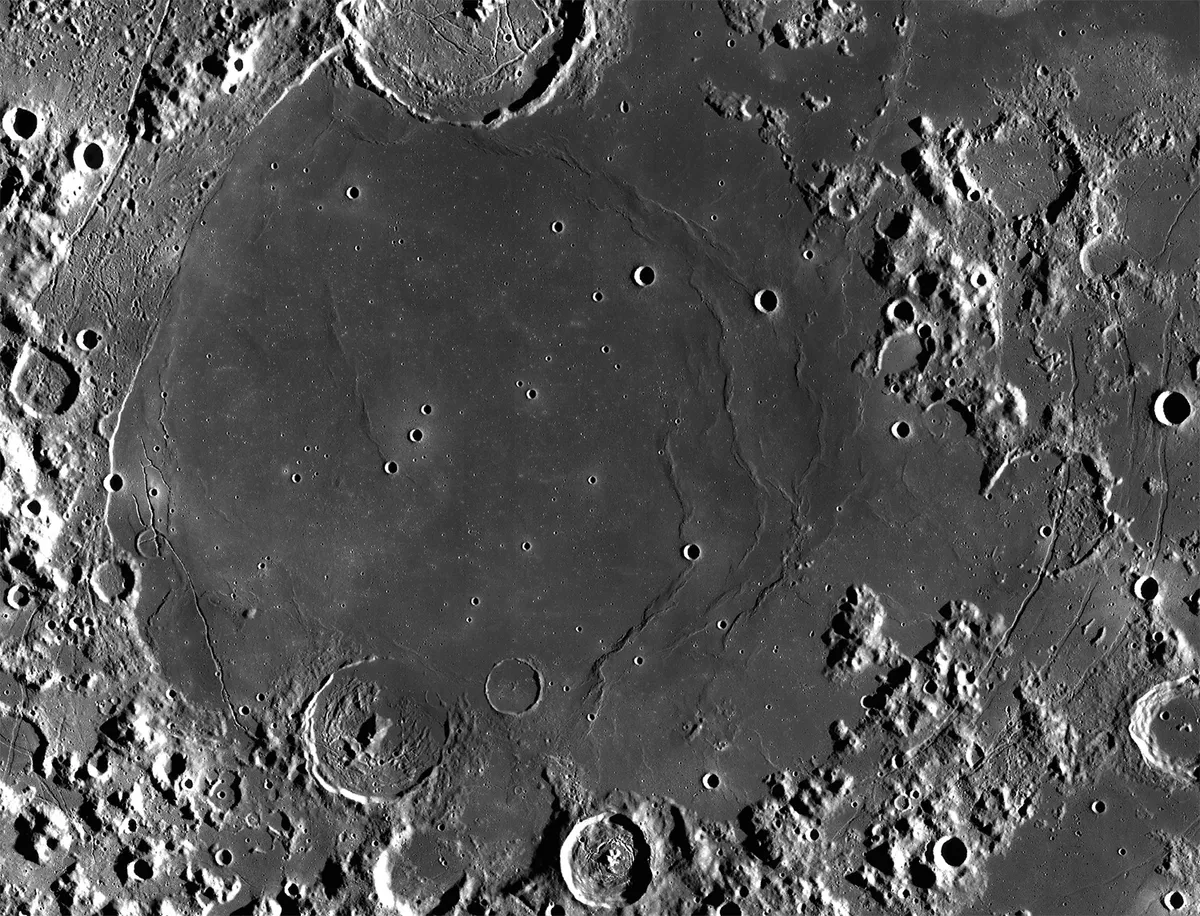

Lunar seas

"Tranquillity Base here, the Eagle has landed."Just over half a century ago, Neil Armstrong was the first human being to set foot on the Moon during Apollo 11.

Tranquillity Base was named after Mare Tranquillitatis (the Sea of Tranquillity), on which Apollo 11 made its historic descent. But wait… seas on the Moon? The Eagle wasn’t a barque, right?

Indeed, the Moon is bone-dry. Because there’s no atmosphere, any surface water would immediately evaporate into space.

But 400 years ago, when astronomers first studied our nearest celestial neighbour through their first simple telescopes, it was generally assumed that the dark areas on the moon were water – the so-called lunar seas, or lunar maria (plural of the Latin word for sea, ‘mare’).

The brighter parts of the Moon were thought to be the lunar mainland. The first maps of the Moon even carried now-obsolete names like Terra Dignitatis and Terra Caloris.

Apart from maria, the Moon has one ocean (Oceanus Procellarum), a number of lakes (including Lacus Mortis), a few marshes (palus in Latin), and bays (the most famous of which is Rainbow Bay, or Sinus Iridum.

Beautiful names, but plain wrong. Incidentally, dark areas on the planet Mars are also known as seas.

8

Metals

You’re breathing metals. No kidding: nitrogen and oxygen, the two main constituents of the air you breathe, are known to astronomers as metals.

Just like every single chemical element except hydrogen and helium, which were forged in the big bang.

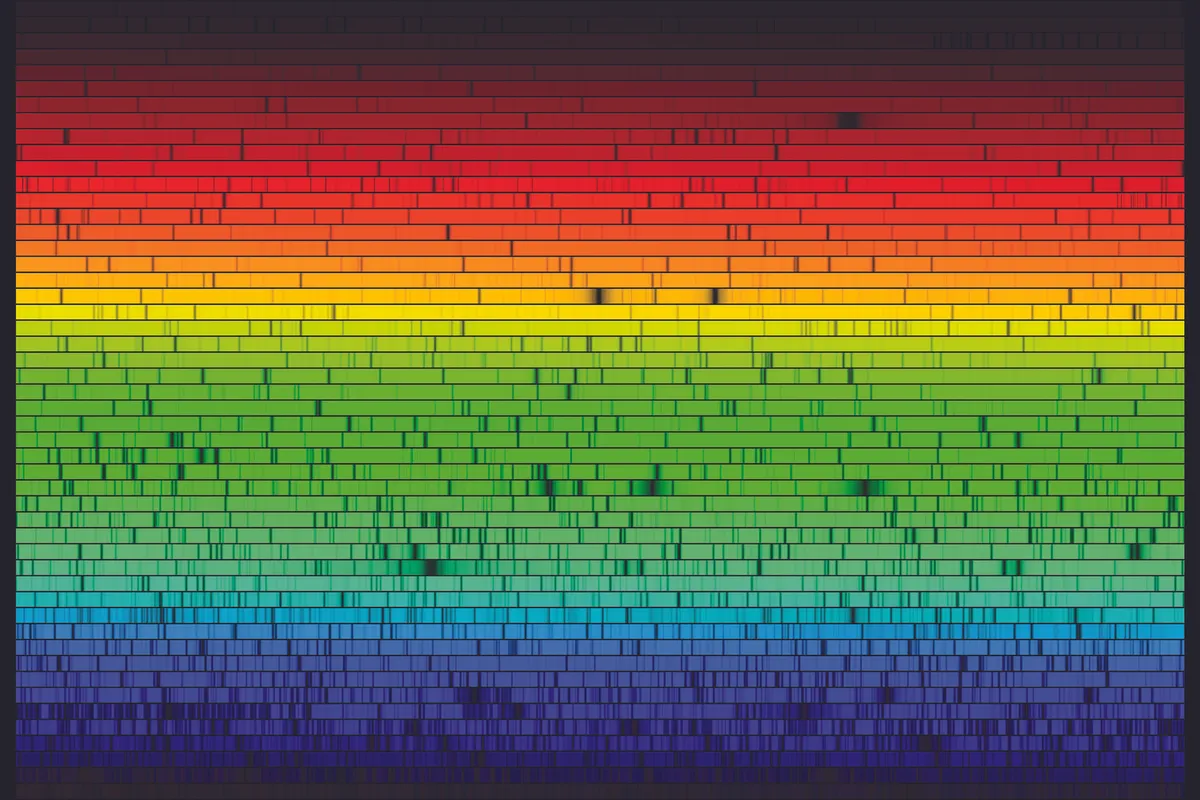

In the early days of spectroscopy, ‘real’ metals like sodium, magnesium and iron, were discovered first, because their spectroscopic fingerprints are more obvious.

Later, when lighter elements were also found, they simply received the same label.

Silly, but useful: the metallicity of a star (usually a few percent) is now a handy measure of the amount of non-big bang elements it contains.

For more info, read our guide to the science of spectroscopy.

9

Asteroids

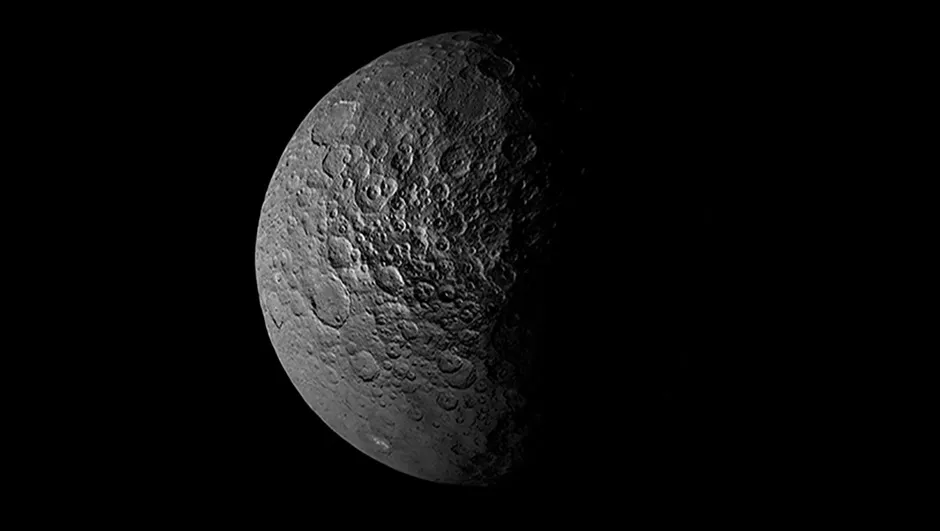

Ceres (pictured above), Pallas, Juno and Vesta were discovered in the early 19th century.

For a while, they were listed as planets, but famous astronomer William Herschel, following a suggestion by Greek scholar Charles Burney Jr., coined the term ‘asteroids’, which means ‘star-like’.

Quite appropriate if you observe them through a telescope, but it completely ignores the fact that these are small rocky bodies.

Many astronomers prefer the label ‘minor planet’ or ‘small solar system body’, but the term ‘asteroid’ is still very much in use.

10

Supernova

In 1572, Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe observed a new, bright star in the constellation Cassiopeia. Just 32 years later, in 1604, Johannes Kepler saw another stella nova (Latin for ‘new star’), in Ophiuchus.

Unbeknownst to them, these were not new stars at all. Instead, what they witnessed was the death of a massive star, not its birth.

In a sense, the name couldn’t be more wrong! Incidentally, the word ‘supernova’ was only introduced in 1934, when astronomers already knew better.

For more info about these exploding stars, read our guide What is a supernova?

11

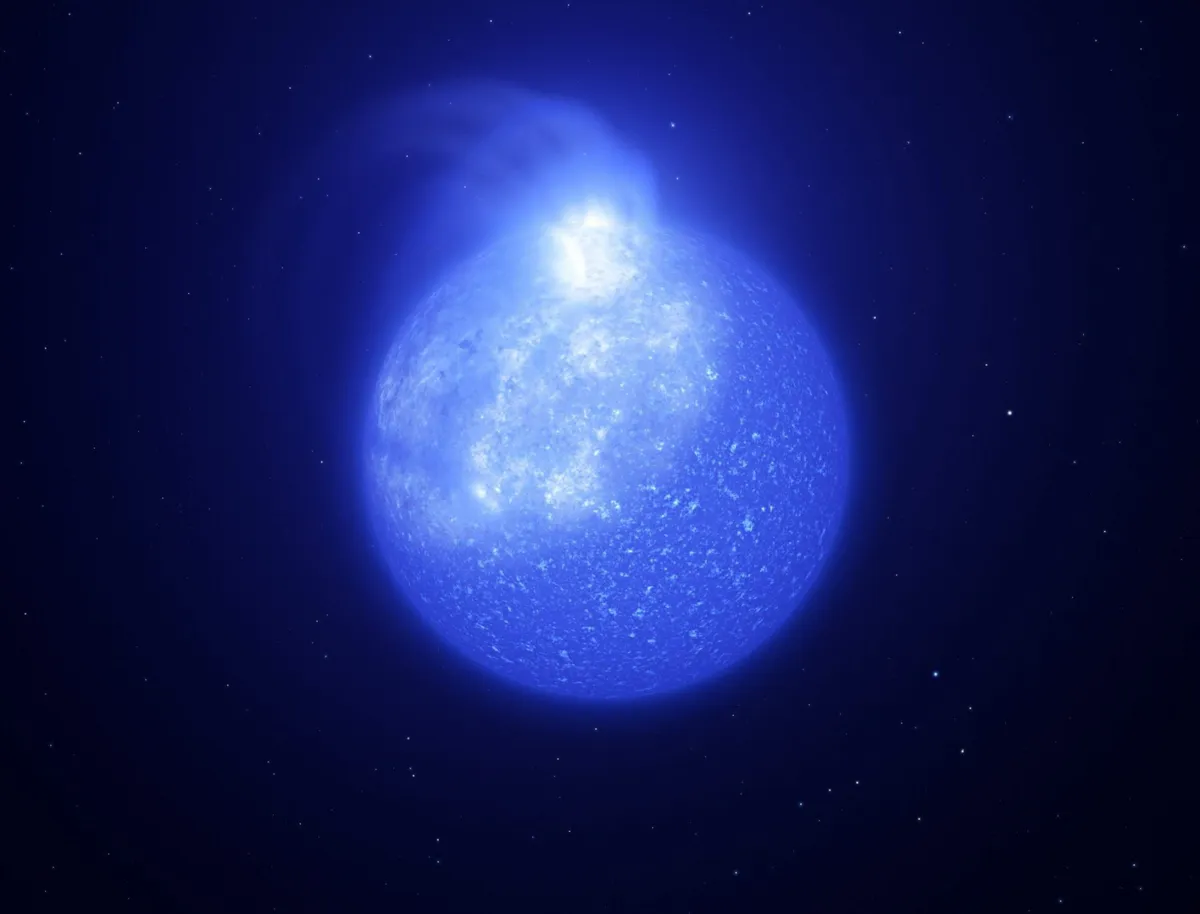

Planetary nebula

In 1790, just nine years after he discovered the planet Uranus, William Herschel was scanning the skies with his home-built telescope, and came across a small, greenish circular nebulosity in the constellation Taurus.

Before long, he had found a few others. Since they resembled the small, blue-green disk of Uranus, Herschel called these mysterious objects ‘planetary nebulae’.

Despite their suggestive name, however, planetary nebulae have nothing to do with planets. They are short-lived expanding shells of gas, expelled by ageing Sun-like stars as they turn into unstable red giants.

After the red giant contracts into a white dwarf, the gas is ionized by the energetic ultraviolet radiation of this tiny, hot star, and starts to glow in various colours, depending on the composition.

OK, so the name ‘planetary nebula’ doesn’t make sense. Or does it? Over the past decades, astronomers have come to realize that the funny, bi-symmetric shapes of some planetaries may be due to the presence of orbiting planets in the equatorial planes of the dying stars.

So there may be something to Herschel’s terminology after all. Still, an alternative name, capturing both the serene beauty of these objects and their association with stellar death, would be welcome. Any suggestions?

For more info, read our beginner's guide to nebulae.

12

Black hole

Everything that comes close falls in, so it’s a hole. It doesn’t emit any light, so it’s black. What name could be better for the most mysterious and most exciting objects in the universe?

Yet, it doesn’t fill the bill that well. First, black holes aren’t real holes of course. A better description would be a 'compactification' of spacetime.

Moreover, they’re not completely black. According to quantum theory, a black hole leaks a small amount of Hawking radiation, and its surface may even be a glowing ‘firewall’ of energetic photons.

But as long as no one really understands black holes, there’s no harm in calling them just that, don’t you agree?

For more info, read Chris Lintott's article How do black holes form?

Govert Schilling is an astronomy journalist and broadcaster, and author of Ripples in Spacetime.