You may have heard the term 'opposition' being used by astronomers before, and you may be wondering exactly what that means.

In astronomy, an opposition is the time when a planet is in the exact opposite position in the sky to the Sun.

If you look at the diagram above, where Jupiter is shown at opposition, you’ll see what’s going on. This shows the view looking down on the plane of the Solar System. Notice that only the planets further out from the Sun than Earth, known as superior planets, can achieve opposition.

On the diagram, imagine all the planets moving anti-clockwise along their orbits – the Earth moving fastest and each further planet moving more slowly as it orbits the Sun.

Read more:

- Watch our virtual planetarium

- How to find the planets in the night sky

- How to observe Jupiter and Saturn

As Earth sweeps around, it will move between the Sun and every one of the planets. It is this orbital triple line-up of the Sun, Earth and a planet that indicates the time of opposition for each planet.

This is great news if you like observing these distant worlds, because it means the planet will appear at its largest and brightest in the sky.

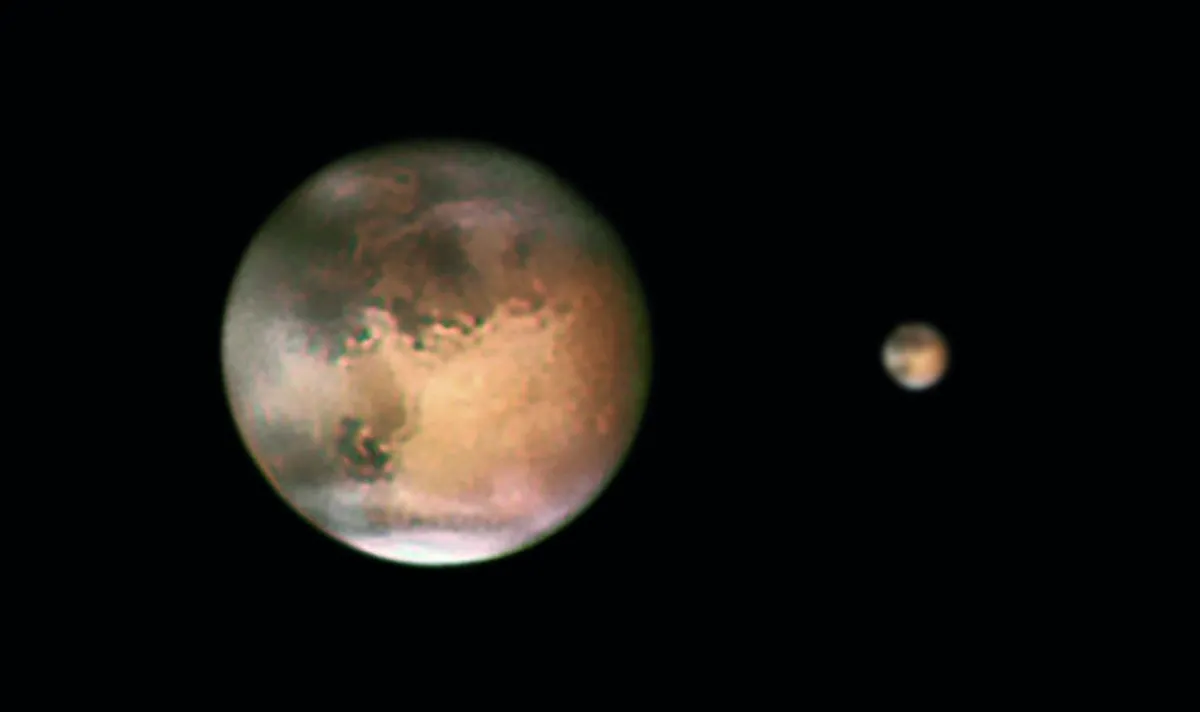

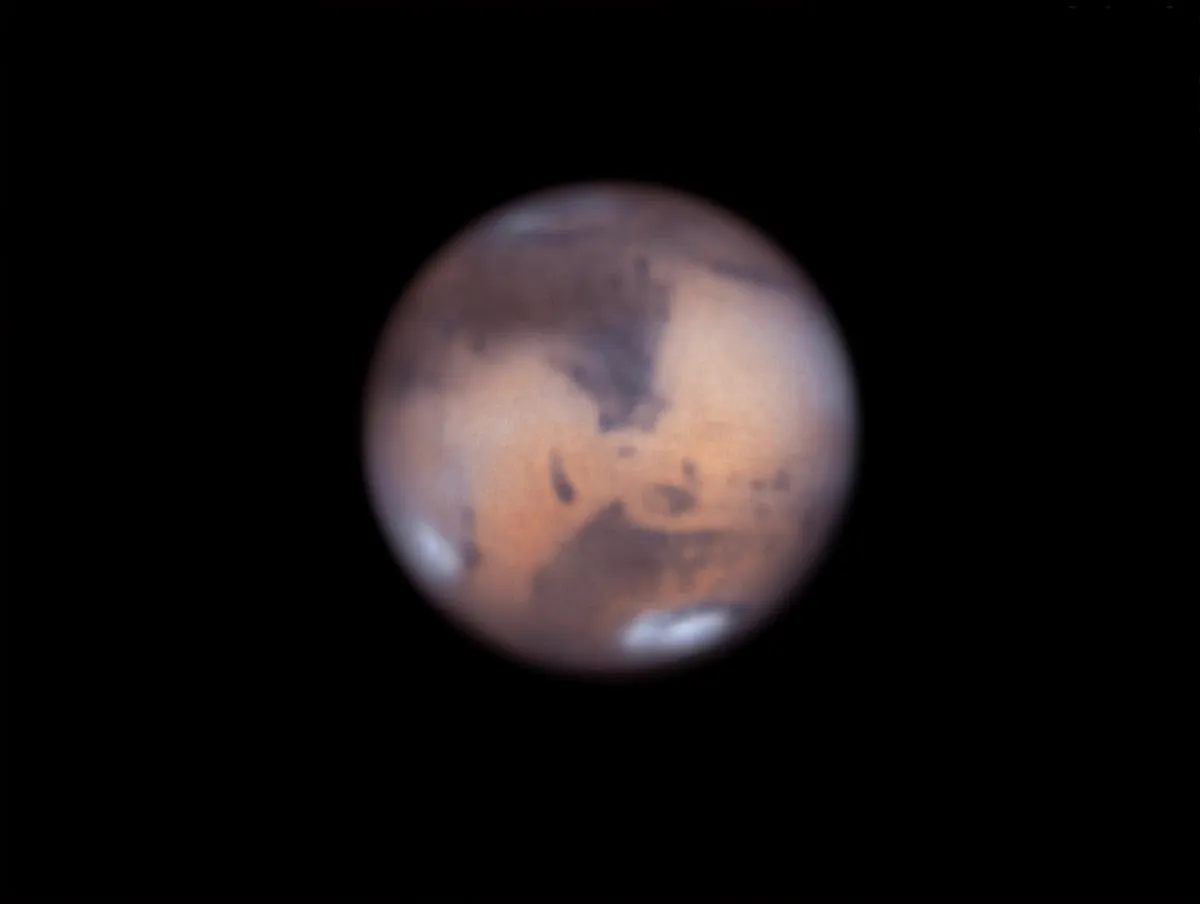

With Mars at opposition in the latter half of 2020, you can take a look at the wonderful results of this geometry, a time when any superior planet is at its closest to the Earth.

Mars at opposition

Mars is the first planet away from the Sun to us, as you can see in the diagram above, and also the one that shows the greatest change at opposition.

Most of the time, Mars is seen as a fairly small reddish disc in a telescope, but every two years and two months the planet moves into opposition.

As this event approaches, there is a dramatic increase in brightness over just a few weeks. Indeed, while sitting close to the Earth, Mars can become the second brightest planet in the sky after Venus.

In 2020, Mars will be at opposition on 13 October. Find out how to make the most of this event with our guide on how to observe Mars.

During opposition you’ll see a planet’s change in size most clearly with a telescope. With clear skies at opposition, Mars appears large in the eyepiece and you’ll be able to see incredibly fine details on the surface, as well as the larger areas such as the dark patch of Syrtis Major and the polar ice caps.

However, this sparkling ‘star’ does not last for long. As Earth’s faster orbital speed takes us away from Mars its size, and hence brightness, diminishes.

In fact, Mars has only a two-month window centred around opposition when it is best observed. This is why many keen planetary observers await such events with great anticipation.

Further out, due to the more sedate speed of the moving worlds, oppositions occur more frequently than those of Mars.

Jupiter’s slow orbit means it travels slowly across the night-time sky at a rate of about one constellation per year. The result of this is that oppositions come around every one year and one month.

You can use this time to get a closer look at the detail in the cloud belts and zones of this gaseous giant. It is also very obvious, when at its largest, that Jupiter is a squashed-looking world, its fast rotation causing the planet to take on a more oval appearance.

The fact that the outer planets are vast distances away from us means that the brightness changes also become less pronounced. Oppositions only make a few tenths of a magnitude difference to the brightness of Uranus and Neptune – the outermost planets in the Solar System.

Any planet at opposition will rise at sunset, reach its highest in the sky at midnight and set at sunrise. Therefore, you have your target as high as possible close to the darkest time of night. Everything is calling out for it to be observed.

This guide originally appeared in the April 2011 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.