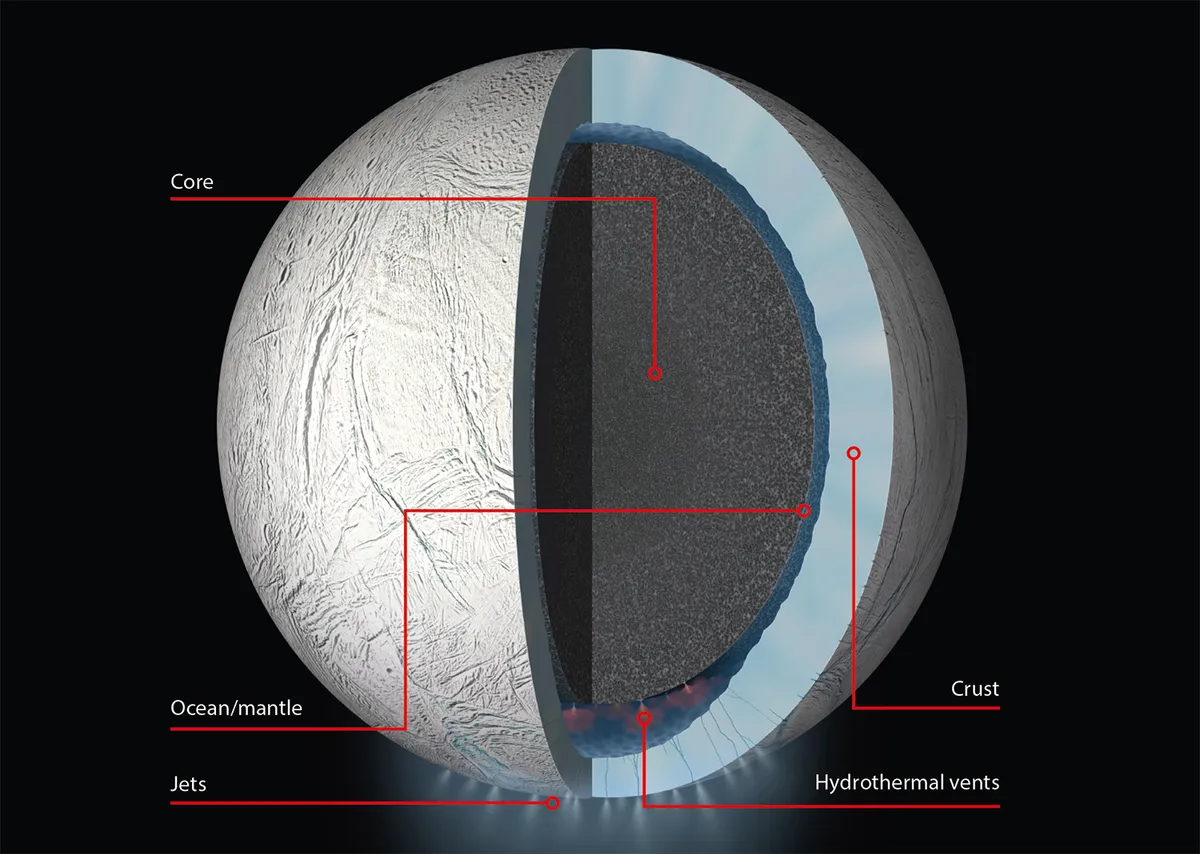

Enceladus is a medium-sized moon of Saturn made up of a crust of water-ice and an ocean of liquid water below.

The moon's ocean is similar to those on Earth and is connected directly to Enceladus’s rocky core.

More on alien life

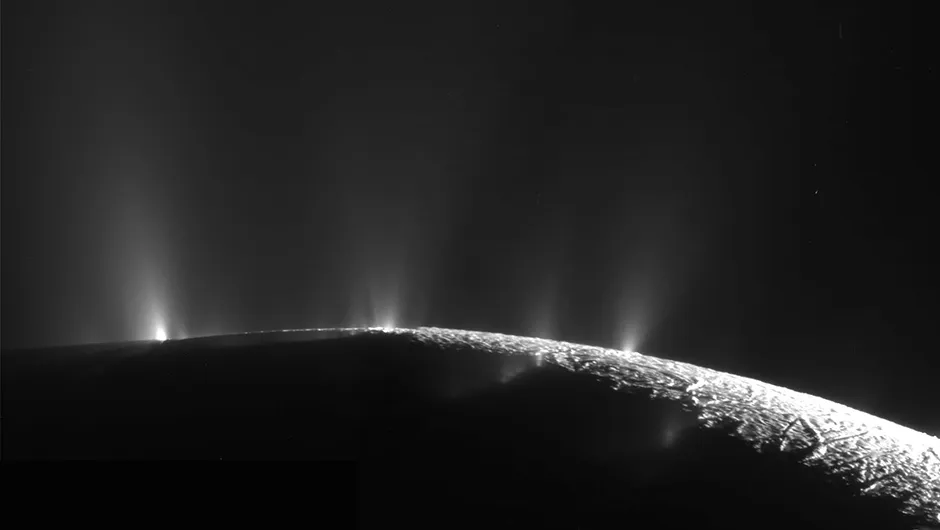

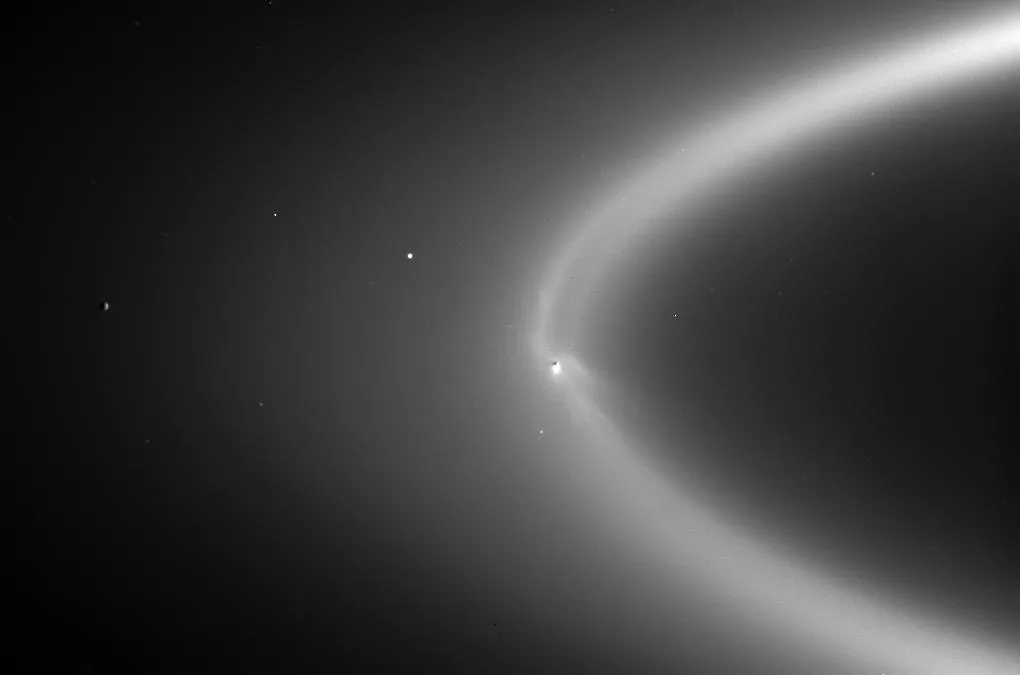

Water from Enceladus’s ocean is emitted in large jets through cracks in the icy crust near the moon’s south pole.

We know that this icy moon boasts water, heat and organics. Scientists have discovered it has complex chemistry too.

It could prove to be habitable, and is currently one of the best places in the Solar System to search for signs of life beyond Earth.

Nozair Khawaja is a planetary scientist based at Freie Universität in Berlin exploring the habitability of icy moons.

We spoke to him to find out more about this strange icy world, and why Enceladus is such a promising target in the search for life.

What causes Enceladus's jets?

The jets happen because Enceladus is orbiting a much larger body: Saturn.

Saturn’s gravitational pull causes Enceladus to stretch, compress and relax, which gives rise to an immense amount of friction.

This friction is converted into heat, which causes interactions between the water and rock and hydrothermal vents at the bottom of Enceladus’s ocean.

These vents in turn push material to the top of the ocean, where it bursts through the cracks as plumes of water vapour and ice grains.

The plumes can be enormous, reaching thousands of kilometres above the moon’s surface.

Why are scientists interested in Enceladus?

We’re searching for habitable places beyond Earth, places where there’s evidence of past life or the possibility of future life.

We think that for a place to be habitable, it should meet three ‘green lights’ – and Enceladus meets them all.

The first green light is liquid water must be present.

Secondly, an energy source is needed, which we think could be tidal heating.

Lastly, you need the right set of elements to form, support or sustain life: carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, phosphorus and maybe sulphur, as well as organic molecules.

We have detected all of these elements on Enceladus.

What did your team discover?

We found new, complex organic compounds in ice grains in Enceladus’s plumes.

To understand the significance of the discovery, we must look back at the Cassini space mission, which was in the Saturnian system from 2004 to 2017.

During its lifetime, Cassini collected measurements from lots of ice particles from Enceladus’s plumes

and from the rings of Saturn.

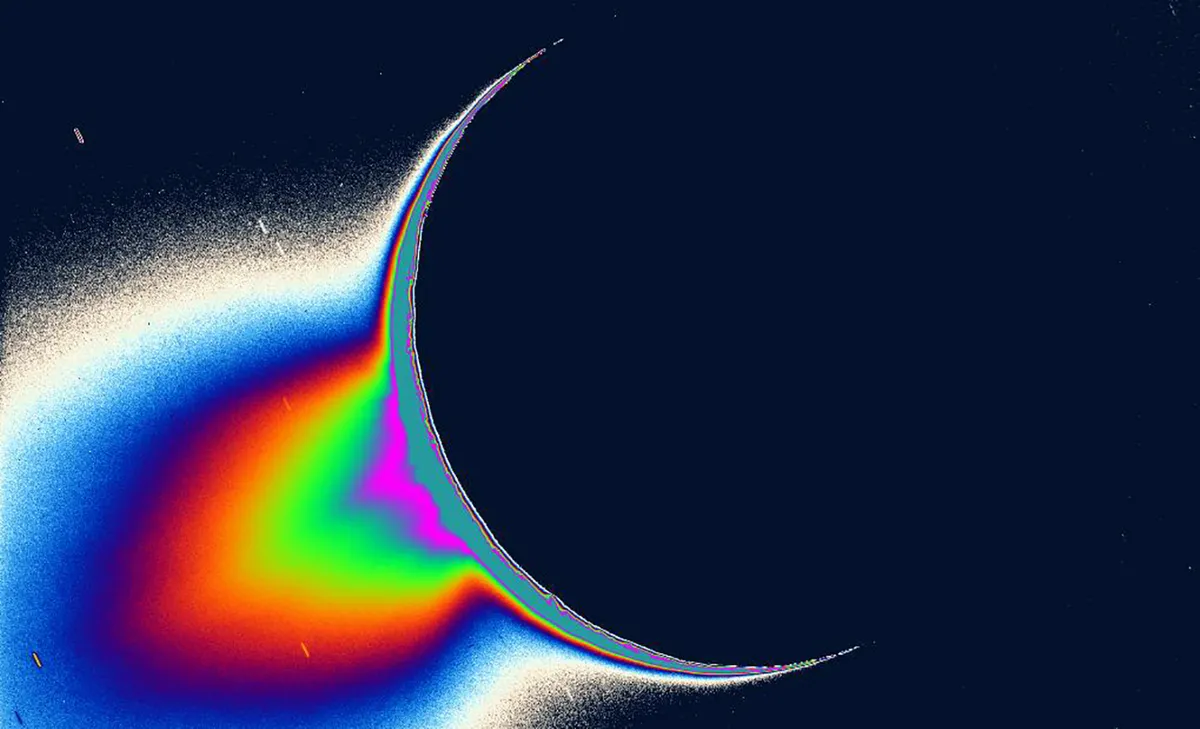

Previously, we used that data to look at older ice particles sitting in Saturn’s E ring, the second-outermost of its rings.

We knew these had been ejected from Enceladus’s subsurface oceans, but that while they sat in the E ring (for months and years), they might have been changed by the effects of radiation.

Our new research looked at ice grains collected by Cassini just minutes after they were ejected from Enceladus.

We found two interesting things: the same organic compounds in both samples, meaning that those complex compounds in the E ring had the same origin – Enceladus’s subsurface ocean; and new organic compounds that had never been seen before in ice grains ejected from Enceladus.

The bigger picture is that these organic molecules must also originate from Enceladus’s ocean and they provide a complex picture of Enceladus’s subsurface chemistry.

What does that mean for the potential for life on Enceladus?

What we can say is that all three major keystones for life exist on Enceladus, which makes it a potential candidate for a habitable environment.

I would go a step further and say that, even if we don’t discover any life there, better investigations of Enceladus will tell us something about what life might need.

For example, we will be in a better place to answer the question: if we have water, heat and organics, why isn’t there life?

What are we missing?

What’s next for your team?

We’re continuously exploring data from Cassini to understand more about Enceladus.

Enceladus is also the target for future missions; knowing what the payload of these missions should be – what instruments should be on board, what we might like to investigate – is also a target of our research.

There are also missions (NASA’s Europa Clipper and ESA’s Juice) to Jupiter’s moon Europa, another candidate for exploring habitability, currently under way.

So there’s a lot to look forward to.

This interview appeared in the December 2025 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine