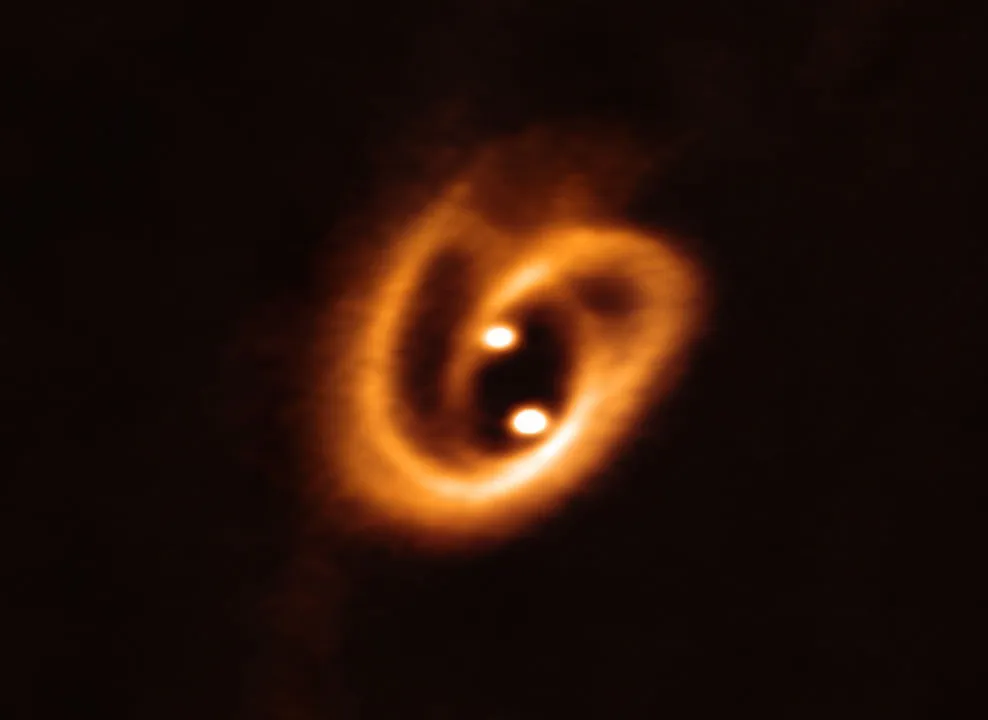

Astronomers have directly imaged a planet beyond our Solar System that's orbiting not one star, but two.

Planets orbiting distant stars are known as exoplanets, and while capturing direct images of exoplanets is extremely rare, it is something astronomers are able to achieve.

More on exoplanets

But this exoplanet image is extra special, because it shows an alien world that orbits two stars.

That means this world potentially has two sunsets and two sunrises, much like Tatooine, the fictional home of Luke Skywalker in the Star Wars franchise.

How the Tatooine world was captured

"Of the 6,000 exoplanets that we know of, only a very small fraction of them orbit binaries," says Jason Wang of Northwestern University in Illinois, USA, a senior author of the study.

"Of those, we only have a direct image of a handful of them, meaning we can have an image of the binary and the planet itself.

"Imaging both the planet and the binary is interesting because it’s the only type of planetary system where we can trace both the orbit of the binary star and the planet in the sky at the same time.

"We’re excited to keep watching it in the future as they move, so we can see how the three bodies move across the sky."

The exoplanet orbits its stars more tightly than any other directly-imaged world in a binary star system.

It's six times closer to its stars than other previously discovered exoplanets.

What makes the discovery so exciting is that it gives astronomers a glimpse into how planets form around and orbit multiple stars.

And it gives insight into how planets and stars orbit together.

A decade-long discovery

The astronomers found the exoplanet by looking back at archive data.

Wang helped commission the Gemini Planet Imager, an instrument that blocks out the bright glare of distant stars in order to detect and study planets in orbit around them.

The instrument was originally operated at the Gemini South telescope in Chile.

"We undertook this big survey, and I traveled to Chile several times," says Wang.

"I spent most of my time during my PhD just looking for planets. During the instrument’s lifetime, we observed more than 500 stars and found only one new planet.

"It would have been nice to have seen more, but it did tell us something about just how rare exoplanets are."

A decade later, Wang asked Nathalie Jones, the study’s lead author, to revisit the data.

"I didn’t think we’d find any new planets," says Wang. "But I thought we should do our due diligence and check carefully anyway."

Tracking the exoplanet

Jones, who is the CIERA Board of Visitors Graduate Fellow at Weinberg and member of Wang’s research group, analysed GPI data between 2016 and 2019.

In summer 2025, she noticed a faint object that seemed to be following the motion of a star as it moved across the sky.

"Stars don’t stand still in a galaxy, they move around," Wang says.

"We look for objects and then revisit them later to see if they have moved elsewhere. If a planet is bound to a star, then it will move with the star.

"Sometimes, when we revisit a ‘planet,’ we find it’s not moving with its star. Then, we know it was just a photobombing star passing through. If they are both moving together, then that’s a sign that it’s an orbiting planet."

"We also look at the light coming off an object," says Jones.

"We know what light from a star looks like versus what light from a planet looks like. We compared them and decided it better matched what we expect to see from a planet."

Jones verified the object was a planet that had been captured by GPI in 2016, but which had gone unnoticed.

What the planet is like

The exoplanet is six times as big as Jupiter and hotter than any planet in our Solar System.

It's 446 lightyears from Earth, which is a stone's throw in cosmic terms. It's also young, having formed just 13 million years ago.

"It’s 50 million years after dinosaurs went extinct," Wang says. "That’s relatively young in Universe speak, so it still retains some of the heat from when it formed."

The two stars orbit tightly around one another, once every 18 Earth days. But the exoplanet takes 300 years to orbit the pair.

"You have this really tight binary, where stars are dancing around each other really fast," Wang says.

"Then there is this really slow planet, orbiting around them from far away."

Next steps

The team are still trying to work out how this strange system formed, but they think the binary stars formed first, then the exoplanet formed around them.

"Exactly how it works is still uncertain," Wang says.

"Because we have only detected a few dozen planets like this, we don’t have enough data yet to put the picture together."

"I’m asking for more telescope time, so we can continue looking at this planet," Jones says.

"We want to track the planet and monitor its orbit, as well as the orbit of the binary stars, so we can learn more about the interactions between binary stars and planets."

And the team are still analysing old data to see if anything else has been missed.

"There are a couple suspicious objects," says Jones, "but what they are, exactly, remains to be seen."

Read the full paper via the Astronomy and Astrophysics journal