As NASA's Artemis programme ramps up and excitement builds around humanity's return to the Moon, could missions like this be hampering our ability to unlock the secrets of life on Earth?

That's what one science study says. The team behind the research say the exhaust methane pumped out by lunar spacecraft could contaminate the Moon.

More lunar science

These fumes could even contaminate regions of the lunar surface that hold the key to life on Earth.

And that's regardless of where the spacecraft lands and takes off from, as the damaging methane molecules could very quickly 'hop' across the Moon.

Protecting our Moon and lunar science

"We are trying to protect science and our investment in space," says Silvio Sinibaldi, planetary protection officer at the European Space Agency and senior author on the study.

He says the Moon is a natural laboratory that enables us to make vital discoveries, but somewhat ironically, the spacecraft we send to explore the Moon could "hinder scientific exploration".

The study comes as NASA prepares to send humans back to the Moon for the first time since the Apollo missions via its Artemis programme.

The US and NASA have also said they want to build a nuclear reactor on the surface of the Moon, and countries like China, India and the UK are playing an increasingly big role in lunar exploration.

But the study authors say that a knowledge and understanding of how our spacecraft could be contaminating the Moon can help build protection strategies for the lunar environment.

The secrets of life on the Moon?

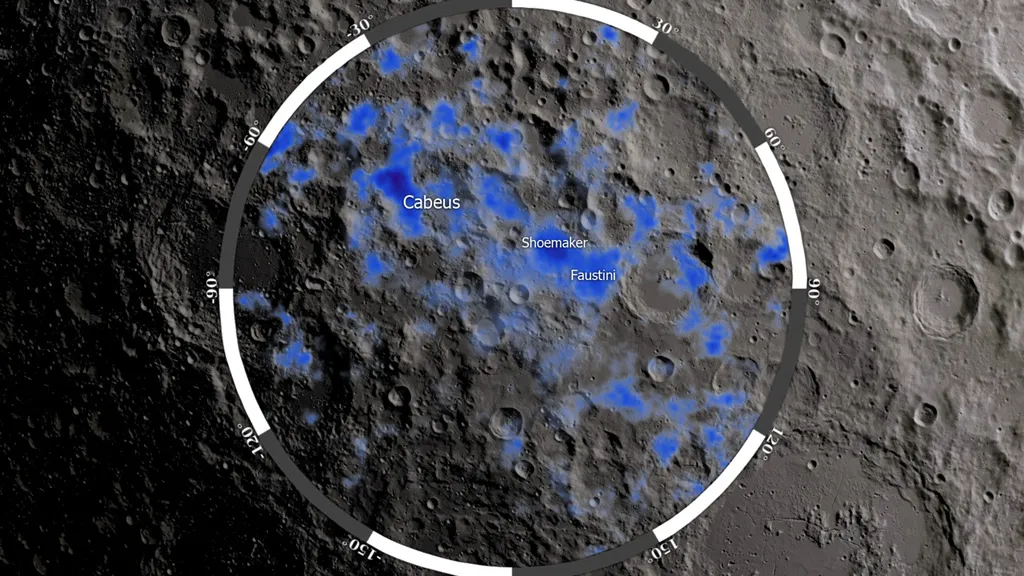

Previous observations and explorations of the Moon have confirmed the presence of water ice in craters that are permanently cloaked in shadow, where temperatures are low enough to keep water frozen solid.

It's thought this water ice could contain materials that were delivered to the Moon and Earth via comets and asteroids billions of years ago.

Could these materials contain information about how life began on Earth? Some scientists think so.

There's a possibility that the building blocks of life were delivered to Earth from elsewhere in the Solar System, by space rocks impacting on the surface of our planet.

Finding such molecules in their original form could give us the answer as to how life arose on Earth.

"We know we have organic molecules in the Solar System – in asteroids, for example," Sinibaldi says.

"But how they came to perform specific functions like they do in biological matter is a gap we need to fill."

Finding such molecules on the Moon is particularly important because Earth's ever-changing surface and plate tectonics would have likely erased any trace of the organic molecules out of which life on our planet developed.

But parts of the Moon's surface have remained pretty much unchanged for billions of years, and so could provide more pristine samples.

In permanently shadowed regions, scientists say, molecules are more likely to accumulate because cold temperatures slow their movement.

But that molecule preservation could include molecules released by spacecraft landing on and taking off from the Moon, the study authors say, potentially obscuring the evidence of materials out of which life arose.

Methane on the Moon

Study authors Sinibaldi and Francisca Paiva built a computer model to simulate how such contamination might play out.

Using the European Space Agency’s Argonaut mission – due to begin sending uncrewed landers to the Moon in the 2030s – as a case study, the computer simulations looked at how methane from spacecraft might spread across the surface of the Moon.

"We were trying to model thousands of molecules and how they move, how they collide with one another, and how they interact with the surface," says Paiva.

"It required a lot of computational power. We had to run each simulation for days or weeks."

Their model showed exhaust methane could reach the lunar North Pole in under two lunar days.

Within seven lunar days (seven months on Earth), over half the total exhaust methane had been “cold trapped” at the frigid poles.

"The timeframe was the biggest surprise,” Sinibaldi says. “In a week, you could have distribution of molecules from the South to the North Pole."

The reason is partly because the Moon has almost no atmosphere, so methane molecules can travel much more freely across the lunar surface.

"Their trajectories are basically ballistic," says Paiva. "They just hop around from one point to another."

"We showed that molecules can travel across the whole Moon. In the end, wherever you land, you will have contamination everywhere."

What can be done?

The team says colder landing sites might corral exhaust molecules better than warmer ones.

Also, the team say exhaust fumes might only settle on the surface of the ice in the permanently shadowed regions, but more analysis needs to be done to confirm if this is the case.

"I want to bring this discussion to mission teams, because, at the end of the day, it’s not theoretical — it’s a reality that we’re going to go there," says Sinibaldi.

"We will miss an opportunity if we don’t have instruments on board to validate those models."

"We have laws regulating contamination of Earth environments like Antarctica and national parks," she says.

"I think the Moon is an environment as valuable as those."

Read the full paper here