Cast your mind back to February 2025 and you'll likely remember the seven-planet parade that was visible in the evening sky.

Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune were all there for a brief moment after sunset, making for the chance to see seven planets of the Solar System in the night sky at once.

Excitement is now growing around a similar planet parade set to be visible on 28 February 2026. However, this time it's a six-planet parade because Mars is not visible this month.

Get weekly stargazing advice and Moon phases delivered to your email inbox by signing up to receive the BBC Sky at Night Magazine e-newsletter

But how visible will the planets be, and what can we really expect?

Here, we'll take a look at each of the planets in turn, revealing when they're visible and what the six-planet parade will really look like.

Firstly, though, a word on safety. Observing this planet parade will mean observing some planets low in the west just after sunset.

Make sure you do only observe these planets once the Sun is set, as looking at the Sun directly could seriously damage your eyesight.

Mercury

It feels like it's been a long time since we had good views of Mercury in the night sky.

That's because the closest planet to the Sun is an 'inferior' planet, which means it sits between Earth and the Sun, and is therefore closer to the Sun in the evening sky than the outer planets.

In February 2026, Mercury is technically an evening planet, but it sets in the west so close to sunset that it's not really visible at the start of the month.

By 19 February, Mercury reaches its furthest position from the Sun, known as 'greatest eastern elongation'.

That means that, by 28 February, Mercury is setting much longer after sunset than it did at the start of the month, but it will have dimmed considerably, making it tricky to see.

Venus

Venus, like Mercury, is also an 'inferior' planet. And like Mercury, its appearance in our evening sky will improve throughout February, setting in the west much later after sunset each night.

Venus has two advantages over Mercury in February 2026. It won't be as dim as Mercury and it will be at a higher altitude, setting later after the Sun.

That will make Venus easier to see than Mercury during the 28 February 2026 planet parade.

But by 28 February, Venus and Mercury are close together in the sky, making Venus a good jumping-off point for locating its dimmer neighbour.

Jupiter

We skip Mars and move straight to Jupiter, as the Red Planet isn't included in the February 2026 planet parade.

Although Jupiter is past its peak – which it reached in January 2026 – and is technically better viewed at the start of February, it's still the best planet to see in the night sky and the easiest to see in the planet parade.

By sunset on 28 February it's high in the eastern sky, higher than the Moon and close to bright stars Castor and Pollux in Gemini.

If you only see one planet on 28 February 2026, it's probably going to be Jupiter.

Saturn

Like Jupiter, Saturn has been quite good to observers recently, but that's changing as we approach the end of February 2026.

The best time to see the ringed planet is at the start of February, because by the end of February it's setting in the west close to sunset.

In fact, it's only just above Venus and Mercury in the evening twilight, so you'll need a relatively clear horizon to see it.

But that does mean that the western horizon will play host to a nice cluster of naked-eye planets – Saturn, Venus and Mercury – making up one half of the six-planet parade.

Uranus

An ice giant of the outer Solar System, Uranus is high in the sky in February 2026, much like Jupiter is.

Although tricky to see with the naked eye even at the best of times, it does have high altitude in its favour, making it another potentially easy member of the six-planet parade to spot.

In February 2026, Uranus is located beneath the Pleiades star cluster in Taurus.

It's best seen at the start of the month, but after Jupiter, is probably the second easiest planet to see in the sky in February 2026, even though you'll likely need binoculars or a telescope to spot it.

Neptune

The most distant planet in the Solar System has been near Saturn in the night sky for some time now, and now that Saturn and Neptune are setting close to sunset, that makes Neptune perhaps the trickiest of the six parade planets to see at the end of February 2026.

There's a nice meeting between Neptune, Saturn and the crescent Moon on 19 February.

By 28 February, Neptune will be low on the western horizon by sunset, close to Saturn. And because you'll need a telescope to see it, that means extreme caution must be taken.

Catching a glimpse of the setting Sun through an unfiltered telescope could seriously damage your eyesight, so this is something that should only be attempted by a seasoned astronomer who knows what they're doing.

The Sun will need to be fully set below the horizon before such a feat should be attempted.

The February 2026 planet parade at a glance

So what does all this mean in terms of the six-planet parade of 28 February 2026?

As we've seen, all the planets are visible from mid-February onwards, so you don't need to wait until the end of the month to try and see them in one go.

The planet parade could be visible two weeks before that date of 28 February. It's just that Venus and Mercury will be best seen towards the end of the month.

To add a bit of realism into the hype that's building around this planet parade, in reality this is not an easy alignment of planets to see.

Four of the planets set in the west just after the Sun, and one of those – Neptune – is only visible through a telescope.

There's a tendency for the hype around planet parades to suggest that six or seven planets are going to by positioned in a neat line across the sky, each one high above the horizon and visible with the naked eye.

That's never going to be the case.

But if you want to try and see the February 2026 planet parade for yourself, there are a few things you can do.

One important thing is to find a clear western horizon. Most of the planets will be clustered around the western horizon at sunset, which means you'll need all the help you can get to spot them.

You won't have much time to see Mercury and Venus before they too set below the horizon.

And, as previously mentioned, that means extreme care must be taken, so you don't accidentally catch a glimpse of the setting Sun with your naked eye or – much worse – through binoculars or a telescope.

That being said, a flat, clear western horizon could give you every chance of seeing Mercury, Venus and Saturn in the evening twilight just after sunset.

Neptune would require a telescope, and this does come with the added danger of observing the western horizon in the evening twilight.

At the same time, Uranus will be much higher in the western sky, while Jupiter will be high in the southeast, completing the six-planet parade.

Why planet parades happen

Every once and a while, planet parades and planet alignments seem to crop up, as news of multiple planets appearing in the sky, in a line at once, makes headlines.

Why do planet parades happen? They're not as unusual as you might think

When we look into the night sky and observe planets among the stars, we're really looking out across the plane of our Solar System.

After our Sun formed, the leftover star-forming ingredients like gas and dust formed a rotating disc surrounding it.

Out of this flat disc, the planets and their moons eventually formed, which is why the planets of the Solar System all essentially orbit the Sun on the same plane.

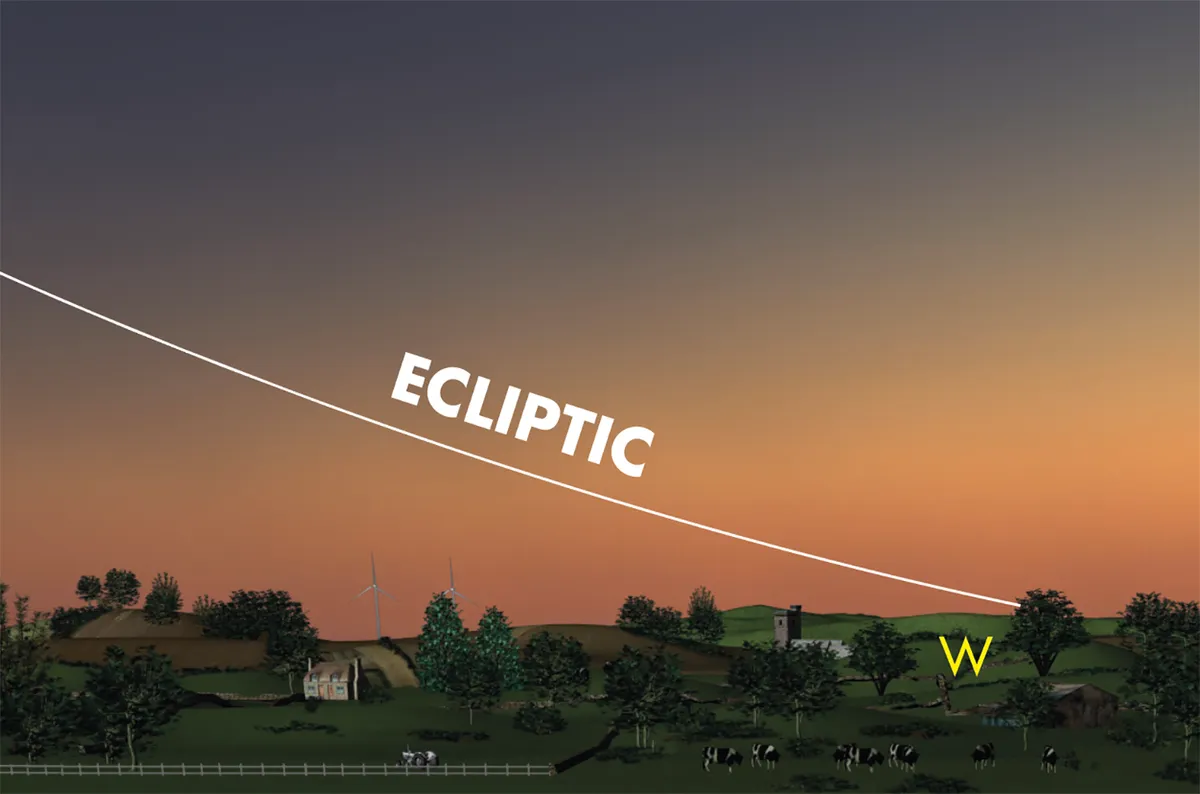

We can see this in the night sky in the shape of an imaginary line called the ecliptic, which is the path the Sun appears to travel across Earth's sky over the course of a year.

Whenever a Solar System planet is visible from Earth, it will be located near the ecliptic.

That's why, when multiple planets are visible in the sky at once, they can all be found along the same path. It's just that this path isn't straight: it's curved.

But that's also why multiple planets visible in the sky at once will all share the same patch of sky, relatively speaking, because when we look at the ecliptic in the sky, we're really looking out across the plane of the Solar System.

If you observe or photograph the planet parade, get in touch by emailing contactus@skyatnightmagazine.com