An unprecedented surge in satellite launches is threatening space-based astronomy, with a new study warning that more than 96% of images from space telescopes could be spoiled by satellites.

Published in Nature and led by NASA scientists, the study models how planned megaconstellations of low-Earth-orbit satellites will affect four telescopes: the Hubble Space Telescope and SPHEREx, plus ESA’s ARRAKIHS and China’s Xuntian, currently both still in development.

More space science

With orbiting satellites projected to reach roughly 560,000 by the late 2030s, researchers estimate that almost all images from SPHEREx, ARRAKIHS and Xuntian will be marred by streaks, light pollution or other interference.

Hubble may avoid some of the impact, thanks to its narrower field of view, but roughly 40% of its images are still at risk.

Lead author Alejandro Borlaff from NASA’s Ames Research Center warns the implications are severe.

He explains that satellites reflect sunlight, moonlight and even earthshine just enough to obliterate the faint light from distant galaxies, nebulae or exoplanets.

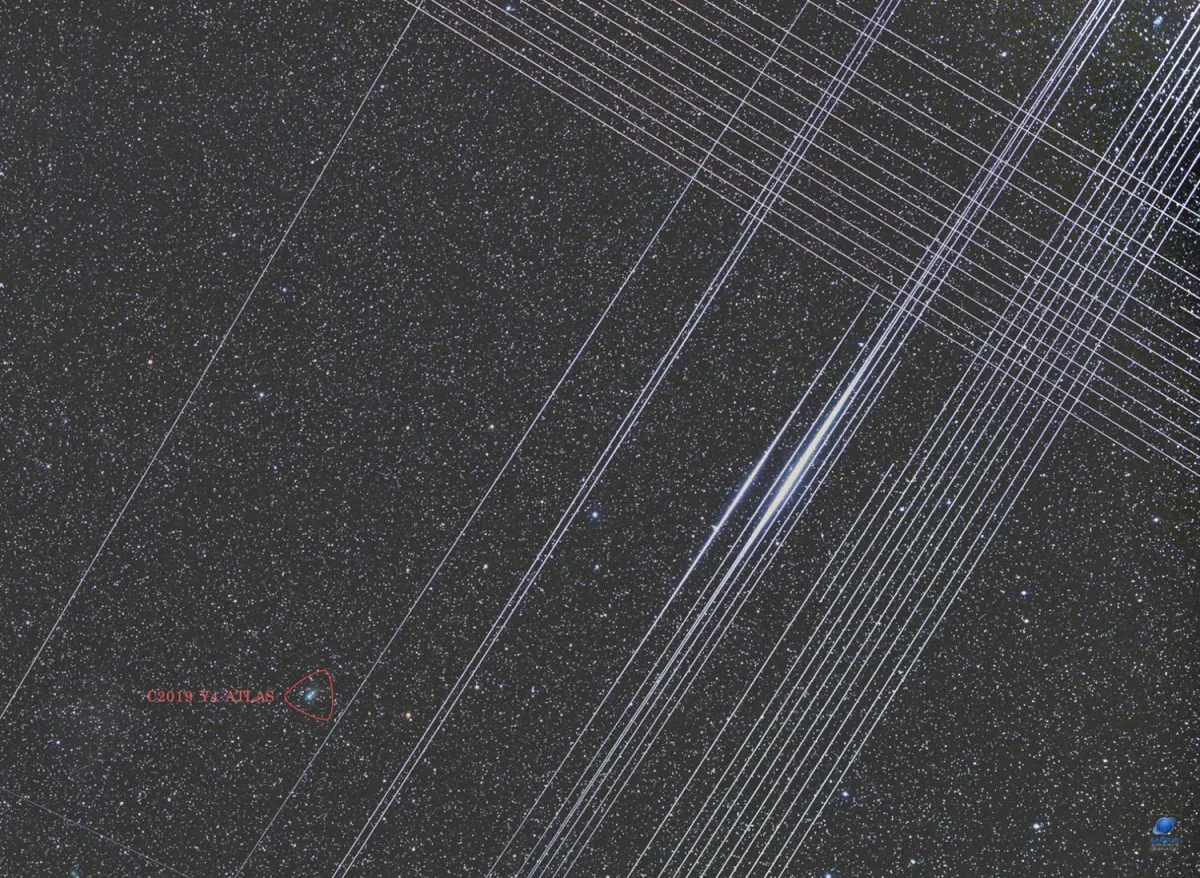

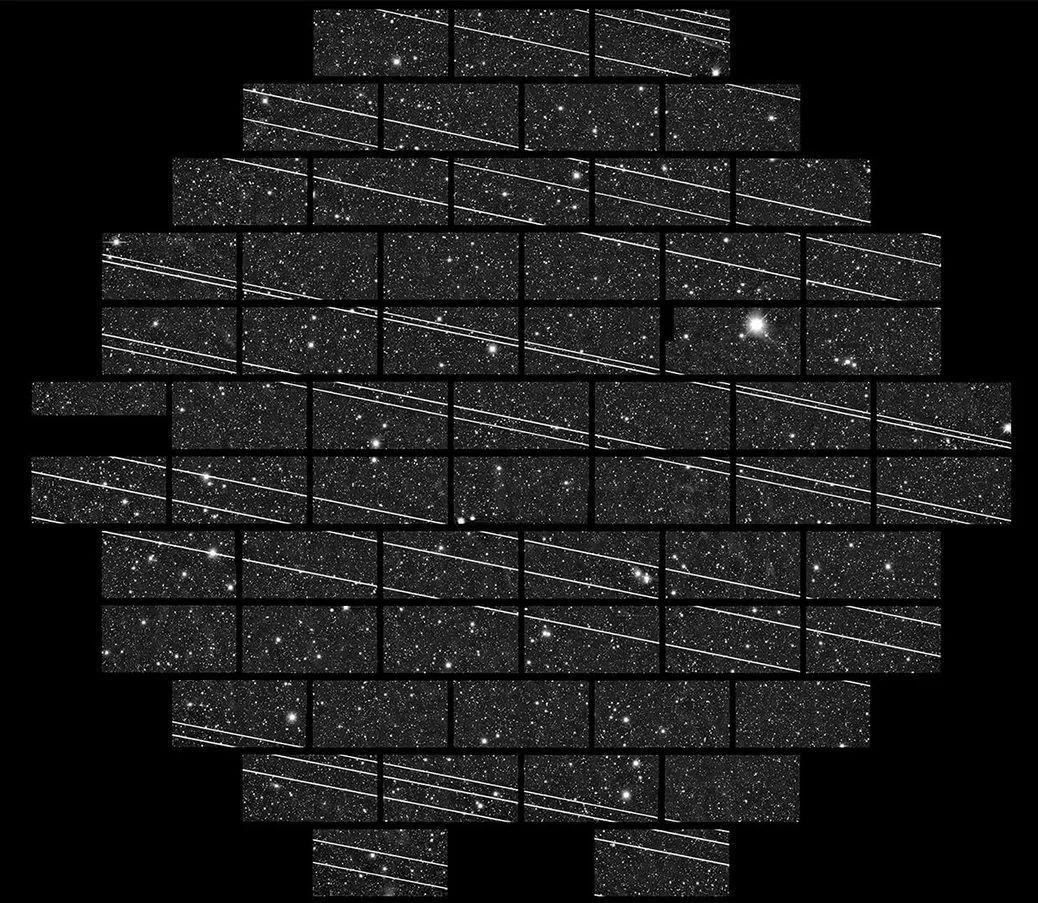

“When telescopes stare at the Universe attempting to unveil distant galaxies, planets and asteroids,” says Borlaff, “satellites sometimes cross in front of their cameras, leaving bright traces of light that erase the dim signal that we receive from the cosmos.”

The contamination isn’t just a nuisance; it jeopardises many scientific goals.

Widefield surveys, deep observations of faint objects, measurements of distant galaxies and searches for near-Earth asteroids could all be compromised. In simulations, some images contained more than 90 satellite streaks, slashing the odds of spotting faint or transient signals.

The researchers urge satellite operators, space agencies and regulators to act quickly.

Potential solutions include placing satellites in lower orbits than those in which most space telescopes operate, coordinating launch schedules or adopting ‘dark-satellite’ designs which help reduce the reflectivity of satellites.

Without such steps, the study concludes, the next two decades could mark a dark age for space-based astronomy.

However, the recommended changes would demand global coordination and strong regulatory oversight – safeguards that astronomy currently lacks.

Is it too late?

Words: Chris Lintott

As I write this, a workshop on ‘Dark and Quiet Skies for Science and Society’ by the UN’s Office of Outer Space Affairs is kicking off in Vienna – a major milestone for the hardy band of people who’ve worked for years on the science and politics of satellite interference with astronomy.

Yet I fear their efforts are not going to be enough. Unless operators are asked to justify their use of precious space in more than commercial terms, astronomy will be second in any list of priorities, behind making money.

Low Earth orbit is a shared resource that belongs to all of humanity. We need to start treating it like one, and have a say in who is using it and for what.

This article appeared in the February 2026 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.