When the OSIRIS-REx spacecraft returned its sample of asteroid Bennu to Earth, scientists around the world scrambled to get their hands on its precious cargo.

The early results justify their excitement: Bennu, which is believed to be largely unaltered since the early days of the Solar System, has surprisingly complex chemistry.

Even molecules as complex as amino acids appear to be liberally sprinkled throughout.

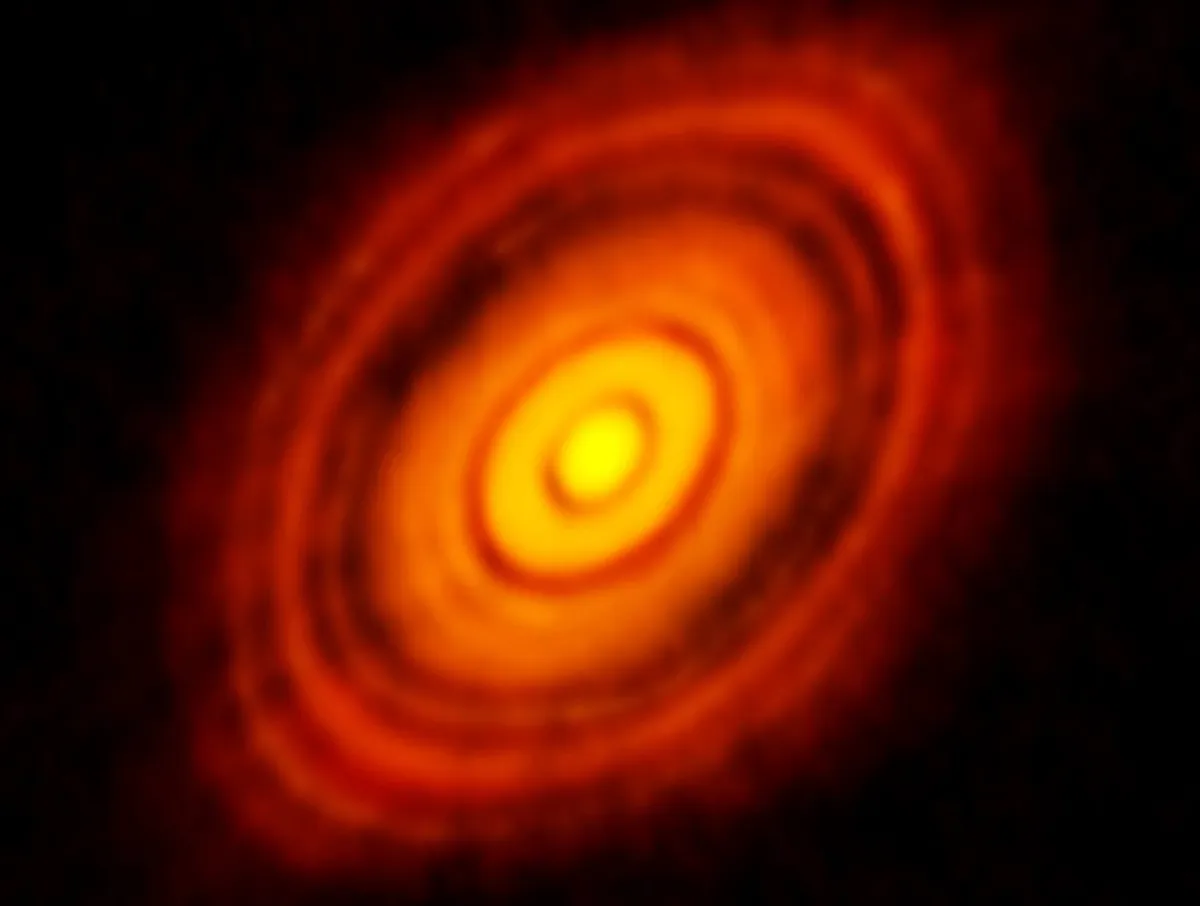

Results like these have intensified interest in the chemistry that takes place in protoplanetary discs, where objects like Bennu – and Earth – form.

More from Chris Lintott

If complex molecules form naturally in such conditions, then it’s possible that the ingredients for life could be delivered to newly formed and forming planets.

To understand the soup of chemicals we now expect in protoplanetary discs, we rely on a plucky band of laboratory chemists doing experiments here on Earth that replicate what’s happening up in space.

While they can’t reproduce the passage of millions of years, they can investigate particular processes – and that’s what Harvard astrochemistry experts have done in this one science paper.

Aromatics under fire

Their target is a class of organic molecules known as aromatics, which have structures that involve a ring of carbon atoms.

Aromatics like benzene are believed to be the building blocks from which more complex organic chemicals – like those amino acids on Bennu – can be built.

Understanding when and where they should be found, and where they might react to form other compounds, is therefore a big source of debate in astrochemical circles.

We do see these molecules in comets (in addition to asteroids like Bennu), but it’s not clear if that’s because they’ve been available for reactions from the beginning, or if they’ve reformed later on.

What we need to know is if such molecules can survive in the harsh conditions in a warming protoplanetary disc, or if the star’s radiation easily destroys them.

In the initial stages of planet formation, aromatic compounds will exist as ice, most likely mixed with simpler molecules like water and carbon monoxide.

The Harvard team created such ice within a cooled vacuum chamber, which they then irradiated with ultraviolet light.

The results show that, as ever with complex chemistry, the devil is in the details.

Whether the aromatic compounds survived their harsh treatment seemed to depend partly on how they were mixed in with the other compounds; they were more likely to survive in pure ice.

What was clear, though, was that when exposed to the kind of UV typical of a young star, aromatics rarely survived long.

On the surface of the protoplanetary disc, where there’s no hiding from the star’s light, such molecules will therefore be quickly destroyed.

In the heart of the disc, the sheer density of material will shield ice from the harsh light of the star.

And in between, there will be a region where molecules can survive, but where there is enough UV to induce chemical reactions that might be needed to process the aromatics and form more complex organics.

These relatively simple lab experiments may be pointing us to a part of the disc where all sorts of things can form and later be incorporated into newly forming planets.

Chris Lintott was reading The Survival of Aromatic Molecules in Protoplanetary Disks by Elettra L Piacentino, Aurelia Balkanski et al. Read it online at: arxiv.org/abs/2510.09797