Would you consider buying a telescope that doesn’t have an eyepiece? On the face of it, Unistellar’s eVscope eQuinox appears to challenge conventional wisdom by not including one, so we were keen to put it to the test.

When Go-To telescopes arrived 20 years ago they were hugely divisive; amateurs who had spent years learning their way around the sky felt cheated that anyone could now access the same deep-sky gems instantly.

But it’s now rare to find a telescope without Go-To capability – and the hobby has blossomed.

The Unistellar eVscope eQuinox is the latest version of the ‘smart’ digital telescope and is just as innovative.

- Buy now from Focus Camera

- Buy now from Amazon USA

Like the original eVscope from 2020, the eVscope eQuinox is a 4.5-inch, f/4 reflector that comes with a camera sensor that tracks and stacks images in real-time to produce rich-colour views of deep-sky objects.

In that respect, it’s just like the ground-based optical telescopes used by professional astronomers.

This telescope features in our list of the best telescopes for beginners and the best telescopes for astrophotography

Everything the eQuinox does is accessed through Unistellar’s app, so to view the sky with it you need a tablet or smartphone.

Up to 10 of these can be linked to the telescope via its Wi-Fi network. Your device receives the images the scope generates, which are refreshed every few seconds.

While the average 4.5-inch reflector will give you disappointing deep-sky views of galaxies, globular clusters and nebulae from urban areas, the eQuinox’s image-processing power can counter the effects of light pollution.

The Unistellar app also asks if you’re in a city, a suburb or the countryside. Armed with that knowledge, it tweaks the in-app list of recommended objects, relegating any that are likely to succumb to light pollution beyond the eQuinox’s capability.

The limit in stellar magnitude that’s visible with the eVScope is 18.0 for dark skies, but still a whopping 16.0 for urban areas.

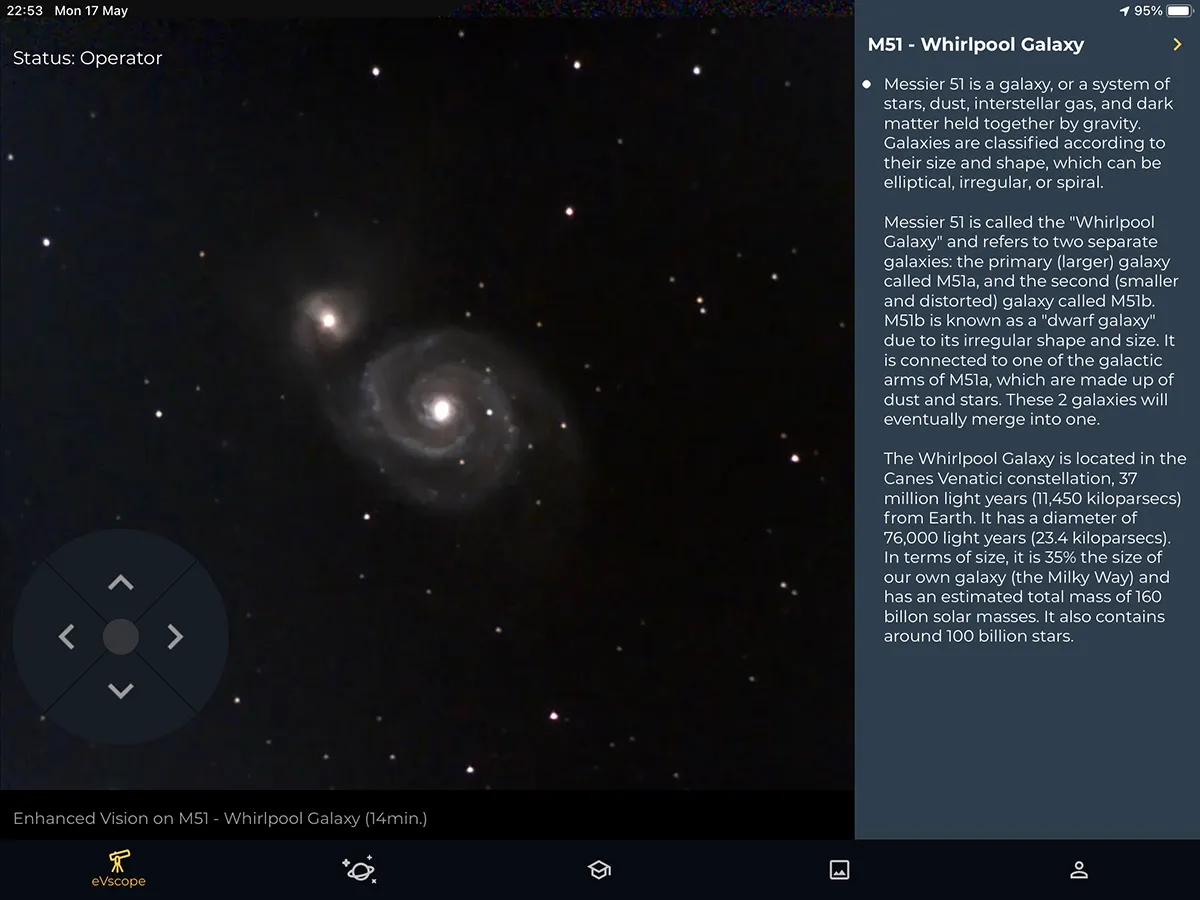

With the eQuinox trained on the Whirlpool Galaxy, M51, you can watch as lanes of stars resolve: successive images add to the detail, clarity and brightness every few seconds.

The time it takes to gather enough light to capture an object at its best depends on the object, sky transparency and light pollution.

For example, the Ring Nebula, M57, looked wonderfully bright and colourful after just 24 seconds.

M51 was similarly impactful; its galactic arms gaining colour and definition the longer the eVscope was left to track and stack.

Meanwhile, globular clusters – including M10, M13 and M71 – take only a few seconds to impress.

While the images produced by the eQuinox are ideal for viewing, sharing and learning (there are optional overlays of info), they do fall short of those that can be produced with an astrophoto-grade scope on an equatorial mount under a dark sky, over many hours.

That said, a firmware update issued during this review increased resolution from 1.2MP (1,120 x 1,120 pixels) to a much more impressive 5MP (2,240 x 2,240 pixels).

Gain, exposure time and brightness can all be tweaked and captured images are saved as PNG files to a smartphone or tablet, with only RAW data left on the telescope.

Regular uploading to Unistellar’s servers is also recommended.

The eQuinox is extremely simple to set up and although its Autonomous Field Detection software makes initial alignment easy, it’s fastest when the scope has first been manually pointed at a star-filled region of sky.

The app is user-friendly and makes it simple to select targets.

It’s also possible to manually enter coordinates of, say, a comet or a supernova that’s recently appeared, although Unistellar periodically adds such targets to the app.

It also has a citizen science dimension, asking users to observe asteroid occultations, exoplanet transits and ‘planetary defence’ tasks (potentially hazardous asteroids).

Observational data can then be uploaded for analysis by scientists at Unistellar and the SETI Institute.

The eQuinox is an easy-to-use telescope that works very well in brightly lit urban areas, with the bonus of having a scientific aspect.

It’s a new type of telescope inspired by professional, ground-based telescopes – after all, the science of astronomy is doing just fine without eyepieces.

Does the eQuinox really come with no eyepiece?

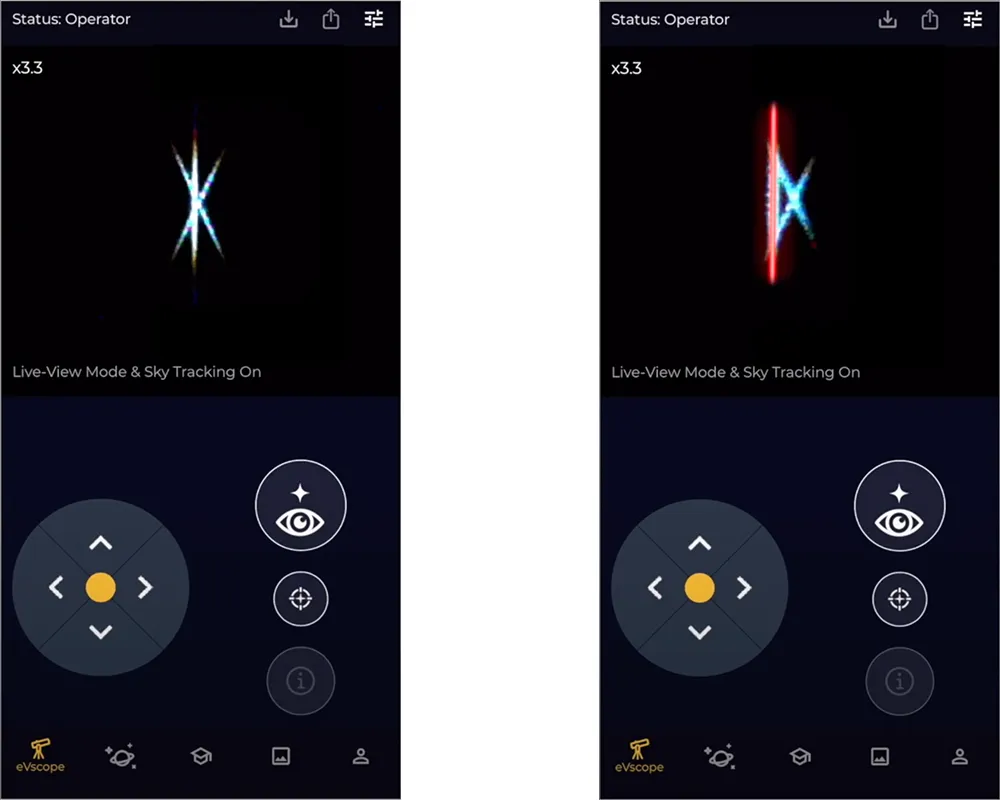

The lack of an eyepiece on the eQuinox takes a little getting used to. To focus images, instead of using an eyepiece and the focusing knob at the base of the tube as on the original eVscope, you view the image on a tablet and use the Bahtinov mask inside the dust cap.

Clicked into place across the telescope’s tube and with the eVscope pointed at a bright star, you then manually tweak the focusing knob until spikes of light streaming through the mask’s three distinctive cut-outs intersect as shown in the app view (see below).

The eQuinox can also be manually focused just as well using the Moon, but therein lies a distinct disadvantage of having no eyepiece; the eQuinox’s magnification is fixed at a field of view of 30 arcminutes.So you can never quite get the whole of the Moon in view.

But by removing the electronic eyepiece Unistellar has given this telescope two hours’ extra run-time compared to the original eVscope.

Given that some deep-sky objects, and certainly citizen-science tasks, benefit hugely from long observations, that’s a worthy improvement.

Unistellar eVscope eQuinox: best features

1

Mount

The L-shaped altaz mount contains the motor, which moves the telescope into position and then accurately tracks objects. Inside the mount are also the built-in lithium-ion battery and the on-board computer. It features 64GB storage, four times more than the original eVscope.

2

Optical tube

The mirror and sensor are inside a tube that measures 65cm long and 23cm wide. The design incorporates a 114mm (4.5-inch) diameter mirror with a focal length of 450mm (17.7 inches), which gives a focal ratio of f/4. Light is focused directly onto a Sony Exmor IMX224 sensor in a spider vane on the front end.

3

Connections

There’s an on/off switch that glows blue when switched on. The built-in battery pack is recharged via USB-C, which you can do using any portable battery. There’s also a USB-A slot on the side so you can recharge a smartphone or tablet.

4

Tripod

The tripod is designed for the eQuinox; the tube mounts on a ring at the top and is secured by two screws. The three-part legs can stretch from 59cm to heights of 133cm when fully extended. The tripod weighs 2.2kg and is very sturdy.

5

Dust cap

The dust cap that sits on the front of the telescope’s tube is there to keep it clean, but it’s got the added bonus of containing a Bahtinov mask. When clicked into place on the front of the tube, the mask can be used to focus on

a star while using the Unistellar app.

Vital stats

- Price £2,599 (plus £59 shipping)

- Optics 114mm (4.5-inch) reflector

- Focal length 450mm, f/4

- Sensor Sony Exmor IMX224

- Mount Motorised single-arm, altaz, Go-To

- Power In-built lithium-ion rechargeable (12-hour) battery

- Tripod Aluminium, adjustable height

- Ports USB-C for power, and USB-A for charging a smartphone

- App control Unistellar app for smartphones

- Weight 9kg

- Supplier Unistellar SAS

- Email contact@unistellaroptics.com

- www.unistellaroptics.com

This review originally appeared in the September 2021 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.