Science fiction is full of fantastic stories about planets entirely populated by machines, but there is actually one of those in our own cosmic backyard: Mars.

The Red Planet has had robots beeping and bleeping on it for decades – landers and rovers sent there to study its weather, analyse its rocks and send back photos of its rugged, desolate surface.

Indeed, as you read this, two hugely expensive, nuclear-powered robot scientists are trundling slowly across Mars: NASA’s Curiosity and Perseverance rovers.

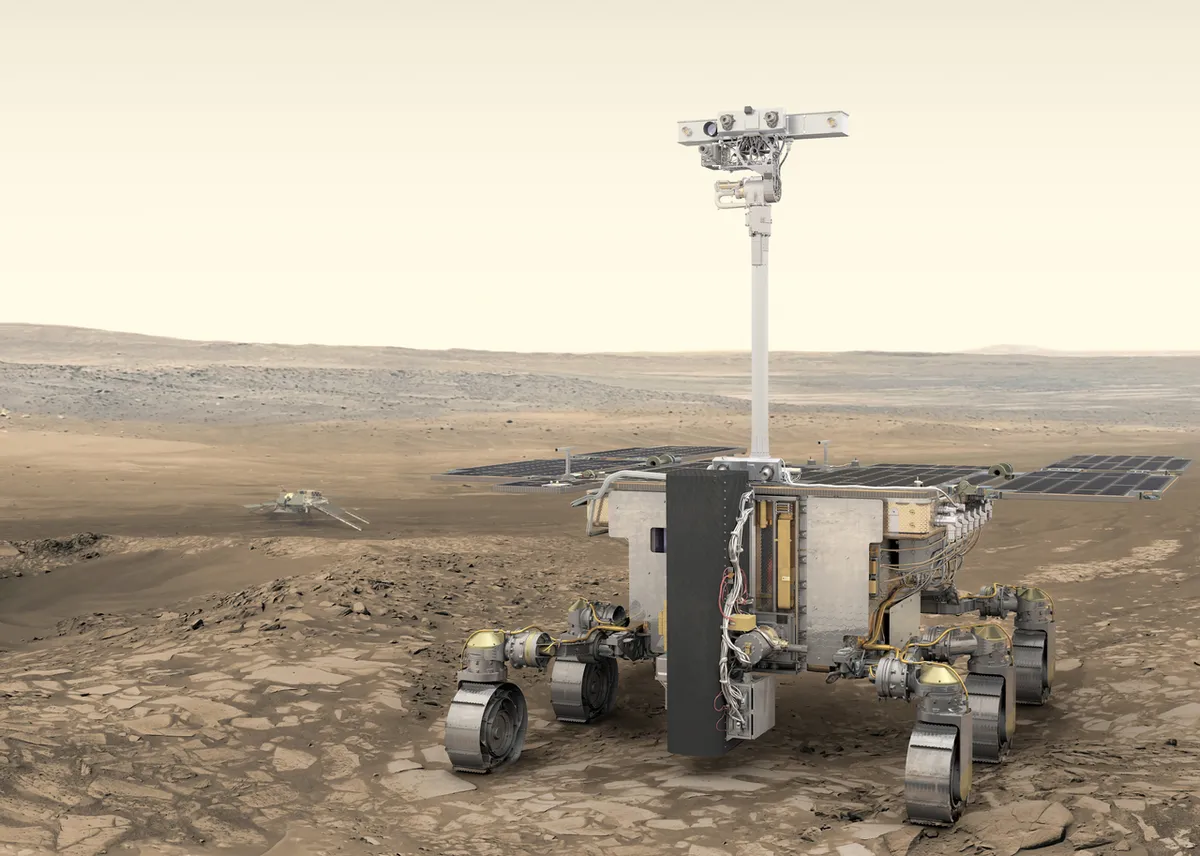

And if all goes well, there’ll be a third rover driving across the shifting cinnamon sands of Barsoom within a few years…

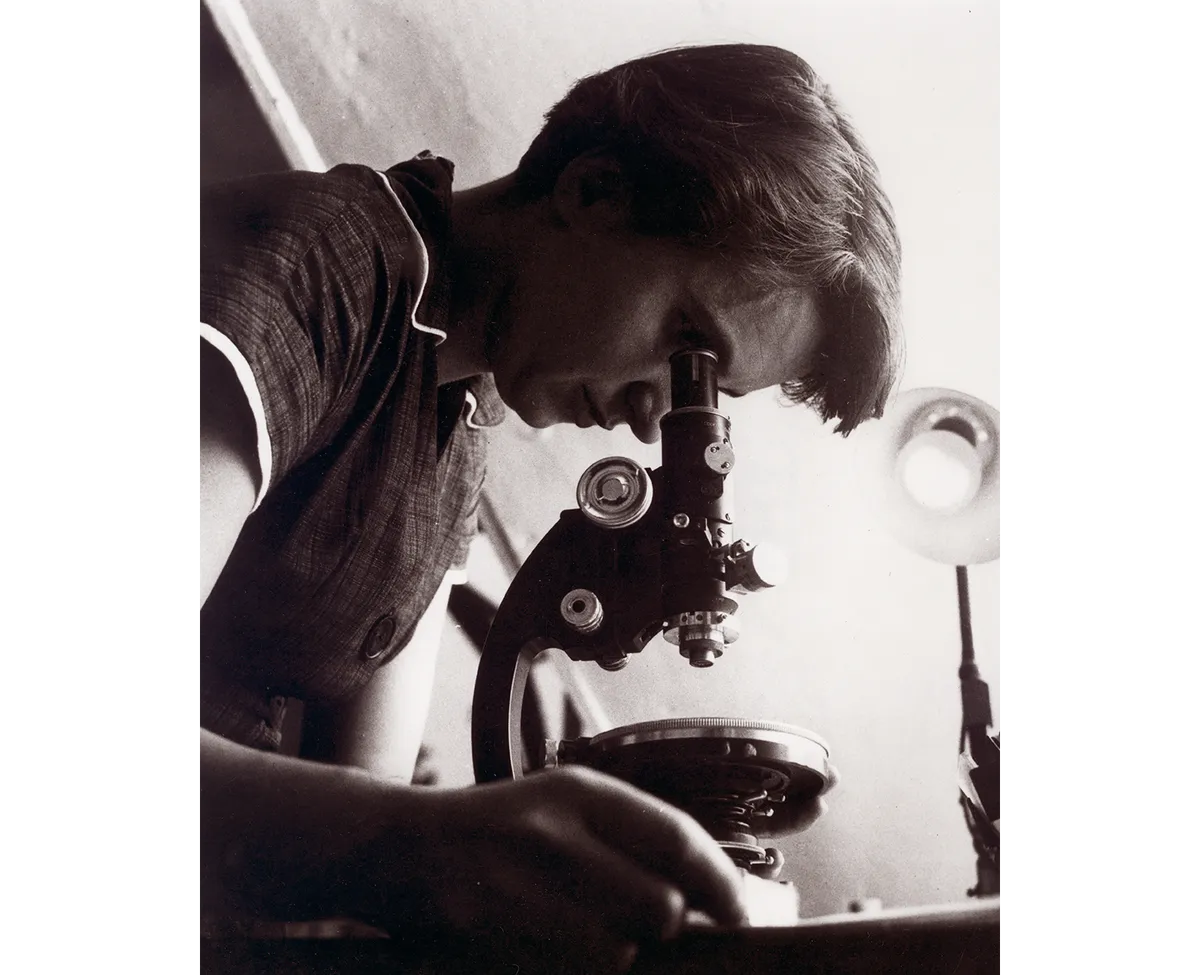

Part of the European Space Agency’s Exo-Mars programme, the Rosalind Franklin rover was named after scientist Rosalind Franklin, to honour her groundbreaking work in the field of DNA research.

An uncertain start

The rover has had a very challenging past. It was originally planned to launch in 2020, but was delayed due to technical reasons.

During that delay it went through major design changes, and was ready to launch in 2022, only to be grounded after it lost its ride to Mars on a Russian rocket in the aftermath of Putin’s invasion of Ukraine.

Its troubles are still far from over. Having missed one bus, the rover was offered an alternative ride to the Red Planet by NASA, using a commercial rocket.

But it may yet still end up forever exiled on Earth if NASA pulls its co-operation from the mission as part of its radical Trump-era budget cuts.

Credit: Airbus–M.Alexander

However, there has been encouraging news of late. The contract to build the rover’s landing platform has been awarded.

A UK aerospace company, Airbus, has been chosen to complete the touchdown system that will deliver the rover safely to Mars.

Under contract from aerospace company Thales Alenia Space (TAS), which is leading the overall ExoMars mission, Airbus teams in Stevenage, England, will design the mechanical, thermal and propulsion systems necessary for the landing platform to ensure a safe touchdown for the rover in 2030.

These systems include the landing structure, the propulsion system used to provide the final braking thrust, and the landing gear to ensure the lander is stable on touchdown.

Like the landing stages of the Mars Exploration Rovers Spirit and Opportunity, which touched down on Mars in 2004, Rosalind Franklin’s lander will feature two ramps.

These ramps will be deployed on opposite sides of the lander to enable the rover to be driven down onto the Martian surface using the safest route.

The award of this contract is a very good sign that, despite its past trials and tribulations, the ExoMars project is still very much moving forwards.

It makes it more likely the rover will actually launch in 2028, and drive away from its landing site on Mars in 2030. However, it doesn’t guarantee it.

The challenges of landing on a distant world

If it does make it off the ground, Rosalind Franklin won’t be the first European hardware to reach Mars.

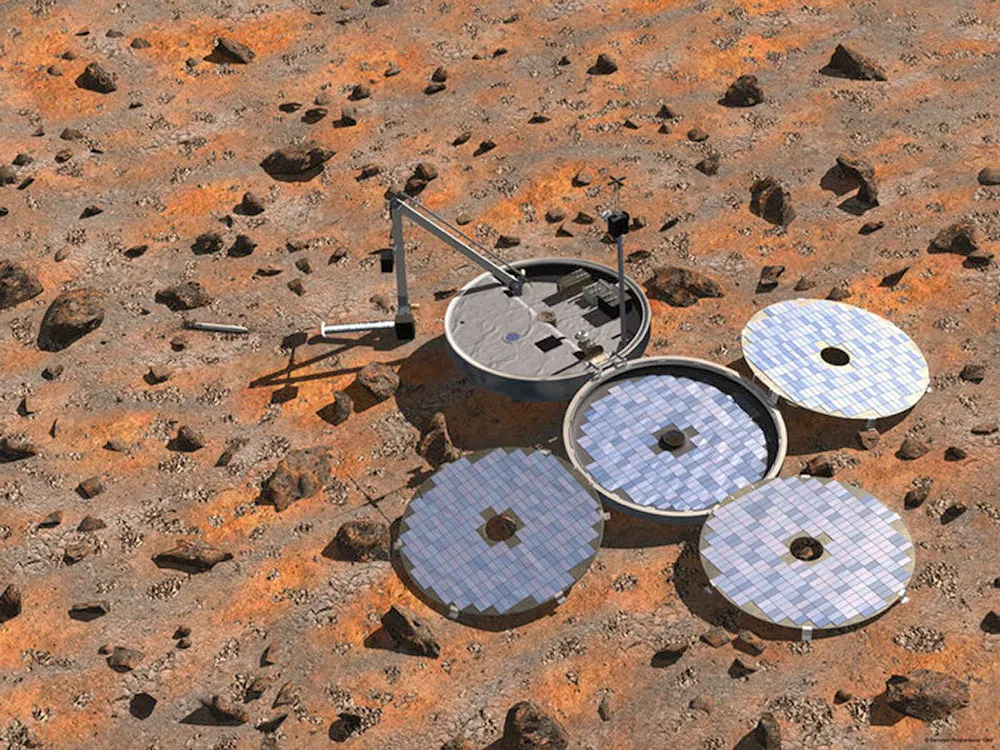

On Christmas Day in 2004, the world waited with bated breath to hear if the Beagle 2 robotic lander, taken to Mars by ESA’s Mars Express orbiter, had touched down safely.

Beagle 2 was an exquisite piece of engineering – something like a cross between a pocket watch and a Swiss Army Knife.

It was supposed to unfurl a quartet of solar panels after landing, before digging beneath the surface of Mars to look for signs of past microbial life.

Unfortunately, Beagle 2 never phoned home.

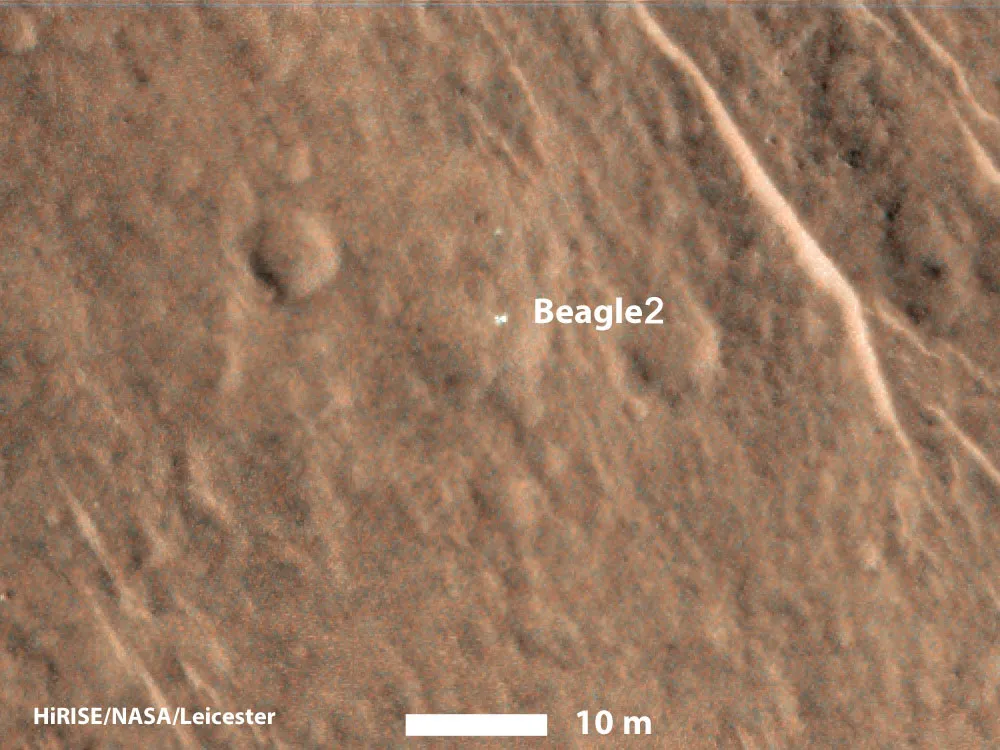

For a long time experts assumed that it had crashed, but images taken by a US orbiter 11 years later showed it had landed safely, and fully intact.

However, two of those four panels had failed to fully open, blocking its communications antenna and leaving it unable to carry out its mission.

In March 2016, the ESA sent Schiaparelli to Mars.

This wasn’t a probe with cameras and instruments designed to study Mars itself, but an ‘entry, descent and landing demonstrator module’ designed to test landing technologies for future Mars missions.

On 19th October, Schiaparelli reached Mars and its parachute opened correctly.

Unfortunately, its onboard computer miscalculated its altitude and, thinking it was closer to the ground than it actually was, released its parachutes too early.

Its braking thrusters fired, but not for long enough to slow it down for a safe landing. It smashed into the surface at high speed.

Rosalind Franklin rover's science goals

If Rosalind Franklin succeeds where Beagle 2 and Schiaparelli failed, it will send back beautiful wide-field and close-up colour images of Mars.

This is what every other rover sent to Mars has done, but the Rosalind Franklin rover isn’t merely a European copycat version of NASA’s Curiosity or Perseverance.

It’s a very sophisticated machine that will be capable of undertaking unique and potentially history-making research on Mars: neither of those US rovers can do that.

The rover might share Perseverance’s goal – to investigate whether Mars once harboured life by analysing subsurface samples, which are better protected from radiation – but it will dig deeper into those secrets, literally.

The European rover will carry a revolutionary drill to collect samples of rock and material from 2 metres below the surface, much deeper than Perseverance can drill.

It will then analyse the samples in its onboard astrobiology laboratory – the Mars Organic Molecule Analyzer (MOMA) – looking for traces of organic compounds.

Rosalind Franklin also carries several spectrometers to study the composition of the Martian rocks and minerals.

With all these instruments working together, when the Rosalind Franklin rover finally lands in Oxia Planum, a region chosen because observations and studies conducted from orbit have shown it to be rich in clay minerals that may preserve ancient organic material.

If there was once life on Mars, there’s a good chance that Rosalind Franklin will find it.