When it comes to blockbuster musical depictions of outer space, Gustav Holst’s The Planets is where it all began. The bespectacled, unassuming British composer smashed it: seven planets captivatingly imagined in sound.

This undisputed masterpiece was first heard at London’s Queen’s Hall on 29 September 1918, and it still entrances audiences around the world today.

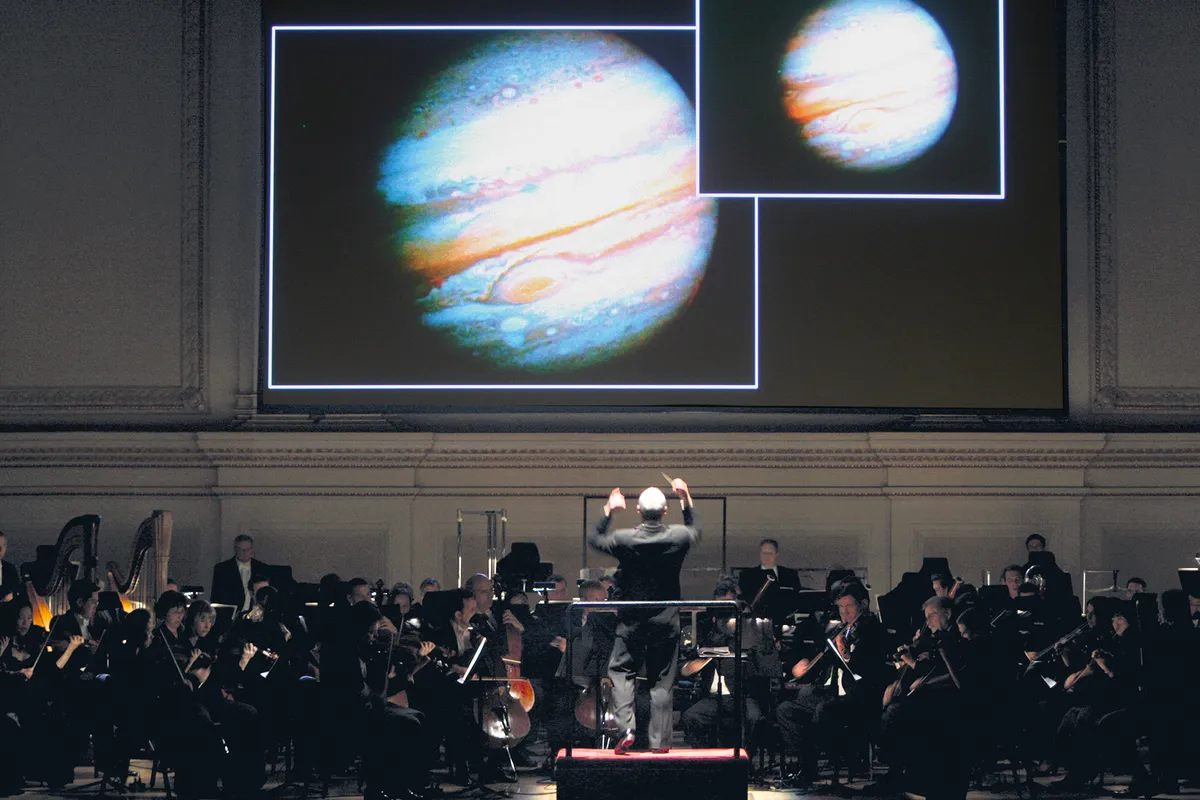

Listen to the music while contemplating planetary images in a darkened room and it’s impossible not to be moved.

The Planets was largely composed during the Great War, although ‘Mars: the Bringer of War’ (which Holst wanted to sound ‘terrifying’) in fact predates the conflict.

Read more about the history of astronomy:

- How The Sky at Night was born

- The history of the Royal Astronomical Society

- Music of the spheres: a journey of orchestral astronomy

Holst wasn’t medically fit to fight in the war, but in late summer 1918 the YMCA invited him to organise musical activities for troops stationed in Salonica (modern-day Thessaloniki, Greece).

The finishing touches to The Planets were inscribed at the YMCA’s London HQ, while Holst sat waiting for his papers.

That first performance was given thanks to financial support from a benefactor – Holst’s friend and fellow composer Henry Balfour Gardiner – and rushed through before Holst departed; the orchestra was only able to rehearse for a couple of hours before that historic first performance took place.

The Musical Times declared The Planets “one of the most ambitious achievements in modern British music,” although some critics were nonplussed.

Too modern for them. “Noisy and pretentious”, said one. Very soon, though, it was recognised for what it is: a musical phenomenon like no other.

Space, the vinyl frontier

As early as 1921 The Planets was available in a complete recording, Holst himself conducting the London Symphony Orchestra.

This Columbia New Process Records release (‘The Only Records Without Scratch!’) cost a stiff (but not astronomical) 52s 6d. That’s a bit over £2 – more than a hundred quid now.

Debate continues over Holst’s motivation for writing the music. Yes, his new-found curiosity for astrology had something to do with it (reflected in the subtitles given to the music for each planet), but Holst detested being asked what the work ‘meant’.

Besides, any debate is meaningless to the millions of Planets admirers who’ve known instinctively that this stunning music evokes the wonder and mystery of outer space.

To understand the immediate impact of The Planets it’s surely relevant that it was written during the first great era of popular astronomy.

Ever more sophisticated photographic wizardry enabled the capture of jaw-dropping images from around the cosmos.

These found their way into books, newspapers and journals (such as The Observatory, which is still going strong).

Magic lantern slides of celestial objects were a staple at public lectures across the country.

Speakers could record their discourses on heavenly bodies using the newly invented spectroscope.

In the same month The Planets made its debut, the Leicester Literary and Philosophical Society was advertising its forthcoming lecture ‘Astronomy in Daily Use’ by Arthur Hinks, Gresham Professor of Astronomy.

Early in 1918, a Miss Iris Yeoman had given a course of lectures on astronomy in Bath, “Specially Suited for Children”.

Astronomy for the masses

The steady trickle of books on astronomy in the 19th century had become a flood by the second decade of the 20th.

One go-to reference volume in 1918 would have been Sir Frank Dyson’s recent Astronomy: a Handy Manual for Students and Others.

A Scottish newspaper, the Kirkintilloch Herald, listed Practical Astronomy by H Macpherson FRAS as one of its ‘People’s Books’ in 1918.

And if ‘practical astronomy’ was indeed your goal, then RAE Opticians in Glasgow was ready to mail you a telescope.

Prices ranged from 30/- to 105/- (£1.50 to £5.25 which equates to around £80 to £250 in today’s money).

In an age before TV, radio and all things online, people got out more. Remember?

And meetings of local astronomical associations were increasingly popular destinations.

The umbrella organisation here was the British Astronomical Society, formed in 1890 specifically to support amateur astronomers.

Its initial 48-member council included four women, including Elizabeth Brown (head of the BAS’s Solar Section) and the legendary Agnes Mary Clerke, author of the best-selling (and still highly readable) A Popular History of Astronomy in the 19th Century.

Planetary influence

Amateur astronomers in wartime must have found plenty to distract them up above, then. And there was more. Much more.

Remarkably, one of the 20th century’s landmark celestial events happened to be observable that very summer The Planets premiered.

Namely, the brightest nova recorded in the era of the telescope: V603 Aquilae (aka, Nova Aquilae 1918) in the constellation Aquila.

This reached a peak magnitude of −0.5. The sighting was big news, even making an impression on the man in the street.

So audiences for the first performances of The Planets are very likely to have included those who pondered the marvels of the Universe.

By the mid-1920s it had been performed on multiple occasions in the UK and other English-speaking countries, including the US.

It also triumphed in cities not renowned (even now) for taking much interest in British music: Vienna, Berlin, Paris, Rome.

The Planets gave Gustav Holst a public profile no other work of his achieved.

It was a matter of deep civic pride in his home town of Cheltenham, which in 1927 presented Holst with a celebratory painting by local artist Harold Cox.

This featured a Cotswold night sky showing the planets that had been visible when the famous work was first performed.

The Planets’ influence on music since? Hard to pin down, but any composer writing ‘space music’ now must be aware of this intimidating predecessor.

Royal Philharmonic Orchestra managing director James Williams suggested on the radio earlier this year that it’s difficult to imagine that John Williams’s music for Star Wars wasn’t inspired by Holst to some degree.

Strong in the Force, The Planets is.

Playing the planets

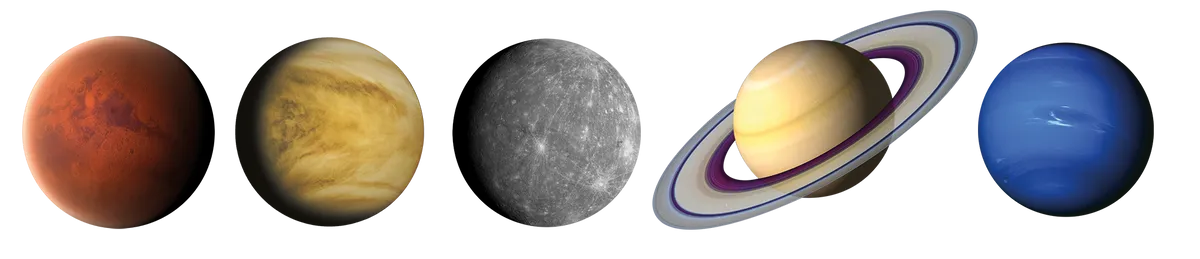

The Planets, in performance order, comprises: Mars, Venus, Mercury, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune.There’s no need to argue about Pluto’s planetary status; it simply hadn’t been sighted by 1918.

Musical considerations meant Holst didn’t order his Planets according to their distance from the Sun.The music for five of Holst’s Planets in particular suggest images with which the astronomer can identify.

Mars

Mars is frighteningly depicted as ‘The Bringer of War’, which references the fiery appearance of ‘The Red Planet’.

Venus

This movement, subtitled ‘The Bringer of Peace’, reflects the beacon that is the brightest in appearance of all our Sun’s planets.

Mercury

‘The Winged Messenger’ is a skittish, helter-skelter depiction of a planet that races round the Sun on the most rapid orbit of all – just 88 Earth days.

Saturn

‘The Bringer of Old Age’ is a wonderful contrast to Mercury, reflecting the ponderously moving planet, with a lethargic orbit of 29 Earth years.

Neptune

‘The Mystic’ rounds off Holst’s masterpiece in ethereal fashion, taking its cue from the far-distant planet’s mysterious blue hue.

Andrew Green is an oral history research fellow at the University of Hertfordshire, and the proud owner of two telescopes. This article originally appeared in the September 2018 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.