Contrary to what Pink Floyd say, there is no dark side of the Moon. The Moon rotates on its axis once every orbit around Earth, and so, like us, experiences day and night periods (albeit very protracted).

But this tidal locking does mean that one side of the Moon always faces our planet – and there’s a curious difference between the lunar near and far sides.

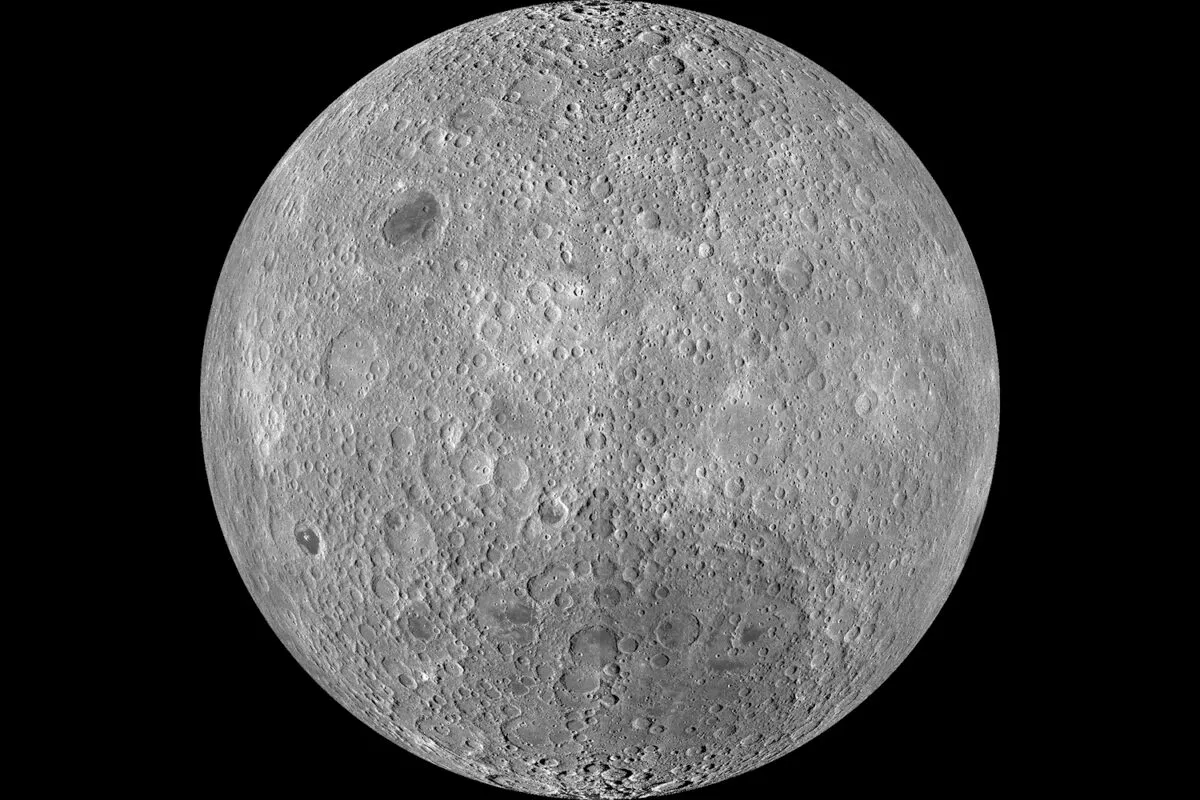

The near side is dominated by vast, dark plains of solidified lava – the maria or ‘seas’ – whereas the far side is more heavily cratered, with mountainous highlands.

In fact, the almost complete lack of dark maria means the far side is actually brighter than the side facing us.

The Moon has a fundamental asymmetry in its surface structure: the crust is much thicker on the far side than on the near side.

How our Moon formed

Scientists think they’ve got a pretty good handle on how the Moon formed. Very early in the Solar System’s history, a Mars-sized object – known as Theia – slammed into the proto-Earth.

The massive amounts of material thrown into orbit coalesced into the Moon, with both planet and its new satellite remaining molten for a significant period afterwards.

Minerals crystallised as the Moon’s global magma ocean cooled, with the lightest of these, such as plagioclase, floating to the top to form the grey-coloured crust.

But it’s still something of a mystery as to why the Moon formed with such a stark contrast between the far-side and near-side crust, a conundrum that’s known as the ‘lunar far-side highlands problem’.

Solving the Moon mystery

Various theories have been proposed over the decades to explain this difference between the Moon’s two sides.

Perhaps there was a difference in the number of impacts striking the near side and far side? Or maybe more minerals condensed on the far side from a searing, rocky atmosphere?

But many of these competing explanations fail to account for all the observed features of the Moon.

For example, in 2011, Martin Jutzi and Erik Asphaug argued that maybe a second, smaller satellite also formed after the giant impact, and later splatted itself across one side of the Moon.

However, this doesn’t fit with the smooth variation in elemental abundances around the lunar surface.

Now, Wenshuai Liu in Henan Normal University’s school of physics, China, has come up with a new hypothesis.

He argues that after the Moon became tidally locked, the two sides experienced different levels of heating.

The far side, warmed only by sunlight would have cooled to a temperature of around –20°C.

But the near side would have been kept at nearly 1,000°C by the heat radiating from the still-molten surface of Earth.

Liu compares the situation to lava exoplanets orbiting so close to their host star that the near side is hot enough to melt rock.

This lunar temperature gradient set up a global circulation in the magma (like water convecting in a saucepan), with cooler, denser material downwelling on the far side and a surface current flowing from near to far.

Floating plagioclase crystals were transported to pile up into a much thicker crust on the far side; as the far side was cooler, crystallisation here would also be more efficient.

It’s a neat explanation for the lunar far-side highlands problem.

But at the moment, Liu’s hypothesis is just that – a supposition, one that he plans to test very soon with simulations of the proposed process.

Lewis Dartnell was reading Origin of the Lunar Farside Highlands from Earthshine-induced Global Circulation in Lunar Magma Ocean by Wenshuai Liu Read it online at: arxiv.org/abs/2509.11199