How many planets are there in the Solar System?

It sounds like an easy question, but it’s more complex than you might think – and actually it’s one we still can’t answer.

With scientists finding evidence that there’s another one, or even two, just waiting to be discovered beyond Neptune, let’s take an in-depth look at the century-old search for the elusive ‘Planet 9’.

Finding Pluto

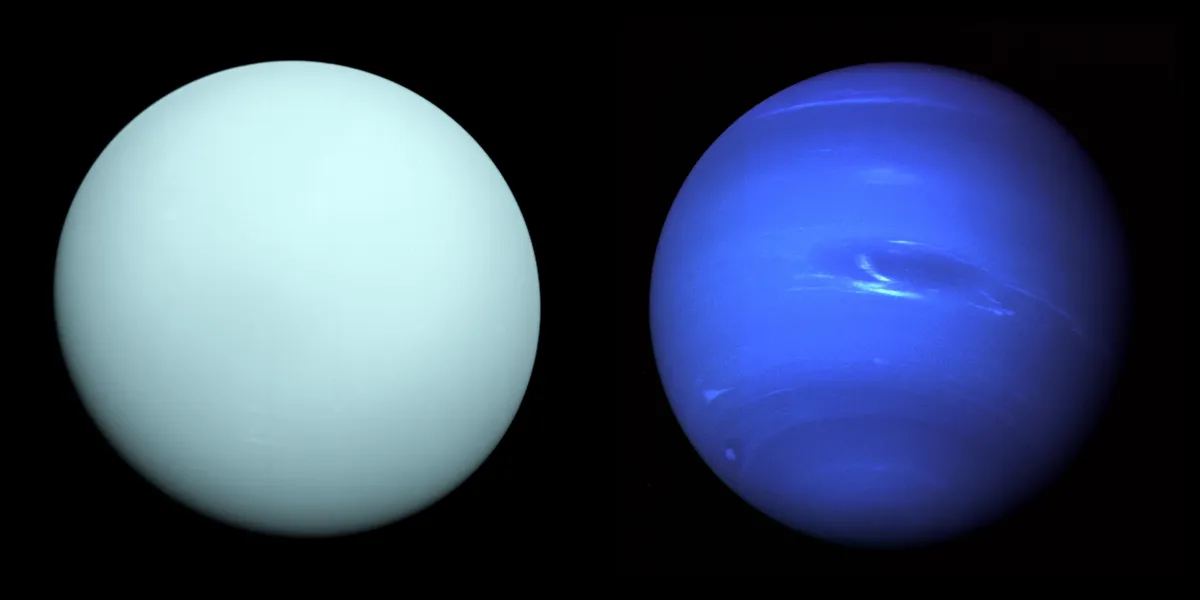

It all started back in the early 1900s, when astronomer Percival Lowell was hunting for a hypothetical ninth planet – Planet X – outside the orbits of Uranus and Neptune.

Uranus’s orbit was odd – it didn’t seem to match our predictions – but if there was a large and distant planet out there disturbing it, it could all make sense.

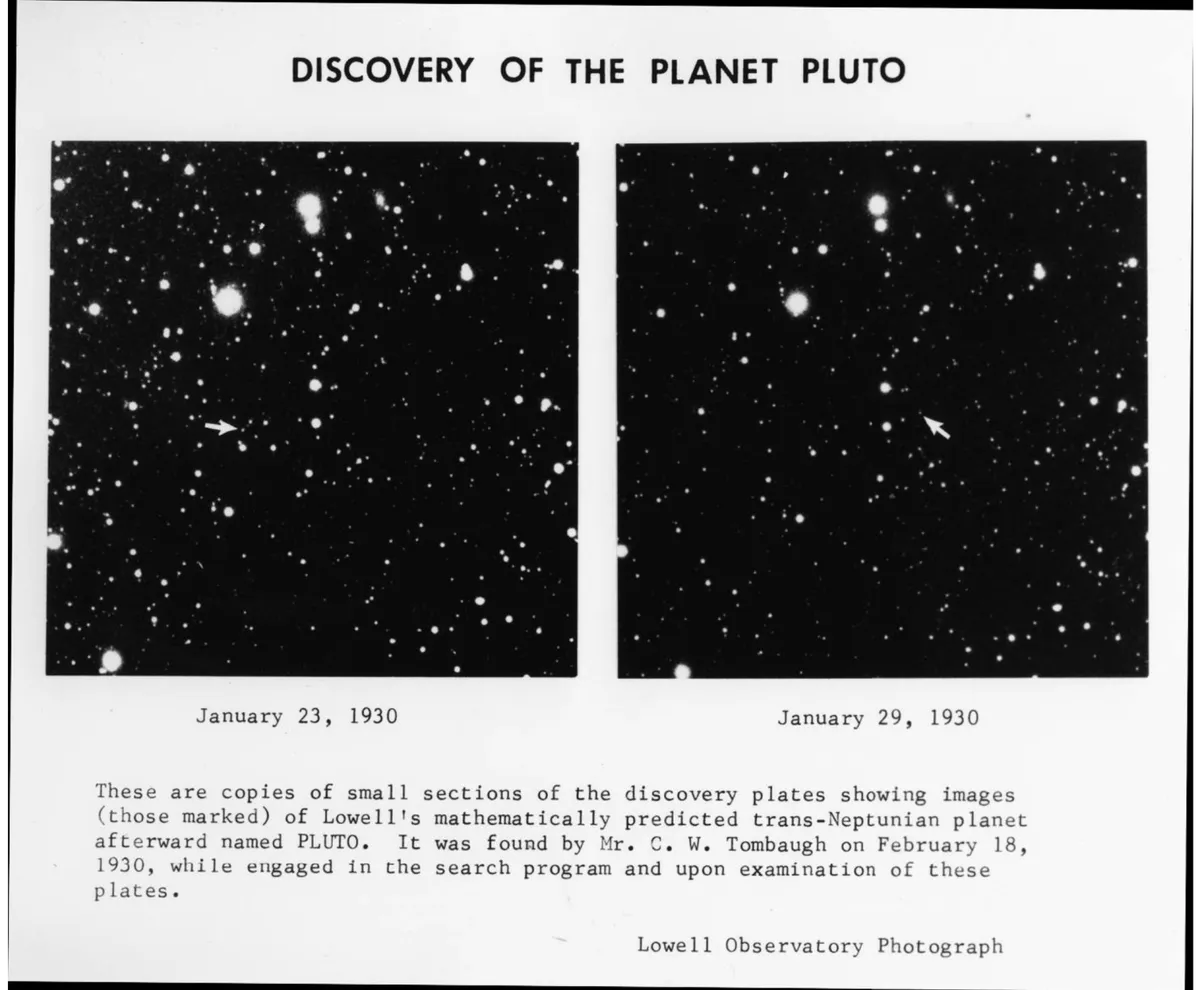

On 18 February 1930, Planet X revealed itself. Clyde Tombaugh spotted a small dot shifting in position across two astronomical plates taken earlier that year: a planet, subsequently named Pluto, moving along its orbit.

Astronomers had predicted that such a planet would be massive, at least as hefty as Earth, in order to push Uranus around the way it did.

But Pluto was small, dark and ringless. Its path around the Sun was highly elliptical, or oval-shaped, unlike the other planets of the Solar System.

Doubts immediately arose: could this tiny body really be a planet, or was it more like an asteroid, comet or even a moon?

The debate continued for decades, with research revising Pluto’s mass downwards (today, we know it to be just 1/500th the mass of Earth).

The surveys in the 2000s spotted more companions in Pluto’s vicinity: dwarf planets Haumea, Makemake and Eris, and dwarf planet candidates Orcus, Quaoar, Gongong and Sedna.

Many were comparable to Pluto in size, mass or distance. Eris, for instance (discovered in 2005), is more massive – heavier – than Pluto.

Sedna (discovered in 2003) is about 40% as big as Pluto and similar in brightness.

Quaoar (found in 2002) is half the size of Pluto and has a ring system, as does the 2004 discovery Haumea. Several of these worlds, like Pluto, have moons.

The discovery of substantial Eris was the beginning of the end for Pluto.

It was now unavoidable: Pluto didn’t appear to be the most massive object in that region of space, and certainly didn’t appear to be special.

In 2006, the International Astronomical Union (IAU), the authority on the definitions, characteristics and naming of bodies in the Solar System, issued their ruling.

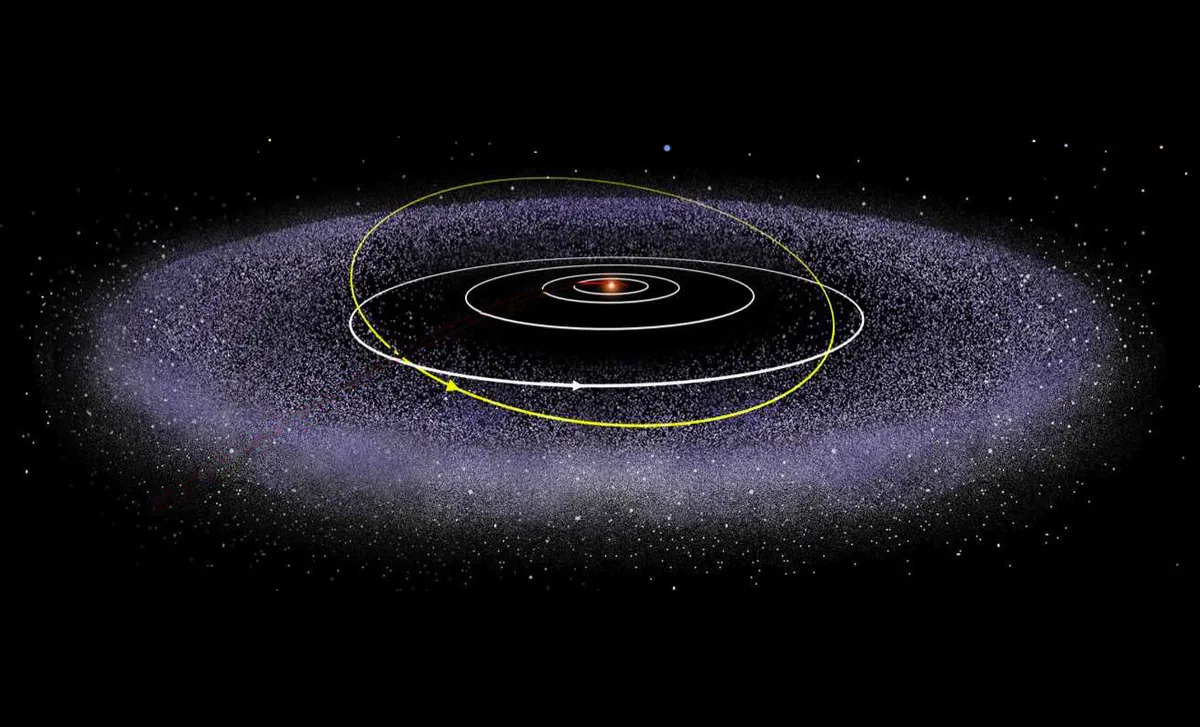

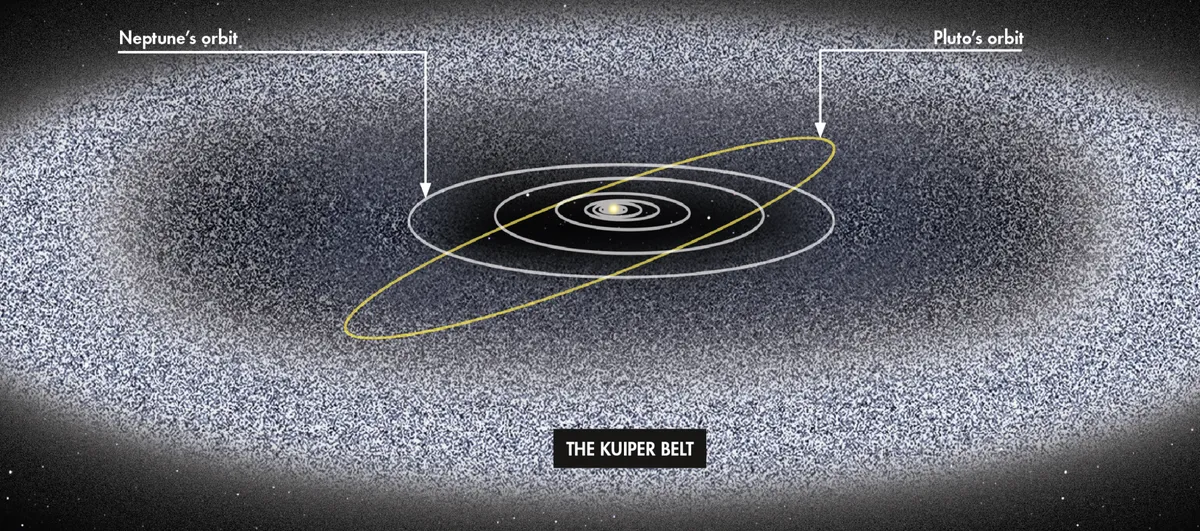

It decreed that Pluto was not a planet but a dwarf planet, just one of many such objects in that distant patch of space (a zone known as the Kuiper Belt).

Rather than being the Solar System’s smallest planet, it became instead the largest dwarf planet.

What makes a planet?

Planets take their name from their motion across the sky. The word ‘planet’ comes from the Greek ‘planētes asteres’ – ‘wandering stars’, or simply ‘wanderers’.

Over the years, astronomers have proposed many definitions of what it means to be a planet, based on factors such as mass, internal activity, roundness and whether it orbits a star.

In 2006, the IAU put forward its official definition, which is generally used – although not fully accepted by all astronomers – today.

To qualify as a planet in our Solar System, an object must:

- Orbit the Sun

- Be massive enough that its own gravity has pulled it into a roughly spherical shape

- Have cleared its neighbourhood of other comparable objects (gravitationally dominate its patch of space)

Pluto, while on track around the Sun and roughly round in shape, fell at the third hurdle.

Yet even this definition is far from clear-cut. Some argue that Earth and Jupiter technically have orbital neighbourhoods filled with asteroids and other rocky bodies, and that if Neptune had truly cleared its zone, then Pluto wouldn’t be where it is.

Others say the definition is too dependent on dynamics and not reliant enough on intrinsic properties of a possible planet.

Also, planets move more slowly the further they are from their star, so clearing a zone in the outer Solar System demands far more massive objects than in the inner regions.

This means an object that’s deemed a planet close to its star – like Earth – may no longer qualify as a planet if it lies further away.

This same problem could arise for two identical planets orbiting two very different stars.

Two new worlds: X and Y

As it turns out, no unseen planet was needed to explain the apparent irregularities that Lowell spotted in Uranus’s orbit.

After the launch of NASA’s Voyager space probes in the 1970s, we got better and better data, allowing us to recalculate the motions, masses and properties of the outer Solar System’s residents.

The culprit for Uranus’s odd movements? They weren’t in fact odd at all, and the planet’s main influence was Neptune all along.

While we don’t see a strangely moving Uranus, we do see other oddities – oddities that have led astronomers to propose more hidden planets.

In 2016, researchers at Caltech announced their belief in what they call Planet 9 (or sometimes Planet X), while a proposal for a Planet Y came from Princeton in 2025.

Both would reside in the Kuiper Belt, many billions of kilometres away, but would be very different worlds.

Planet 9 was proposed to explain a peculiar phenomenon out in the Kuiper Belt involving a group of six rocky, icy bodies found at more than 250 times the Earth–Sun distance.

According to Mike Brown and Konstantin Batygin of Caltech – the proposers of Planet 9 – the orbits of these objects seem to cluster together as they approach and swing around the Sun, a little like sheep sticking together as they’re shepherded.

This is highly unlikely given that each object is moving at a different rate, and their orbits all vary significantly as they head away from the Sun back out into more distant space.

Brown and colleagues put the chances of this clustering being false or coincidental at 1 in 500.

As Brown summarised in 2016, "it’s almost like having six hands on a clock all moving at different rates, and when you happen to look up, they’re all in exactly the same place. It shouldn’t happen randomly."

Planet Y, meanwhile, is distinct from Planet 9.

"They’re dynamically different hypotheses addressing different signals," says one of Planet Y’s proposers, Amir Siraj of Princeton.

Unlike Planet 9’s link to the apparent clustering of faraway worlds, Planet Y is connected to the tilt of the Kuiper Belt.

Roughly speaking, the ‘stuff’ of the Solar System aligns as a flat disc that encircles the Sun’s middle, like a giant belt.

This disc is the ‘orbital plane’ and is a consequence of how the system formed.

But head out as far as 80–400 times the Earth–Sun distance and ‘stuff’ begins to warp and skew, bending away from this plane.

Siraj says this odd lopsidedness can be explained by the presence of a planet.

"If a planet the mass of Mercury or Mars were lurking beyond Neptune on a tilted orbit, its steady gravitational tug would act on the Kuiper Belt like a small weight on the edge of a vinyl record, gently tilting the record away from the plane of the tabletop – or, in this analogy, the plane of the Solar System," adds Siraj.

"Without a continuous tug, any tilt would naturally dissipate in under 100 million years or so – so the fact that we see a warp suggests the existence of an active perturber."

Even more excitingly, it’s not a case of Planet 9 versus Planet Y.

"Both planets could exist,” says Siraj. “The two ideas are separate and could both be true."

A dose of scepticism

Despite the excitement of an outer Solar System filled with hidden planets, many astronomers remain unconvinced.

It’s quite possible that both the tilt of the Kuiper Belt and the apparent clustering could be artefacts of observation (especially as the clustering conclusion is drawn from just a handful of orbits).

"There may be a Planet 9 out there, but I doubt it’ll be one of the predicted versions of the planet," says Kat Volk of the Planetary Science Institute in Arizona.

"Many people are unconvinced by the evidence that has been presented for specific proposed planets.

"Personally, I’m not convinced the clustering is real at all. It could simply be a result of where surveys have looked, or to do with the dynamics of Neptune."

Ongoing research is continually changing our knowledge of what’s out there.

In 2017 and 2023, astronomers spotted icy bodies in the Kuiper Belt – named 2017 OF201 and 2023 KQ14 – that seemed to be shunning the influence of a shepherding planet: their orbits don’t cluster like the others.

In fact, if a Planet 9 did exist in the location proposed by Brown and Batygin, it would likely kick these objects out of the Solar System entirely.

Their discovery suggests that maybe there isn’t a Planet 9 – or that there once was, but it’s long since left our Solar System.

Our inventory of the bodies of the distant Kuiper Belt is far from complete.

It’s an extremely difficult patch of space to observe: even huge objects are very faint and slow, making them hard to spot.

Many follow wildly elliptical orbits, only coming close enough to be visible for a few fleeting moments before they disappear again.

While observationally frustrating, that fleeting visibility has another implication: that there are likely to be thousands of unseen objects out there that we simply haven’t spotted yet, just waiting to be discovered when they venture near enough.

"It’s not unlikely that there are large things out there that we haven’t detected yet," agrees Volk, "but the evidence for specific planets is mixed and not super high-quality. We need more data!"

Such data will come with the imminent switching-on of the Vera C Rubin Observatory, high on the summit of Cerro Pachón in the Andes, Chile.

This huge telescope will map the entire southern sky daily for a decade, is able to detect immensely faint light, and will feed new observations into a computer system that is constantly comparing them to older ones, allowing it to quickly spot changes in the sky – such as a moving planet.

It will be the largest digital camera on the planet. No other telescope on Earth is capable of spotting the faint glimmer of a possible Planet 9 or a Planet Y, but the Rubin Observatory will be able to see it as if it were Pluto: a pinprick out in the darkness.

Even if no planet is found, that doesn’t mean one doesn’t exist. Rubin will still "decisively confirm or refute the warp" of the Kuiper Belt, says Siraj, narrowing down our theories in the process.

It will also "dramatically increase the number of known distant objects beyond Neptune," adds Volk, and do so in a way that accounts for any observational biases.

"In a few years, we’ll have much better constraints on whether those orbits do or don’t show evidence of an unseen gravitational perturber."

So, how many planets are lurking out there in our Solar System? We don’t know, but we’re closer to an answer than ever before.