Planetary scientist Sarah Stewart Johnson is an expert on the exploration and study of Mars. Currently an assistant professor of planetary science at Georgetown University in Washington DC, Stewart Johnson has also worked on the science teams for the NASA Opportunity and Spirit Mars rovers.

Her research delves into Mars's ancient past, exploring whether or not the Red Planet may once have harboured life and whether signs of Martian life may be present today, awaiting discovery: something that NASA's new Perseverance rover will be investigating following its landing on 18 February 2021.

Stewart Johnson's new book The Sirens of Mars, published by Allen Lane, is an account of what we currently know about the Red Planet and a history of the observations and exploratory missions that have taught us all we know.

We got the chance to speak to her about what the prospect of life on Mars.

For how long have humans been exploring Mars?

Humans have been exploring Mars for thousands of years: first through the naked eye, charting its movements, then through telescopes. The beginning of the Space Age brought a quantum leap forward, with the first spacecraft reaching Mars in 1965.

Why is Mars such a promising place to look for life?

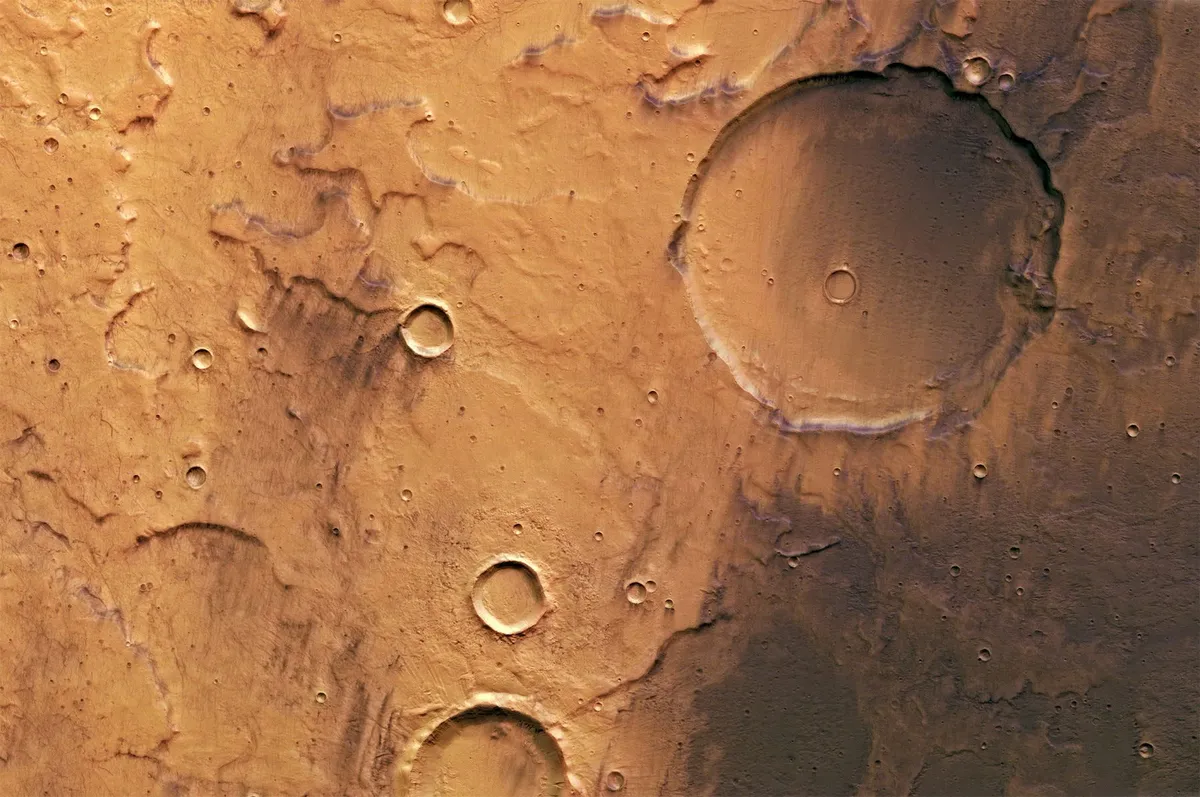

Of all the planets we know of, Mars is the most similar to Earth. Around the time life was getting started here, Mars was also warm and wet, at least episodically, with streams and lakes and perhaps a deep northern ocean.

There was a thicker atmosphere and a protective magnetic field, as well as abundant sources of energy.

As recent missions have shown, Mars also had all the right ingredients for life as we know it: the right chemical elements and organic building blocks.

But what excites me most is the idea of a separate genesis on Mars, which could mean we would find a kind of life that’s totally unlike life as we know it here on Earth. That would have enormous ramifications, scientifically and otherwise.

Designing tools and techniques to detect this kind of life - tools that don’t assume any specific underlying biochemistry - is a big focus of my lab’s research at the moment.

Who has contributed most to our understanding of the Red Planet?

There have been many extraordinary Mars scientists, including some widely known like Carl Sagan.

There were also the old timers like Christiaan Huygens, who made the first map of Mars, and then the greats of the early space age, like Bruce Murray (and of course Sagan).

Steve Squyres and John Grotzinger have led stunningly successful recent missions to Mars, and I think history will remember their contributions for a long, long time.

One of the biggest sources of inspiration to me was my own PhD advisor, Maria Zuber, who played a key role in mapping Mars, for the first time in exquisite resolution.

When I think about these individuals, one thing that really jumps out to me is how so many of them came from different walks of life and different fields of expertise.

In that way as in so many others, they reflect something important and unusual about planetary science, which is that it sits right at the nexus of disciplines like chemistry, biology, geology, physics and engineering, and therefore demands synthetic thinkers capable of unusual degrees of collaboration.

So many of these individuals have these qualities in spades.

Are we close to putting human feet on Mars?

Human missions are incredibly challenging, and there are huge hurdles still in the way, like designing ways to deal with the planet’s harsh surface radiation.

But the leap from never having been to space in 1957, when Sputnik launched, to landing on the Moon in 1969 seems to me a much harder leap than what it would take to go from our current capabilities to a human Mars landing.

The landscape is also changing very rapidly, with many nations creating and growing space programs and the increasing involvement of the private sector.Never before have so many resources been invested in Mars exploration.

I don’t know what the coming years will bring, but I do think the stage is set for rapid progress if we decide we want to do it.

If there were a human mission to Mars launching tomorrow, would you go?

I spent most of my 20s hoping to apply to NASA’s astronaut program. Had the opportunity presented itself, I wouldn’t have hesitated.

However, I now have two little kids, and Mars would simply be too long a journey.For context, whereas the Moon would be like a business trip, 3 days there, 3 days back, a trip to Mars with current technology would be a 2.5-year endeavour, requiring 6 months’ travel each way plus a year and a half waiting on the surface for the planets to realign on the same side of the Sun.

So, as much as I love exploring the ends of the Earth, and as much as I dream about space, the honest answer is that I could not bear such a long separation.

There are no second chances with kids, and I don’t want to miss a thing.

Sirens of Mars: a review

Words: Dr Hannah Wakeford

Surely there is life on Mars – or at least that is what was thought by astronomers from the late 1600s all the way up to the 1980s. But in recent years that statement has taken on a whole new meaning.

This book takes us on a voyage through our relationship with the Red Planet and makes us appreciate the tremendous journey it has made in the popular zeitgeist, from a world covered in carefully engineered canals for advanced alien inhabitants, to a lush vegetated haven and finally to the cold, ancient and desolate wasteland we know today.

Looking behind the scenes of life as a modern planetary scientist, The Sirens of Mars follows the author’s experiences of the lows and highs of many of the most celebrated Mars missions.

The linear timeline of exploration helps to anchor Sarah Stewart Johnson’s story to the big question of “Is there life on Mars?”.

We follow along with her as she realises the implications of highly acidic material uncovered by Opportunity, sit with her in the Mojave Desert mapping the landscape of alien terrain on Earth, and sympathise with the feeling of isolation and separation from the world as she adjusts to ‘Martian time’ in the control room at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, monitoring rovers on a distant world.

In many places you will rush to the internet to look up the images and maps described in the book to understand Johnson’s wonder at the discoveries being made.

The book would have greatly benefited from including some of these: the original pictures and charts of Mars used to design the Mariner missions that now sit on the author’s office wall, the first image from Opportunity as it approached the precipice of Endurance crater, the Olympic Rings etched forever into the Martian rock by the Spirit rover.

Some are easy to find and some impossible, but each is pivotal to the author’s, and the reader’s, relationship with Mars.

Although at times not the easiest to follow, this is a must-read for fans of our Martian neighbour and humanity’s longstanding search for life elsewhere in the Universe.

Iain Todd is BBC Sky at Night Magazine's Staff Writer.

Dr Hannah Wakeford is an astrophysicist at the University of Bristol where she studies exoplanets using the Hubble Space Telescope.

This review and interview originally appeared in the July 2020 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.

Read more: