The 2025 summer solstice fell on 21 June at 03.42 BST (02.42 UTC), marking the first day of summer.

For those of us in the Northern Hemisphere, we marked the summer solstice on that date (whereas our friends south of the equator marked their winter solstice).

As you probably know, the summer and winter solstices are the longest and shortest days of the year, respectively.

But what does the word actually mean, why do we have solstices, and what implications does the solstice have, both for astronomers and for society at large?

What does 'solstice' mean?

‘Solstice’ comes from the combination of the Latin words ‘sol’ (the Sun) and ‘sistere’, which means ‘to stand still’.

The Sun doesn’t actually stand still, of course, but the solstices fall when the Sun ceases its apparent movement northwards or southwards that’s been ongoing since the last one.

Why solstices happen

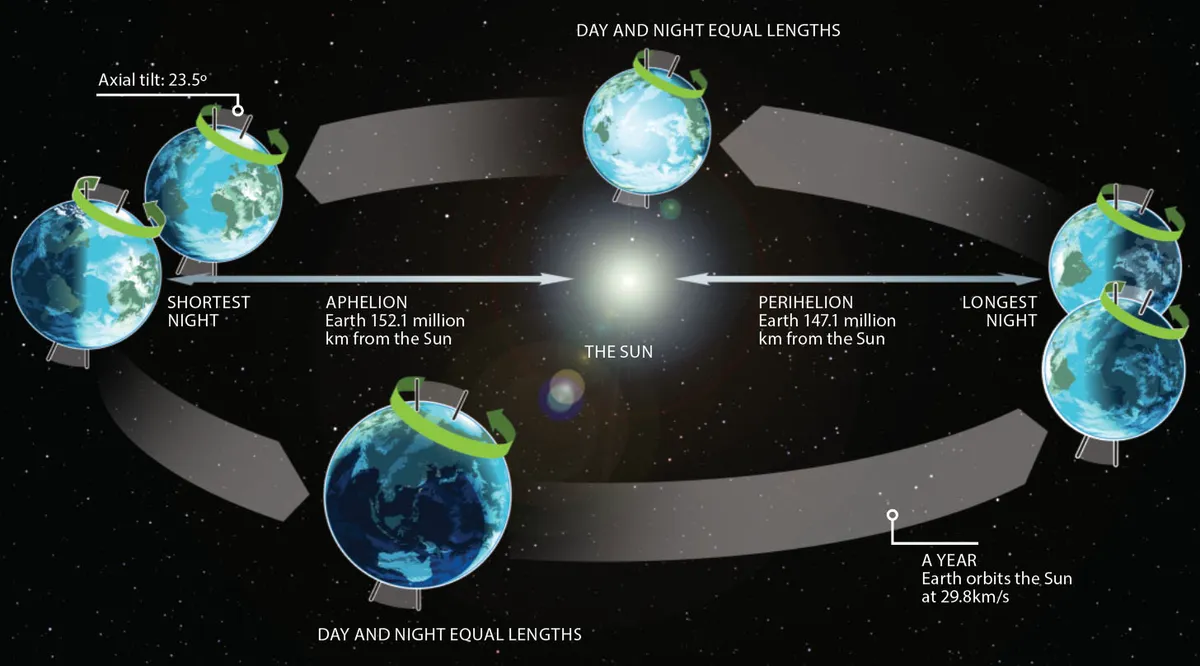

As for why solstices happen, it’s all to do with Earth's orbit around the Sun and its axial tilt; its physical inclination relative to its orbital plane.

If Earth sat bolt upright, with a line between the poles forming a right angle to the planet’s orbital path around the Sun, then everywhere on Earth would receive the same amount of sunlight all year round.

The Sun would rise and set in the same position all year, and there would be no such thing as seasons.

But Earth doesn’t sit bolt upright. Instead, it’s inclined at an angle of around 23.5°, relative to its orbit around the Sun.

This means the Northern and Southern hemispheres each spend six months of the year leaning towards the Sun, and six months leaning away from it.

As a result, the Northern Hemisphere gets the most Sun (and experiences its longest days) in the months of June, July and August, which we call ‘summer’.

At the same time, the Southern Hemisphere is getting far less Sun and daylight, so it’s ‘winter’ there.

And vice versa in November/December/January.

This effect is more noticeable the closer you get to the poles, with the North Pole (and in fact the whole of the Arctic Circle) getting 24 hours of daylight at the summer solstice and 24 hours of darkness at the winter one, again with the reverse being true at the South Pole and in the Antarctic Circle.

Solstice and sunrise

Another consequence of Earth’s inclination is that, from the Northern Hemisphere, the Sun appears to rise and set a little further to the north every day from the winter solstice until the summer one.

Then it reverses direction and rises/sets a little further to the south every day until the winter solstice, when the cycle begins afresh.

That turnaround occurs at the solstice, when the Sun appears to remain stationary for a day or two: hence the name.

Why the solstice changes date

Because Earth’s orbit is elliptical rather than circular, the date when solstices occur can vary.

The Northern Hemisphere’s summer solstice is always on 20, 21 or 22 June, while its winter solstice always occurs on 20, 21, 22 or 23 December.

Why they're important

For astronomers, the most obvious implication of the solstice and the changing length of nighttime and daytime is that shorter nights mean less time available for gazing at the stars.

But solstices also have other uses.

For instance, from studying when they occur(ed) we can detect and measure any changes in Earth’s orbit or tilt over longer timescales.

As for society more generally: once upon a time, before we had accurate clocks, solstices and equinoxes were our only truly reliable means of tracking the passage of time.

So it’s unsurprising that they’ve been celebrated in many cultures worldwide for as long as we can remember.

Which is why many ancient monuments, such as Stonehenge and the Great Pyramids of Giza, appear to have been built to line up with the Sun at these key times of the year.

2025 summer solstice

In 2025, the summer solstice occurs on 21 June.

Perhaps you’ll be one of the many thousands making a pilgrimage to Salisbury Plain, to partake in some all-night pagan revelry around the ancient stones.

Perhaps you’ll spend the daytime in your backyard observatory, taking advantage of the long hours of sunlight to test-drive the more advanced features on your new solarscope.

Or perhaps you’ll just be basking in the midsummer sunshine.

But whatever you do – enjoy it, because it’s another opportunity to reflect on what a complex, interlocking machine our Solar System really is.