When astronomers survey bright stars that have the same mass as our Sun or greater, they find that most have at least one companion.

Stellar singletons like our Sun are the exception to the rule. So what made our local star a loner?

More solar science

Why stars seem to stick together

Thanks to gravity working on a variety of scales, stars are naturally gregarious.

They’re born in their hundreds or thousands inside collapsing clouds of gas and dust, and spend their early lives huddled together as star clusters that take millions of years to drift apart (and sometimes never do).

Many stars remain bound for life on a closer level, as binaries or multiple-star systems, whose individual members orbit a shared centre of gravity.

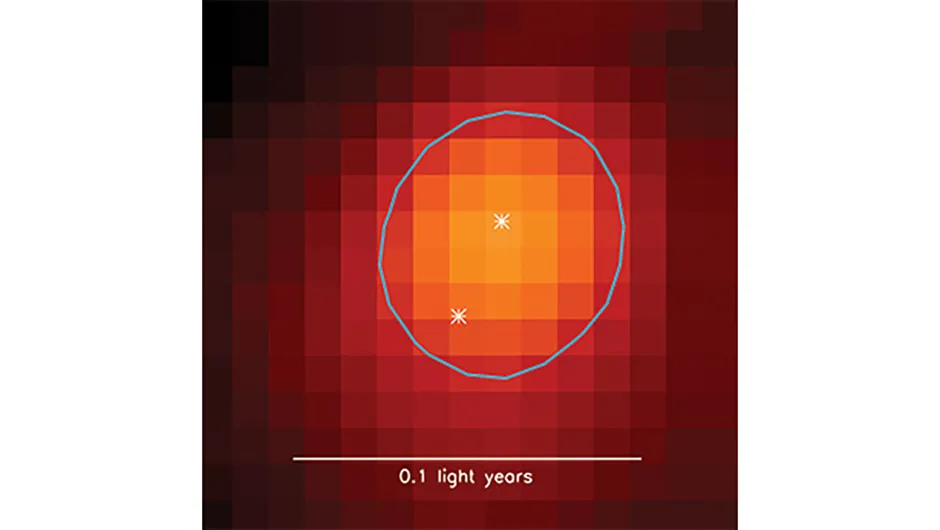

Telescopes can only pick out the individual stars in such multi-star systems if they’re particularly near to us or widely spaced, but there are clues that reveal their true abundance in the Universe.

These range from regular dips in a system’s combined light when one star eclipses another, to shifts in the wavelengths of light as orbiting stars move towards and away from Earth.

By some counts, up to 85% of all broadly Sun-like stars have at least one companion.

Why our Sun is in a distinct minority is one of astronomy’s most intriguing questions.

Recent research points to some surprising answers to do with the environment in which stars are born and spend their early years.

Why binary stars are so common

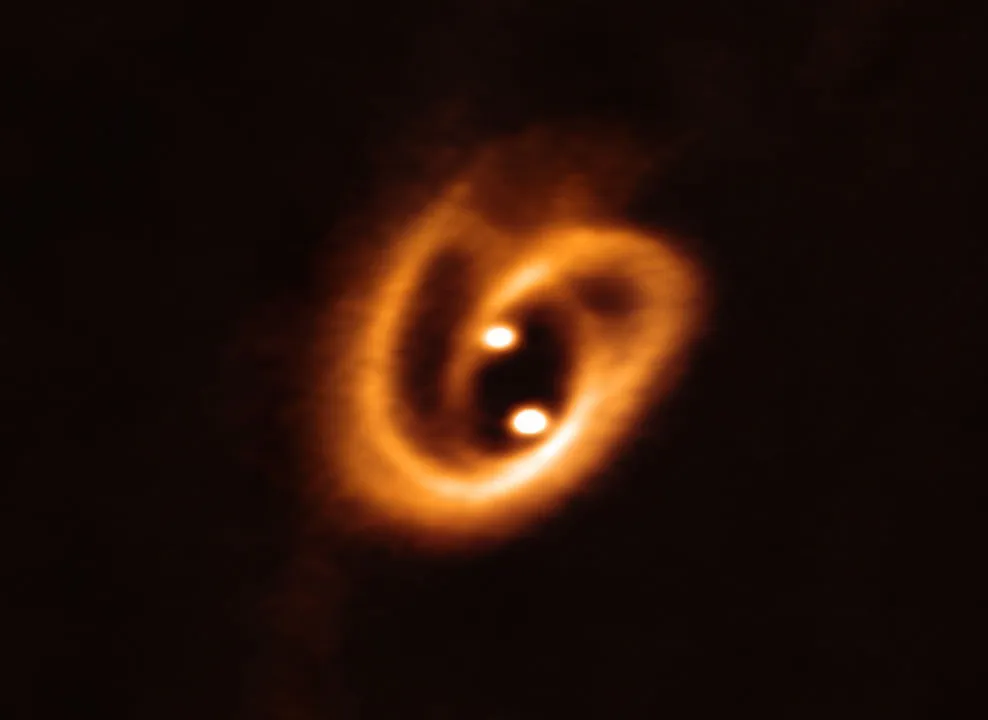

Star birth involves star-forming nebulae fragmenting into pillars, tendrils and finally globules of gas and dust.

Inside these opaque cocoons, the densest regions exert more gravity and so pull in more gas, growing ever denser and hotter until they eventually start to shine.

As the dust clears and newborn stars emerge, they’re often already grouped in binaries and multiples, so astronomers are confident this is how most stellar systems begin – with two or more distinct collapsing regions inside a single globule.

To understand what’s happening inside these globules, astronomers use radio and infrared telescopes to detect radiation passing through the veil of dust, alongside sophisticated computer simulations.

Evidence from both techniques suggests that stars first form in ‘wide’ binaries, separated by distances greater than the diameter of the Solar System.

From this point, some systems spiral inwards to form a tighter group, while a few remain wide apart.

A substantial fraction, however, are split apart by chance encounters with other stars, sending each member of the system drifting away on new solo trajectories.

Based on the likelihood of such gravitational disruptions, estimates suggest that about 40% of all solo Sun-like stars may have been exiled from a pair or a system in this way.

However, some computer models suggest that almost every globule of primordial gas and dust should produce at least two stars, making disruptions even more common.

The Sun’s solo story

Whichever is correct, it seems very likely that our Sun was indeed once part of a larger system, with its long-lost siblings still orbiting somewhere in the Milky Way.

If confirmed, this could tell us something important about our own story and the prospects for life elsewhere in our Galaxy.

The wide separation of sibling stars during formation should have allowed room for planets to form from the discs of material around them, but the inward spiral to form a tighter system would almost certainly eject such worlds from their stable orbits.

It could be that our Solar System only survived to produce life because an ancient chance encounter pulled the Sun away from its siblings.

So perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised that our Sun is alone – that very isolation may have been essential for life to emerge on Earth.

Are most stars really in pairs and multiple systems? Astronomers aren’t sure, because the answer depends on red dwarfs – the faint, hard-to-study stars that vastly outnumber Sun-like ones.

Current estimates suggest about 50–60% of red dwarfs are single, which could make solo stars the true majority.

The red dwarf dilemma

So why are so many red dwarfs loners? One reason could be that the low mass and weak gravity of red dwarf systems makes them more prone to disruption.

Another is that smaller gas and dust globules are less likely to split into multiple star-forming cores in the first place.

Star formation tends to proceed in a hierarchy, with the most massive stars in a new collapsing nebula forming first.

As they emerge from their cocoons, powerful radiation and strong stellar winds from these young monster stars (far brighter than the Sun) blast away material from their surroundings, creating shockwaves that trigger further star birth – but also stripping away material for later generations of stars.

By the time small globules are creating red dwarfs towards the end of this process, it could be that a combination of weak gravity and a depleted surrounding environment makes them more likely to collapse into a solo star.