Finding out how star formation stops is one of the biggest problems in astrophysics.

On average, as the Universe ages, galaxies shift from being rich in star formation, lit up by the brilliant blue light of massive new stars, to quiescent, quiet places.

The process is known as quenching, but a study making use of data from the Hubble Space Telescope suggests that quenched galaxies might not be as dead and dull as previously thought.

Led by Michael Rutkowski in Minnesota, the authors have identified what we might call ‘zombie galaxies’, quenched but still undergoing sporadic and really quite significant bursts of star formation.

The galaxies in question are among the most massive in the Universe, exactly the type we’d expect to have stopped forming stars long ago.

From objects included in the UVCANDELS survey (Ultraviolet Imaging of the Cosmic Assembly Near-infrared Deep Extragalactic Legacy Survey Fields), one of many deep imaging surveys undertaken by Hubble in recent years, the team picked galaxies with a stellar mass greater than 10 billion times that of the Sun, and which showed no signs of active black holes (to avoid contamination of their final sample).

Signs of life

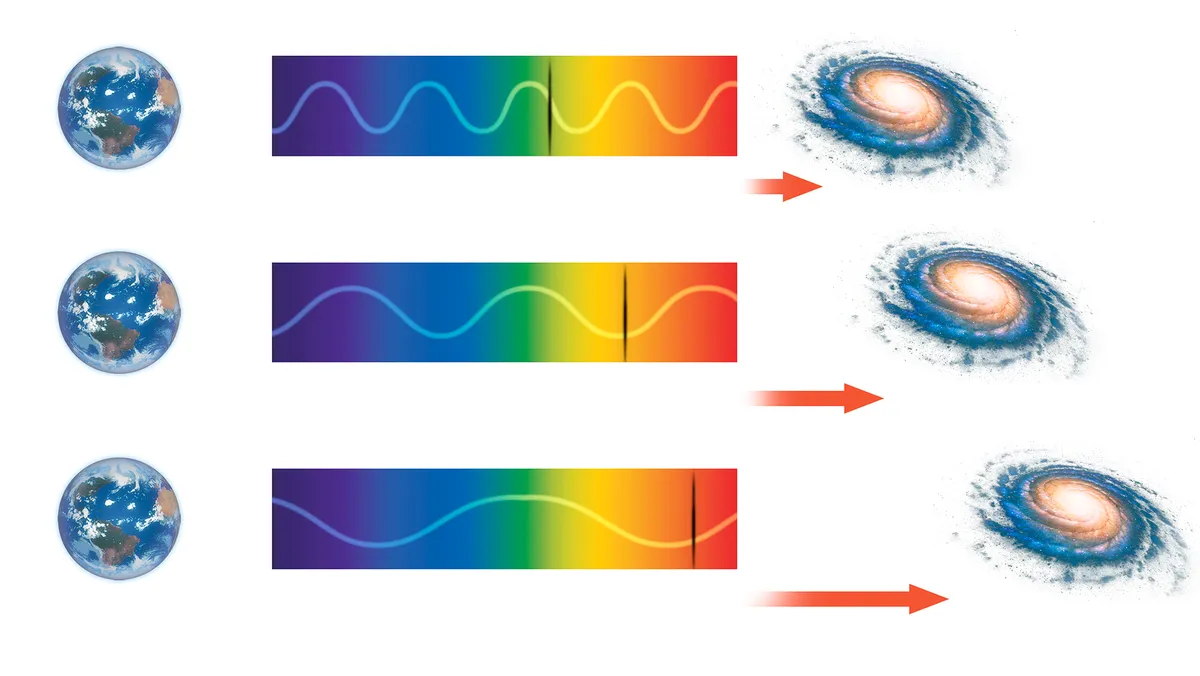

The redshifts of the galaxies lie between 0.5 and 1.5, so we’re looking back 5–9 billion years, from the time just after the cosmic rate of star formation peaked.

The 1,067 galaxies remaining in the sample look like the big, boring ellipticals that one would expect to have ceased star formation early.

In the local Universe, it’s spiral galaxies that host most stellar nurseries.

What’s interesting is that the team have ultraviolet observations for these galaxies.

Brilliant, massive young stars which only live for a short while once formed, shine brightly in this part of the spectrum.

That means that ultraviolet light can be used to trace hidden star formation, which is what the team did.

Within the sample, 15% were bright enough for the team to surmise these seemingly dead-looking galaxies had undergone a recent burst of star formation, forming no more than 10% of their stars in the last billion years.

For a massive galaxy, even a few per cent represents a substantial episode of star formation. The zombie galaxy, newly revived, lurches on.

How can galaxies come back to life?

One plausible explanation for their rejuvenation is that we’re seeing the result of galaxy mergers.

Consuming a younger system provides a fresh transfusion of gas from which stars can be made.

This hypothesis, more vampire than zombie, is, however, ruled out by the absence of a link between how dense an environment a galaxy lives in and the odds of it having recent star formation.

Mergers happen more in denser environments, so we should see a strong connection if they’re responsible.

What’s really happening must be stranger, some internal process that we don’t yet have a handle on.

It’s possible that the black holes at the centre of the galaxies, in a quiet mode so their growth is not easily spotted, may be having an effect.

Plans are already being made for better images and spectra of these intriguing systems.

After all, everyone loves a zombie movie, don’t they?

Chris Lintott was reading Recent Star Formation in 0.5<z<1.5 Quiescent Galaxies by Michael J Rutkowski et al. Read it online at: arxiv.org/abs/2504.05511.

This article appeared in the June 2025 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine