The Cassini Crater is an example of a ring plain crater, a narrow rim enclosing a relatively flat floor area (aside from some obvious exceptions).

The rim is complete all the way round and rises to around 1.2km high, decreasing to 460m on the eastern side.

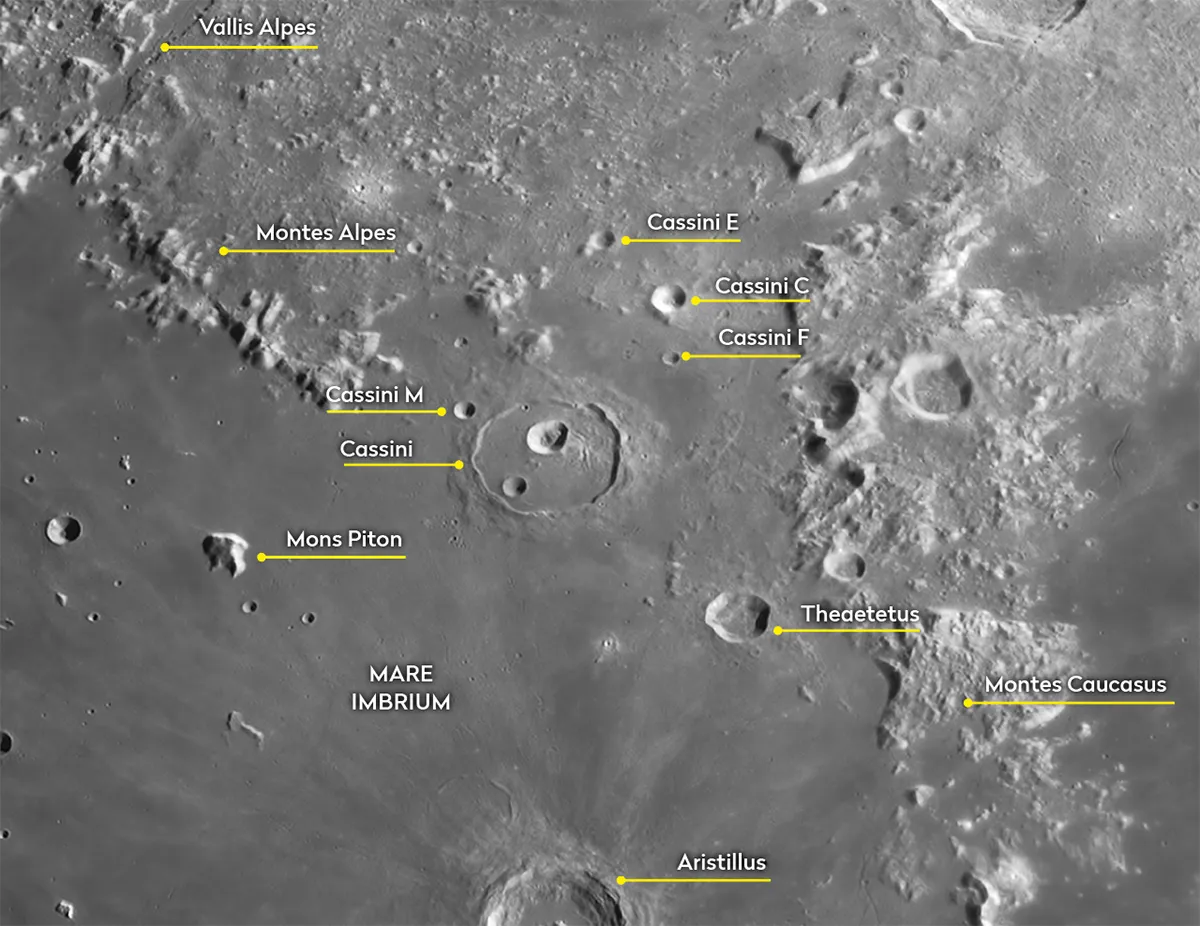

The whole structure is surrounded by a rather impressive ejecta rampart, a very obvious feature as the Cassini Crater sits on the flat northeast lava surface of 1,250km Mare Imbrium.

Crater Cassini quick facts

- Size: 58km

- Longitude/latitude: 4.7° E, 40.3° N

- Age: 3.8–3.9 billion years

- Best time to see: First quarter or six days after full Moon

- Minimum equipment: 50mm refractor

For more advice, read our guide on how to observe the Moon, how to measure craters on the Moon and a complete list of lunar maria

Cassini A

The most prominent of those ‘obvious exceptions’ on Cassini’s flat floor is the elongated form of the 17km bowl-shaped crater Cassini A, its linear size being 29% that of Cassini itself.

The crater appears mostly circular, but with an obvious extension to the east creating a pear shape.

The floor of Cassini A appears to contain a series of narrow ridges.

The lunar observers Percy Wilkins and Patrick Moore, using the 33-inch Meudon refractor in Paris on 3 April 1952, describe how the base of Cassini has a "white, very shallow crater within which is a most minute central pit."

As a result, they proposed calling the feature the Washbowl, an informal name that some amateurs continue to use today.

Modern analysis of the feature suggests it’s not a crater at all, but possibly a trick of the light when the original observation was made.

Cassini A is also notable because of the grooves that can be seen within the hilly area to the east and southeast of it.

These are fascinating to observe when light falls obliquely on Cassini.

Cassini B

Another ‘obvious exception’ comes in the form of 9.4km Cassini B.

Unlike Cassini A, Cassini B really does have the appearance of a circular crater and also has the classic bowl-shape. It sits close to Cassini’s southwest rim.

Under oblique lighting it should be possible to detect the presence of three hills located between Cassini A and B.

There’s a third 2.4km craterlet present on Cassini’s floor, located further north, that appears to be touching Cassini’s northern rim.

Looking at the bigger picture, Cassini is fortuitously positioned in a relatively flat area between Montes Alpes to the northwest and Montes Caucasus to the southeast.

These dramatic ranges provide excellent framing for the crater.

Many of the smaller craters to the east are designated satellites of Cassini, the most notable being 13.8km Cassini C which originally had its own name, being known as Zinger.

The International Astronomical Union (IAU) relocated that name to a far-side crater, now known as Tsinger.

Heading west across the flat lava of Mare Imbrium, it’s not mountain ranges that dominate but rather a singular mountain called Mons Piton.

This is best seen like Cassini, at first quarter or six days after full Moon and is most impressive.

Read our guide to find out when the next full Moon is visible.

Its form can be contained within a circle of 25km diameter, the mountain peak rising to a height of 2.25km.

Its most impressive trick is to create a dramatic pointed shadow that is beautifully projected across Imbrium’s floor when the morning or evening Sun is low in the mountain’s sky.

This article appeared in the December 2023 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.