There's a misconception that if you want to get into stargazing you have to spend money on high-tech equipment such as Go-To telescopes and CCD cameras.

What if you just want to start with very basic astronomy and don’t want to buy anything? What can you see just by stepping outside and looking up?

Here, we'll take you on a first night’s tour of the night sky and reveal how to stargaze in 10 easy steps…

For more advice, read our guides to astronomy for beginners, the best telescopes for beginners and the best telescopes for kids.

And find out what's in the night sky each week by signing up to receive the BBC Sky at Night Magazine e-newsletter and listening to our Star Diary podcast

Read beginners' books and online resources

There is a wealth of astronomy books and websites dedicated to observing the night sky, and if you want to get started in stargazing but are facing a week of cloudy, rainy weather, why not begin by learning the basics in theory?

Practical astronomy books for beginners will teach you the basics of stargazing: what you can expect to see in the night sky at certain points of year, how to get started observing the Moon, and which stars and constellations are most prominent throughout the seasons.

You can get started by browsing our pick of the best space and astronomy books and best space and astronomy audiobooks.

Wrap up warm

Before you even look at the sky, take a look at yourself in the mirror. Are you dressed properly?

You’re going to be outside for at least an hour, hopefully longer, so dress appropriately for the cold, with a warm jacket, thick socks, gloves, scarf and a hat.

Basically, you want to look like one of the rosy-cheeked children playing happily in the winter snow from a vintage Ladybird book.

Choose your stargazing site

If you’re lucky you’ll be able to stargaze from your back garden, but it might not be the ideal place. Your garden could be surrounded by other houses, tall buildings and trees, which all reduce the amount of sky you can see.

And light pollution coming from nearby streetlights, pubs, shops and factories, and neighbours’ security lights can take even more of your view away.

If this is the case, get away from all that. Head out of town to a dark spot in the countryside. There are many amazing places to stargaze in the UK and places to stargaze in the USA.

But you could even just walk around the corner to your local park or school playing field. It’ll make a big difference to what you can see.

Let your eyes adapt to darkness

Once you’ve found your observing site, you’ll need to give your eyes time to get used to the darkness.

Astronomers call this process ‘dark adaptation’ and it takes about half an hour.

After your eyes have relaxed, opened up their pupils to take account of the reduced light levels and released special chemicals to enhance their sensitivity, you won’t believe how many more stars you can see than when you first arrived.

Don’t browse on your phone while you wait; its bright screen will ruin your night vision. But turning your screen red will help preserve your dark adaption.

For more help with this, find out how to turn your iPhone screen red or read our guide to averted vision.

Take time to observe individual stars

Eyes successfully dark-adapted, you’ll notice that the sky is full of stars, many more than you see with just a glance from a light-polluted site.

You’ll realise that some stars are brighter than others.

Every star is a distant Sun and they are all different distances away from us. So a bright star is just closer to us than a faint star, right?

Well it’s not quite that simple. Like light bulbs, some stars are brighter and more powerful than others.

So just because a star is faint in the sky it doesn’t mean it’s a low power one; it might be a very luminous star a great distance from us. Likewise, a bright star in the sky might be a weak star that’s close.

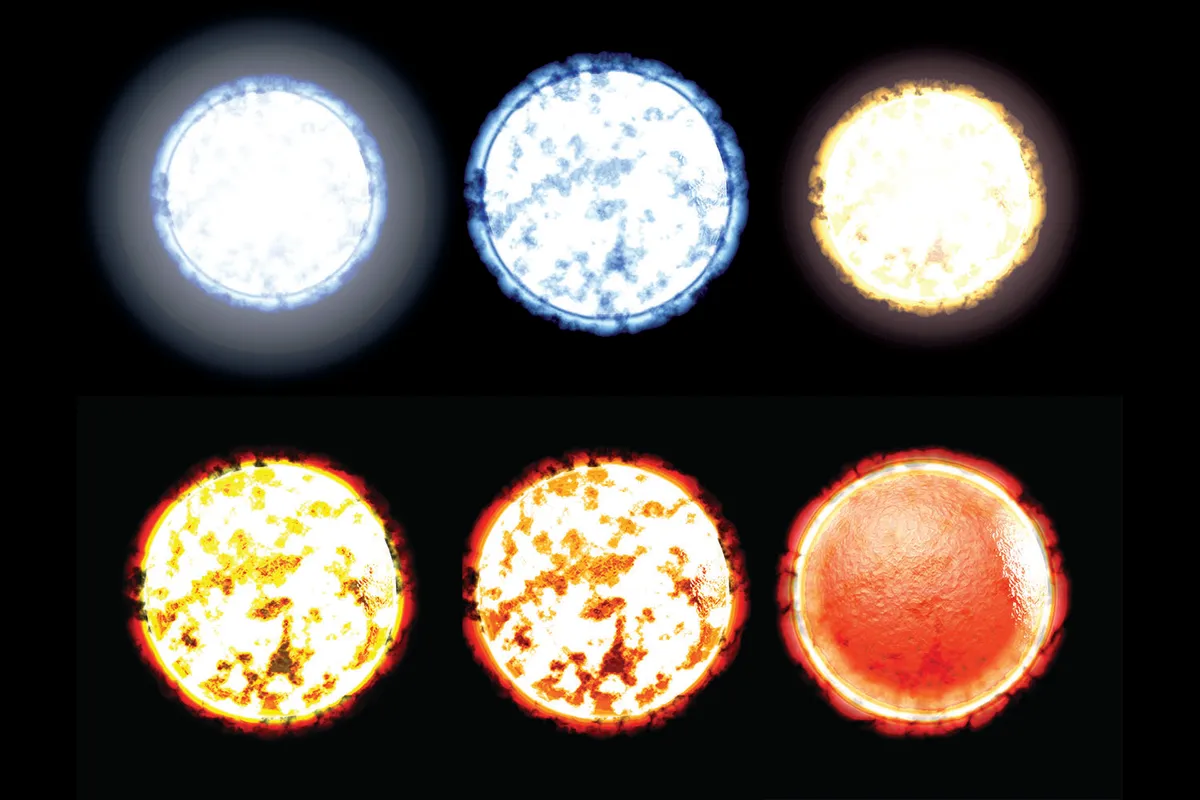

You’ll see differences in the stars’ colours too. Most stars are an icy white colour, but after dark adapting your eyes you will make out that some are more of a bluish colour while others are yellow, orange or even red.

This is because stars have different temperatures. Blue stars are much hotter than orange stars, which makes sense if you consider the difference between a warm yellow candle flame and the fierce blue flame of a blow torch.

Stars aren’t just different brightnesses and colours. Some are smaller than our Sun, others are much larger, but those differences aren’t apparent to our naked eyes.

Learn the constellations and asterisms

Once you’re dark-adapted it won’t take you long to notice that the stars can be joined up to form patterns. You might recognise one straight away.

You may be able to see the giant saucepan-shaped Plough, balanced on the end of its handle.

But the Plough isn’t a constellation – it’s an asterism, a small pattern of stars immediately obvious to the naked eye, but which isn't one of the 88 formally recognised constellations.

The Plough forms part of the constellation of Ursa Major, the Great Bear. The Plough’s handle represents the bear’s tail, and fainter stars around it form the bear’s legs and head.

There are 88 constellations in the sky, but very few look like the person, animal or object they represent. You need a lot of imagination to recognise most of them!

You can use constellations and their stars to star-hop around the night sky, like, for example, learning how to find the North Star.

Orion is a good constellation to get to know, as it's best seen in the winter months when skies are darker.

Also, Orion is a good starting point to jump to Sirius, the brightest star in the night sky, the Pleiades open star cluster (which looks great through binoculars), and the twin stars Castor and Pollux of the constellation Gemini.

Spot the planets with your naked eye

You can see all the planets out to and including Saturn with your eyes alone, although they’re not all visible at the same time.

To the eye Venus is by far the brightest and fairest planet, shining like a beacon in the east when it’s the ‘Morning Star’ before sunrise, or in the west when it’s the ‘Evening Star’ after sunset.

How can you tell which bright stars are actually planets? There’s an easy way to tell them apart: stars twinkle, planets don’t.

This is because while stars are points of light, planets are tiny discs, so stars are affected more by the movement of the air, providing an answer to that oft-asked question 'why do stars twinkle?'

The twinkling effect is something you can capture in a photograph showing the changing colours of a star.

If you see a bright ‘star’ that isn’t twinkling, it’s almost certainly a planet. You can confirm this by working out whether your 'planet' is located along the ecliptic.

However, you should make sure that there are actually bright planets visible in the night sky at the time of your stargazing session.

Planets aren't always visible, and they don't appear in the same place at the same time every year the way the stars and constellations do.

Online resources and stargazing apps will help you find out whether there's a bright planet like Venus, Mars or Jupiter visible.

Observe a meteor shower

After a while you will almost certainly see a star dash across the sky: a meteor, or shooting star! These are tiny grains of space dust burning up in the atmosphere.

Very bright ones, called fireballs, can drop meteorites on the ground.

The good news is there are annual events known as meteor showers that occur at the same time every year.

Some are better than others, with the Perseid Meteor Shower and the Geminid Meteor Shower being among the best.

But the quality of a meteor shower also depends on what the Moon is doing: if the Moon is full and bright during a shower's peak activity, its brightness will reduce the number of many meteors you can see.

Meteor showers are best seen with the naked eye and in groups, making them ideal starting points for beginners, young astronomers and families.

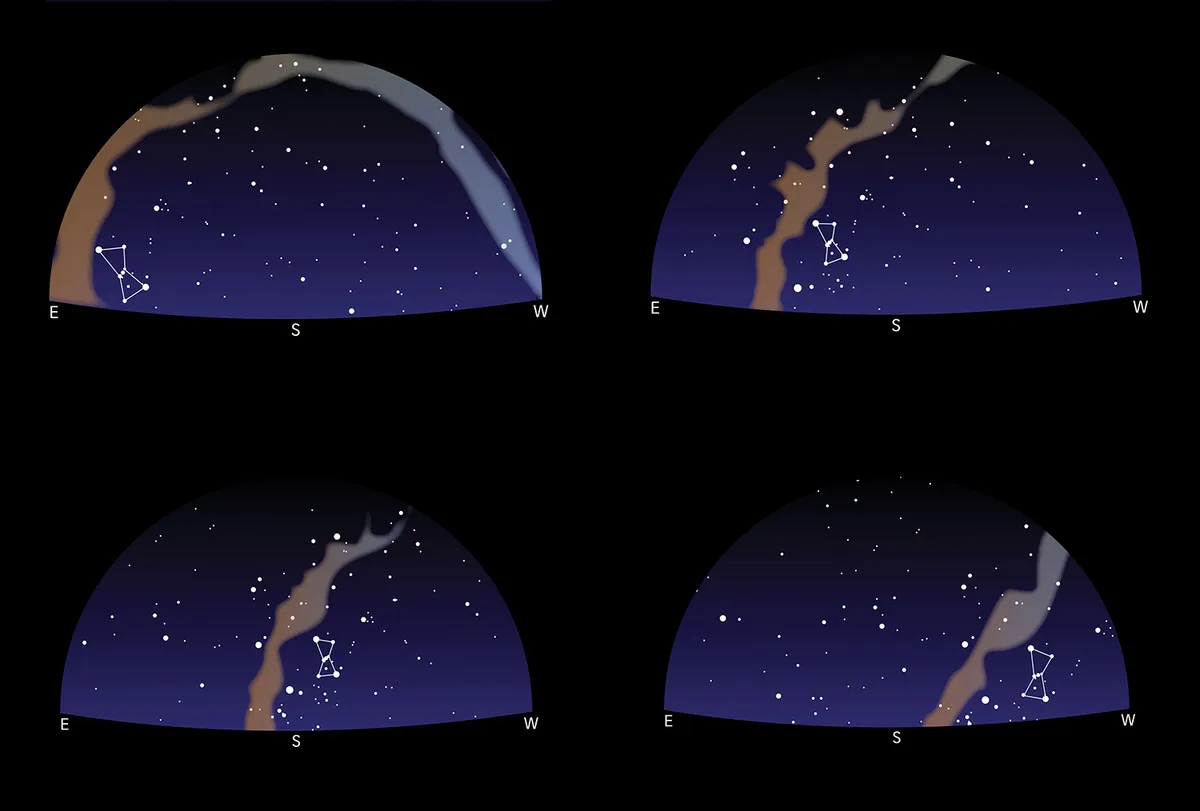

See how the stars move across the sky

If you stay at your observing site long enough you’ll notice that the stars which were low in the east when you arrived have climbed higher in the sky, and those which were low in the west are lower or might even have vanished from view altogether.

Why? It’s because as Earth rotates the stars appear to sweep across the sky. This effect is often captured by astrophotographers and is known as star trails.

If you're interested in mathematics and the motion of the sky, there's an interesting experiment you might like to try out, in the form of calculating the speed of Earth's rotation by observing the night sky.

Only one star stays relatively still: Polaris, the Pole Star, which is aligned with Earth’s axis and can be found using the ‘Pointer’ stars in the Plough.

Return to your observing site in August or September and you’ll see the whole sky has changed. This is because the constellations we see change during the year, as Earth orbits the Sun.

Each season has its own constellations, which is why it takes a year to properly learn the sky and not just one night.

However, there are circumpolar constellations that are always visible in the sky, and it's worth learning these as they are a good reference point as to how the sky changes throughout the year.

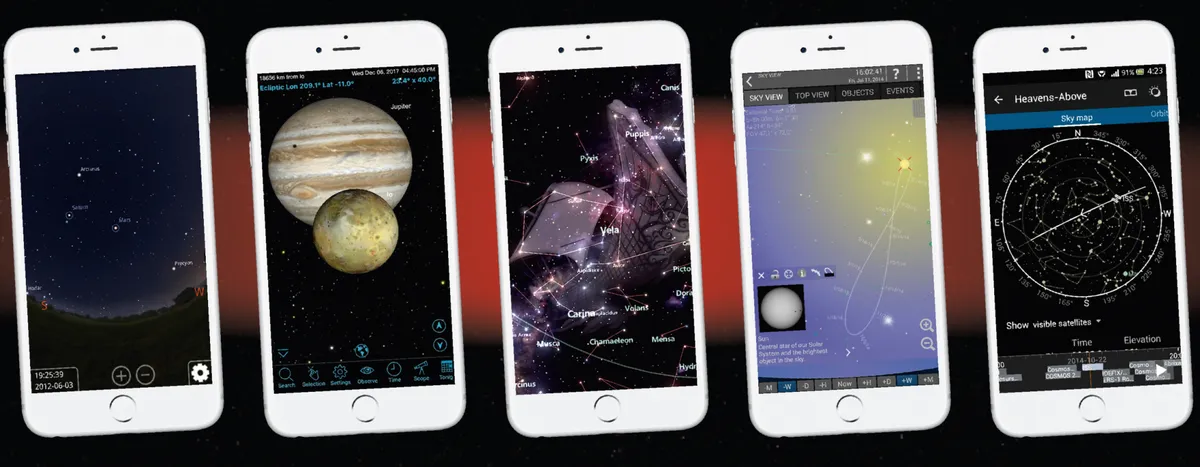

Use stargazing apps

There are many stargazing apps for your smartphone or tablet that will help you instantly locate stars, planets, constellations and deep-sky objects.

Here are five planetarium apps that will help you around the night sky, but you'll find plenty more in your app store. Turn your screen brightness right down or make it red to keep your night vision!

Five stargazing apps

- Stellarium Mobile Free: It’s missing the whistles and bells found on other apps, but Stellarium’s simulation of the night sky is beautifully realistic and gives a true impression of what the sky looks like.

- SkySafari:The free version of this feature-packed planetarium app gives you all the information you need to plan your observing sessions, and enjoy eclipses and other astronomical events.

- Star Tracker: A basic app that will help you identify stars, constellations and planets as you sweep your phone or tablet around the night sky. Beautiful graphics, but slightly annoying music.

- Mobile Observatory Free: A powerful app with so many features it’s more like a full PC software package. Its renders of the night sky are realistic and useful for showing astronomical events in advance.

- Heavens-Above: A very useful app that doesn’t simulate the stars or constellations like the others, but alerts you when the International Space Station and other satellites will be visible.

Get kids and family involved

One of the best things about stargazing is that it isn’t just a hobby for adults, children can enjoy it too.

Read our guide to getting kids involved in astronomy, or if your youngsters have already expressed and interest, it could be time to think about getting them their first telescope.

For help with this, read our guide to the best telescopes for kids.

Join an astronomy society

Have you got into stargazing but don't know how to take that next step? Or maybe you're considering buying your first telescope.

Astronomy societies are a great way to meet like-minded folk and seek advice from people who have been observing the night sky for years.

Amateur astronomy societies meet regularly and host stargazing sessions, star parties, lectures and other social events.

It may also be a good opportunity to get your first look at the night sky through a telescope, and ask advice about what sort of telescope might suit you.

They may even have a library or other resources that you could make use of as you continue your stargazing adventure.

If you're based in the UK or Ireland, read our list of UK and Ireland amateur astronomy societies and see which is closest to you.

This article originally appeared in the February 2020 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.