Mars was once just a small, red pinprick of light to the naked eye.

Then, with the advent of the telescope, it became another world we could observe and explore in the night sky.

By the 19th century, some astronomers were claiming there was evidence of a canal-building civilisation on the Red Planet.

Yet the flurry of spacecraft that began to visit Mars at the dawn of the Space Age revealed it to be a dusty, barren and inhospitable world.

More recently, scientists have discovered frozen water on Mars – even at its equator – and evidence that liquid water once flowed in ancient rivers on its surface.

And now, NASA is working with Elon Musk’s SpaceX to build a timeline for setting human feet on Mars within a generation.

It’s clear we as a species are fascinated with the Red Planet.

And as it happens, we’ve learnt quite a lot about this enigmatic, mysterious world over the past few decades…

Here are 19 facts about Mars, the Red Planet, the fourth rock from the Sun.

Mars is roughly the same age as Earth

All of the Solar System’s planets formed out of the same protoplanetary disc that surrounded the then-newborn Sun around 4.6 billion years ago.

It used to be thought that they all formed at the same time, but more recent theories suggest the gas and ice giants of the outer Solar System may have formed a little earlier than the inner, rocky planets – or a little later.

But pretty much all astronomers think Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars formed at roughly the same time.

It has an Earth-like structure

Like Earth, Mars consists of a core, surrounded by a mantle of molten rock and metal, surrounded in turn by a solid crust. There are differences, though.

Earth’s core has a solid inner zone and a molten outer zone, but Mars’s core is completely liquid

And while Earth’s crust has an average thickness of 27.3km (16.9mi), Mars’s crust ranges from 6-117km thick (4-73mi), with an average of around 45-50km (28-31mi).

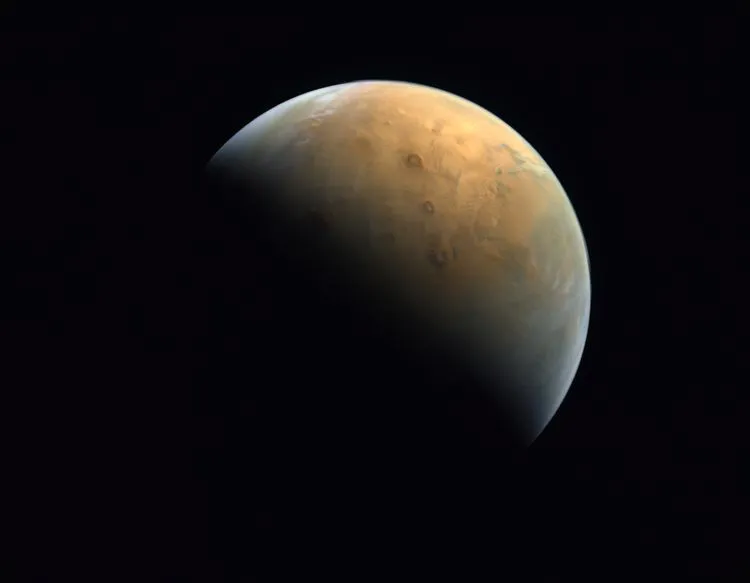

Mars is half the size of Earth

At its equator, Earth has diameter of 12,756 km (7,926 miles) and a surface area of 510 million km2 (196.9 million miles2).

Mars has an equatorial radius of 6,779 km (4,212 miles) and a surface area of 144.4 km2 (55.7 million miles2).

Crunch the numbers and that makes Mars about 53% the size of Earth.

It's a lot less dense than Earth

Although, as we’ve seen, Mars is roughly half Earth’s size, it has a mass of 6.4171 x 10^23kg, compared to Earth’s 5.9722 x 10^24 kg.

This means that Mars has an overall density of 3.9341g/cm3, compared to Earth’s 5.5136g/cm3.

This, in turn, means its surface gravity is much lower than Earth’s: 3.71m/s compared to Earth’s 9.81m/s.

Mars is the only known desert world

There are gas giants, ice giants and water worlds, but Mars is the only ‘desert planet’ that we know of.

There are probably others orbiting distant stars, but the only four rocky planets in our Solar System are Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars.

Of those, it rains water on Earth and sulphuric acid on Venus, while conditions on Mercury (where it doesn’t rain) are so extreme that analogies to Earth’s deserts don’t really stand up.

It can be seen from Earth with the naked eye

While you’ll need a telescope to really be able to tell that it’s a planet, Mars is visible with the naked eye or a pair of binoculars, in which case it looks like a very bright star.

Mars is easy to differentiate from other planets (like Venus, Mercury or Jupiter) that look like stars when seen with the naked eye, because Mars, uniquely, has a reddish hue.

It isn’t actually red

If you were standing on the surface of Mars, the ground beneath your feet would be a mixture of brown, gold and tan/beige shades.

It appears red when seen from a distance, however, because the dust in its atmosphere is rich in ferric oxides – AKA rust.

This dust also falls to the surface, of course, just like dust on Earth, so there is a layer a few millimetres deep across much of the planet’s surface.

Like snow on Earth, this dust can also accumulate in drifts that are up to 2-3m (6.5-9.8ft) deep.

The Ancient Egyptians called it Her Desher

‘Her Desher’ meant ‘the red one’, a name that was given to the planet for fairly obvious reasons.

The Sumerians, on the other hand, named the planet after their god of war, Nergal – an association that would linger on into the days of Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome.

Mars is named after the Roman god of war

The Ancient Greeks called the planet Ares after their god of war, while the Romans called it Mars after theirs.

Both names survive today: Mars in English, French and German (while the Spanish, Italians and Portuguese call it ‘Marte’) and Ares in modern Greek.

Mars is a long way from Earth

On average, Mars is about half as far away again from the Sun as Earth is, but its distance from Earth is a lot more varied.

The Solar System’s eight planets don’t orbit the Sun in neat, concentric circles on a single plane.

Instead, their orbits vary from near-circular to highly elliptical, and while their orbits are all roughly on the same plane, their orientations can vary by up to a few degrees.

Mars has a particularly eccentric orbit, so the distance from Earth to Mars at any given time can range from 54.6 million km (33.9 million miles) to 401 million km (250 million miles).

The average distance is around 225 million km (140 million miles).

A day on Mars is about the same as a day on Earth

Mars takes 24.6 hours (24 hours and 37 minutes) to completely rotate on its axis, where Earth takes 23.9 hours (23 hours and 56 minutes).

That means Martian days are pretty much the same as ours – especially when you consider that days on the other Solar System planets range from Jupiter’s 9 hours and 37 minutes, right up to Venus’s 243 Earth days.

Martian days are called ‘sols’ – which, it probably won’t surprise you to learn, is short for ‘solar days’.

A Martian year is nearly twice as long as Earth's

Mars has a much larger orbit than Earth, which also means it’s less susceptible to the Sun’s gravity and therefore orbits the Sun more slowly, with an orbital velocity of 24 km/s (53,853 mph) compared to Earth’s 29.8 km/s (66,615 mph).

As a result, Mars takes 687 days (or 669.6 sols, if you prefer) to complete one full orbit of the Sun, compared to the 365 days it takes Earth to do the same thing.

Temperatures on Mars vary enormously

Temperatures on Earth can range from –89.3°C (the lowest temperature ever recorded, in Antarctica) to 57.6°C (the highest temperature ever recorded, in the USA’s Death Valley).

Mars, on the other hand, has temperatures ranging from a terrifying –153°C to a sweltering 70°C.

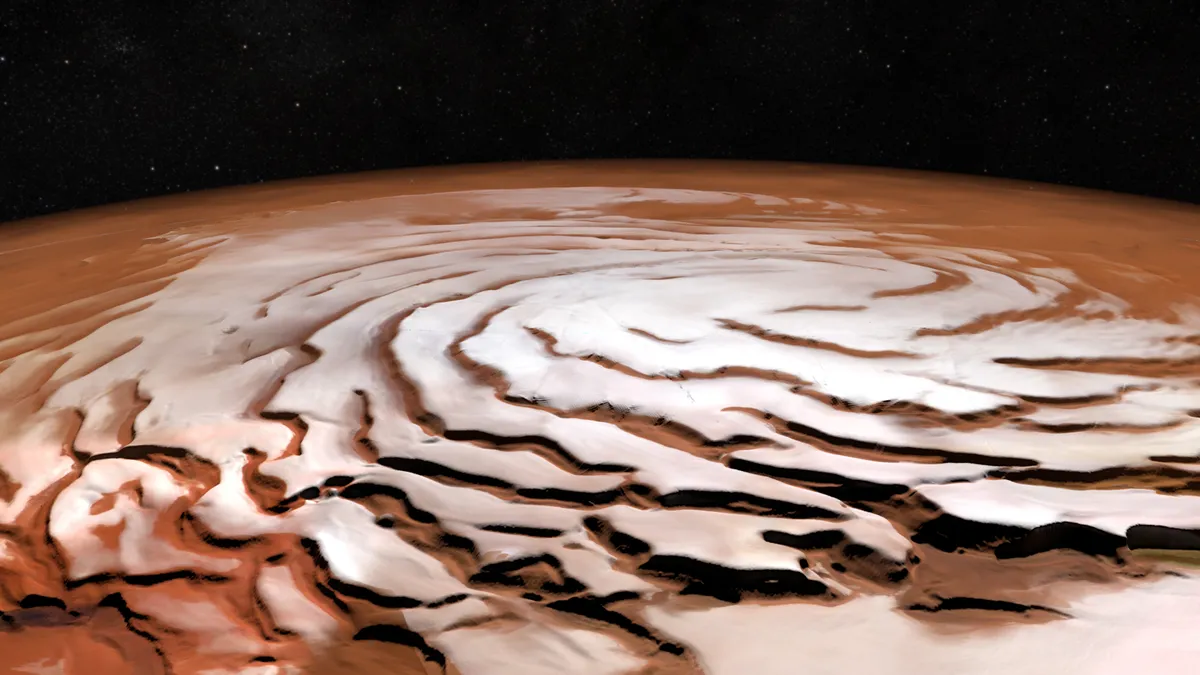

Mars is tilted

Earth’s rotational axis (ie, the axis on which it spins) is tilted at an angle of 23.5 degrees compared to its orbital axis (an imaginary line perpendicular to its orbital plane), and it’s this tilt that gives us our seasons.

Mars has a similar axial tilt of 25 degrees, so it too has seasons.

The difference is that while on Earth our seasons are of roughly equal length, those on Mars aren’t.

Due to the eccentricity of its orbit, its southern hemisphere experiences long, cold winters and hot summers, while the northern hemisphere gets short, milder winters and cooler summers.

Its atmosphere is quite different to Earth’s

Earth’s atmosphere, according to NASA, is roughly 78.08% nitrogen, 20.95% oxygen and 0.93% argon.

Everything else – including greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide and methane – makes up just 0.04% of the atmosphere overall.

Mars’s atmosphere, in contrast, is 96% carbon dioxide, 1.93 % argon and 1.89% argon, with the rest mostly oxygen and water vapour.

Mars's atmosphere is very thin

Because Mars has no magnetosphere, gases close to its surface are more susceptible to being blown away by the solar wind.

Indeed, ionised atmospheric particles have been detected trailing off into space behind Mars by two NASA orbiters, the Mars Global Surveyor (1996-2007) and Mars Express (2001-ongoing).

As a result, it has a far lower atmospheric density and far less atmospheric pressure than Earth, because there are so many fewer gas molecules per cubic metre.

Mars’s thin atmosphere does strange things

In the thin ‘air’ of Mars, there are fewer gaseous molecules available to store heat, so heat energy that arrives from the Sun and warms the planet is very quickly radiated outwards.

NASA has calculated that if you stood on the Martian equator at noon, the temperature at your feet would be a balmy 24°C (75°F) – but your head would be experiencing winter-like conditions of 0°C (32°F).

We’re calling this one now: if humans ever do colonise Mars, bobble hats are going to be that year’s must-have fashion accessory!

Mars has no magnetosphere

The exchange of heat between Earth’s solid inner and liquid outer cores creates a magnetic field, which in turn leads to the formation of a magnetosphere – a region of space immediately surrounding our planet in which any charged particles are affected by said magnetic field.

Mercury, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune also have magnetospheres, but Mars, Venus and Pluto don’t.

In Mars’s case, it probably did have a magnetosphere once – the planet does still have a magnetic field, albeit a weak one – but for some reason this was stripped away, perhaps as a result of asteroid bombardment.

This is why the Martian atmosphere is so thin: with no magnetoshere to protect them, gases around the planet are quickly stripped away by the solar wind.

Mars has aurora

On Earth, you generally need to be somewhere up towards the North Pole, or down towards the South Pole, if you want to see the aurora borealis or aurora australis (respectively).

That’s because when charged particles from the Sun hit Earth’s atmosphere, they’re steered towards the poles by its magnetosphere.

Mars has no magnetosphere – so stunning aurorae can be seen from pretty much anywhere on the planet.

The Perseverance rover even detected green aurora on Mars, from the surface.

Mars has a north-south divide

Mars is a planet of two halves. Its northern hemisphere is largely low-lying and flat, having been ‘smoothed out’ by lava flows (and possibly a former ocean) over billions of years.

Its southern hemisphere, in complete contrast, is mostly highlands that are covered with thousands of impact craters.

This is known as the Martian dichotomy.

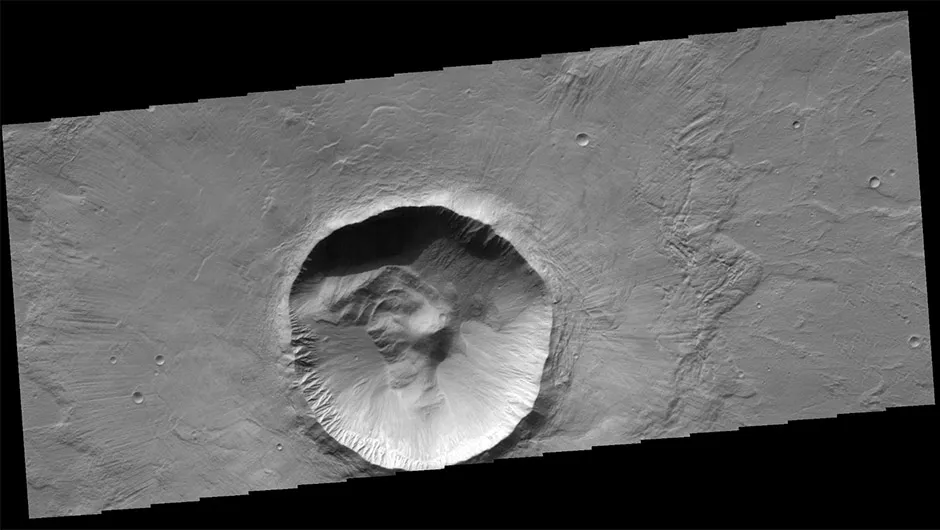

It’s home to the Solar System’s biggest impact crater

There are over 43,000 known impact craters on Mars that have a diameter of 5km (3.1mi) or more, and hundreds of thousands over 1km (0.62mi).

But the biggest of them all is Utopia Planitia, with a diameter of around 3,300km (2,100mi).

However, geological and meteorological processes have eroded much of Utopia’s visible topography over billions of years, so Mars’s largest crater that actually looks like a crater is Hellas Planitia, with an approximate diameter of 2,300km (1,400mi).

The latter can even be seen from Earth, but you’ll need decent telescope.

Mars also has the biggest volcano

Situated in the upland region of Tharsis, Olympus Mons is a shield volcano that measures over 600km (370mi) across.

It’s the biggest volcano in the Solar System.

Because Olympus Mons is so large, it’s hard to state a definitive height for it, but its highest peaks stand 21km (13mi) above the local terrain and some 26km (16mi) higher than the plains of Amazonis Planitia, 1,000km away to the northwest.

That’d make it twice as tall as Mauna Kea (Earth’s tallest volcano) measured from seabed to summit, and three times as tall as Mount Everest, which rises just 8.8km (5.5mi) above sea level.

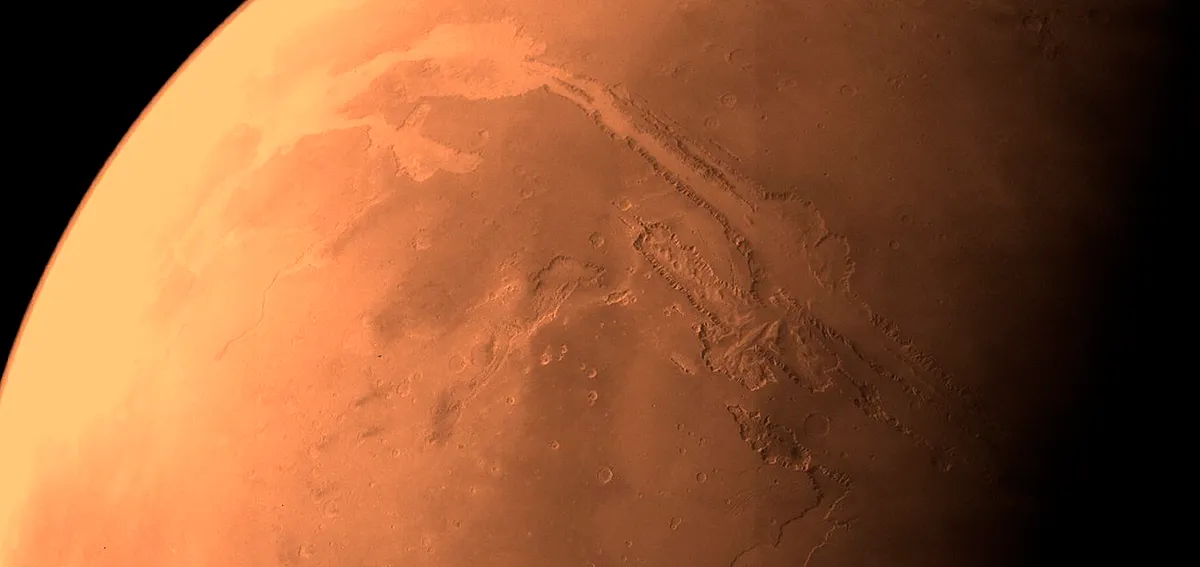

Mars has the largest canyon

Ever visited the Grand Canyon? It’s undeniably impressive, but it pales in comparison to the Valles Marineris on Mars.

The Grand Canyon is 446km (277mi) long and up to 2km (1.2mi) deep. Valles Marineris stretches out over 4,000km (2,500mi) and, in some areas, is up to 7km (4.3mi) deep.

Liquid water was once abundant on Mars

Ever since the Viking probes sent back images of what looked distinctly like ancient coastlines in 1976, astronomers have explored the idea that water was once abundant on Mars.

Many now believe that during its ancient history, Mars was home to at least one large ocean, possibly covering as much as one-third of the planet.

But that idea wasn’t finally confirmed until 2004, when the NASA rover Opportunity confirmed the presence on Mars of jarosite, a mineral that can ONLY form in the presence of liquid water.

Liquid water could explain many of its surface features

Many features of Mars’s topography and geology make a lot more sense if we know there was water there in the past.

The former presence of a large ocean may help to explain the low-lying, smooth surface of Mars’s northern hemisphere, while over 40,000 surface features have been identified as former riverbeds, lake beds and river deltas.

Mars was first mapped in 1840

Begun in 1830 and finished in 1840, the first comprehensive map of Mars was produced by Johann Heinrich von Mädler and Wilhelm Beer, two German astronomers who are much better known for producing the first proper map of the Moon in 1834-37.

The pair also calculated the planet’s rotation period, which we know today to be 24 hours and 37 minutes – their estimate was out by just 1.1 seconds.

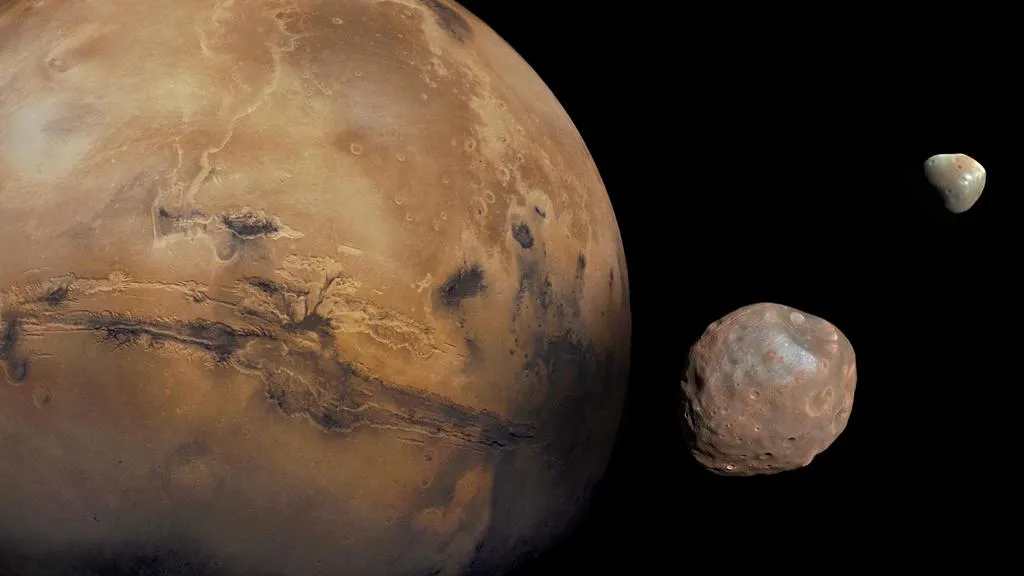

Mars has two moons

Mars has two natural satellites, named Phobos and Deimos.

Both are very small compared to Earth’s Moon, measuring just 22km (14mi) and 12km (7.5mi) in diameter respectively, and they weren’t discovered until 1877, when US astronomer Asaph Hall spotted them through a telescope, naming them after Ares’s twin sons, who in Greek mythology drove his chariot.

Most astronomers believe the two moons to be captured asteroids, though there are also competing ‘accretion’ and ‘giant impact’ hypotheses.

Phobos won’t be around forever

Phobos’s days are numbered. It orbits Mars at a distance of just 6,000 km (3,700 mi).

That’s the tightest orbit of any natural satellite in the Solar System, and places Phobos well within the Roche limit – an imaginary line in space surrounding a planet, outside which the gravity of any orbiting bodies exceeds the tidal forces imposed on that body by the planet itself.

As a result, Phobos gets roughly 2cm (0.79in) closer to Mars with every passing year, and will eventually either crash into the planet or be ripped apart by tidal forces – though that won’t happen for another 30-50 million years.

NASA/JPL-Caltech/GSFC/Univ. of Arizona

Mars has no rings, but might do in future

Mars has no visible ring surrounding it, though some astronomers have suggested there may be a faint, diffuse ring of dust somewhere between the orbital distances of Phobos and Deimos (6,000km and 23,460 km, or 3,700mi and 14,580 mi, respectively).

But there is some evidence that it may have had a ring around 3.5 to 4 billion years ago.

And Mars might gain a ring in future. Check back in another 30-50 million years.

If Phobos succumbs to tidal forces and is ripped apart, the debris it leaves behind is likely to leave the Red Planet with a natty-looking ring, just like those around Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune.

Sound travels more slowly on Mars

Due to a combination of low atmospheric pressure and much higher levels of C02, sound travels more slowly through the ‘air’ on Mars than it does on Earth.

The speed of sound in air, on Earth, is usually quoted at 343 metres per second, though this does vary with both temperature and altitude.

On Mars, sound travels at around 240-250 metres per second, depending on the exact frequencies involved.

Mars's surface is roughly equal to all of Earth's land

Mars is a lot smaller than Earth, but it’s also (mostly) devoid of water.

As a result, the planet’s overall surface area is only a tiny bit less than the surface area of all the dry land here on Earth.

This doesn’t actually signify or reflect anything, or tell us very much, but it’s a neat little fact all the same.

People thought Martians were building canals

Serious astronomers once thought Mars was populated by canal-building Martians!

This idea came from Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli, who in 1877 was attempting to map the Martian surface in greater detail.

He thought he spotted long, straight lines – since shown to have been an optical illusion – crossing the surface, and called them “canali”.

The Italian word just means ‘channels’ or ‘grooves’ but was mistranslated to ‘canals’ in English, and the idea caught on – so much so that US astronomer Percival Lowell (who founded the Lowell Observatory) published three books on the subject between 1895 and 1908.

The canals theory wasn't disproven til the 1960s

Once Mariner 4 started sending back images of Mars in 1965, it soon became apparent that what Schiaparelli had mistaken for straight lines were mostly irregular, wobbly chains of impact craters, and that there were no canals.

Or canal-building little green men, for that matter. D’oh!

Martian ‘soil’ is toxic to humans

While the Martian regolith is mostly made of basalt and silica – and does contain compounds necessary for the growth of plants, such as magnesium, sodium potassium and chlorine – it also consists of 0.6% perchlorate by weight.

Perchlorates are salts of perchloric acid that are used, among other things, in rocket fuel and fireworks, and as an electrolyte in lithium batteries.

Exposure to them at even such a seemingly low concentration would be hazardous to your health.

It's probably the most explored body after Earth

So far, humankind has managed to land robotic rovers (as opposed to static probes) on three extraterrestrial bodies: the Moon, Mars and the asteroid Ryugu, which a JAXA rover briefly visited in 2018.

The Moon was the first to receive a rover, has been visited by the most rovers (eight), and of course is the only body apart from Earth that humans have ever walked upon – but rovers have spent far more time exploring Mars, with most lunar rovers having lifespans measured in weeks or months rather than years.

NASA has successfully landed five rovers on the planet, including the now-defunct Sojourner (1997), Spirit (2004-2010) and Opportunity (2004-2018) as well as Curiosity (2011-present) and Perseverance (2021-present).

The Chinese space agency CNSA also successfully landed a rover called Zhurong there in 2021, as part of its Tianwen-1 mission, but had to deactivate it just a year later when its solar panels became covered in dust following a Martian sandstorm.

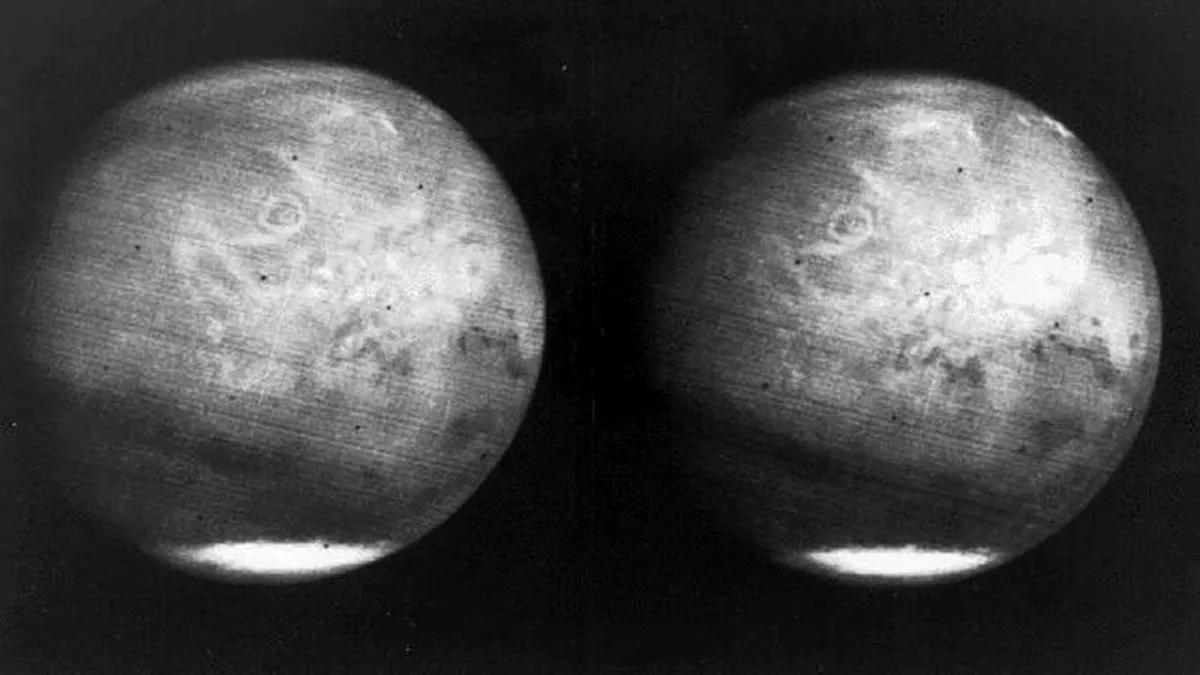

The first Mars flyby took place in 1965

The first human-made spacecraft to reach Mars was NASA’s Mariner 4, which launched on 28 November 1964 and carried out a flyby on 14-15 July 1965.

This was only the second-ever successful flyby of another planet – and the first to send back pictures, because Mariner 2, which had completed a flyby of Venus three years earlier, hadn’t been equipped with a camera.

To give you some idea of the technological challenges involved, Mariner 4 data was sent back to Earth and then rendered by NASA computers at such a slow rate that the ground-based control team were able to complete their own colour-by-numbers version of the first picture – based on the data they were receiving and created using pastel crayons from a local art store – before a printout became available!

Mariner 9 was the first spacecraft to orbit Mars

Launched from Cape Canaveral on 30 May 1971, Mariner 9 went into Martian orbit on 14 November, narrowly beating Soviet probes Mars 2 and Mars 3, which arrived at the Red Planet a week later.

Mariner 9 remained in orbit until October 1972, during which time it sent back 7,329 images of Mars, spanning 85% of the planet’s surface.

Viking 1 was the first spacecraft to land on Mars

The Viking 1 mission, which included both an orbiter and a lander, launched from Cape Canaveral on 20 August 1975 and entered Mars orbit on 19 July 1976, with its lander section touching down on the Red Planet on 20 July.

It had sent back its first image within five minutes of landing, and remained operational for 2,306 days, taking pictures and analysing samples of the Martin regolith for signs of life.

Mars has mysterious caves

Images captured by NASA’s 2001 Mars Odyssey orbiter have revealed the presence of what appear to be a serious of cave entrances on the flanks of the Arsia Mons volcano.

These entrances, dubbed the seven sisters, measure up to 250m (820ft) across, while the caves themselves are believed to be at least 70m (230ft) deep.

If humans do ever reach Mars, these caves could potentially offer shelter from UV radiation and solar flares.

What are your favourite facts about Mars? Let us know by emailing contactus@skyatnightmagazine.com

![Frosty white water ice clouds and swirling orange dust storms above a vivid rusty landscape reveal Mars as a dynamic planet in this sharpest view ever obtained by an Earth-based telescope. The Earth-orbiting Hubble telescope snapped this picture on June 26, when Mars was approximately 43 million miles (68 million km) from Earth - its closest approach to our planet since 1988. Hubble can see details as small as 10 miles (16 km) across. Especially striking is the large amount of seasonal dust storm activity seen in this image. One large storm system is churning high above the northern polar cap [top of image], and a smaller dust storm cloud can be seen nearby. Another large duststorm is spilling out of the giant Hellas impact basin in the Southern Hemisphere [lower right]. Acknowledgements: J. Bell (Cornell U.), P. James (U. Toledo), M. Wolff (Space Science Institute), A. Lubenow (STScI), J. Neubert (MIT/Cornell) Frosty white water ice clouds and swirling orange dust storms above a vivid rusty landscape reveal Mars as a dynamic planet in this sharpest view ever obtained by an Earth-based telescope. The Earth-orbiting Hubble telescope snapped this picture on June 26, when Mars was approximately 43 million miles (68 million km) from Earth - its closest approach to our planet since 1988. Hubble can see details as small as 10 miles (16 km) across. Especially striking is the large amount of seasonal dust storm activity seen in this image. One large storm system is churning high above the northern polar cap [top of image], and a smaller dust storm cloud can be seen nearby. Another large duststorm is spilling out of the giant Hellas impact basin in the Southern Hemisphere [lower right]. Acknowledgements: J. Bell (Cornell U.), P. James (U. Toledo), M. Wolff (Space Science Institute), A. Lubenow (STScI), J. Neubert (MIT/Cornell)](https://c02.purpledshub.com/uploads/sites/48/2021/05/Mars-d1e4afb.jpg?w=300&webp=1)