The question of how black holes grow should be an easy one to answer: they absorb material from their surroundings.

But despite their fearsome reputation, supermassive black holes don’t rampage through their host galaxies; instead, they can be found sitting quietly in the middle.

More on black holes

And while it’s true that material that comes too close to them will inevitably fall in, most of the stuff in a galaxy is far enough away to be safe.

As long as we don’t get too near, we have nothing to fear from the black hole at the centre of the Milky Way.

So to feed a black hole, we need to create what’s known as an AGN, or active galactic nucleus, with a dense accretion disc of material around the black hole, and for that we need to drive material into the centre of the Galaxy.

It’s long been suspected that an effective way to do that is via a merger between two galaxies, or at least a close encounter.

The gravitational pull of a passing or colliding neighbour galaxy can drag stars and gas out of stable orbits and thus down towards the black hole.

Does this actually happen? And if it does, can such a process fuel the brightest, most active AGNs, those detected by radio emission from the accretion disc or from powerful jets driven away from the galactic centre, powered by the twisted magnetic fields that are produced?

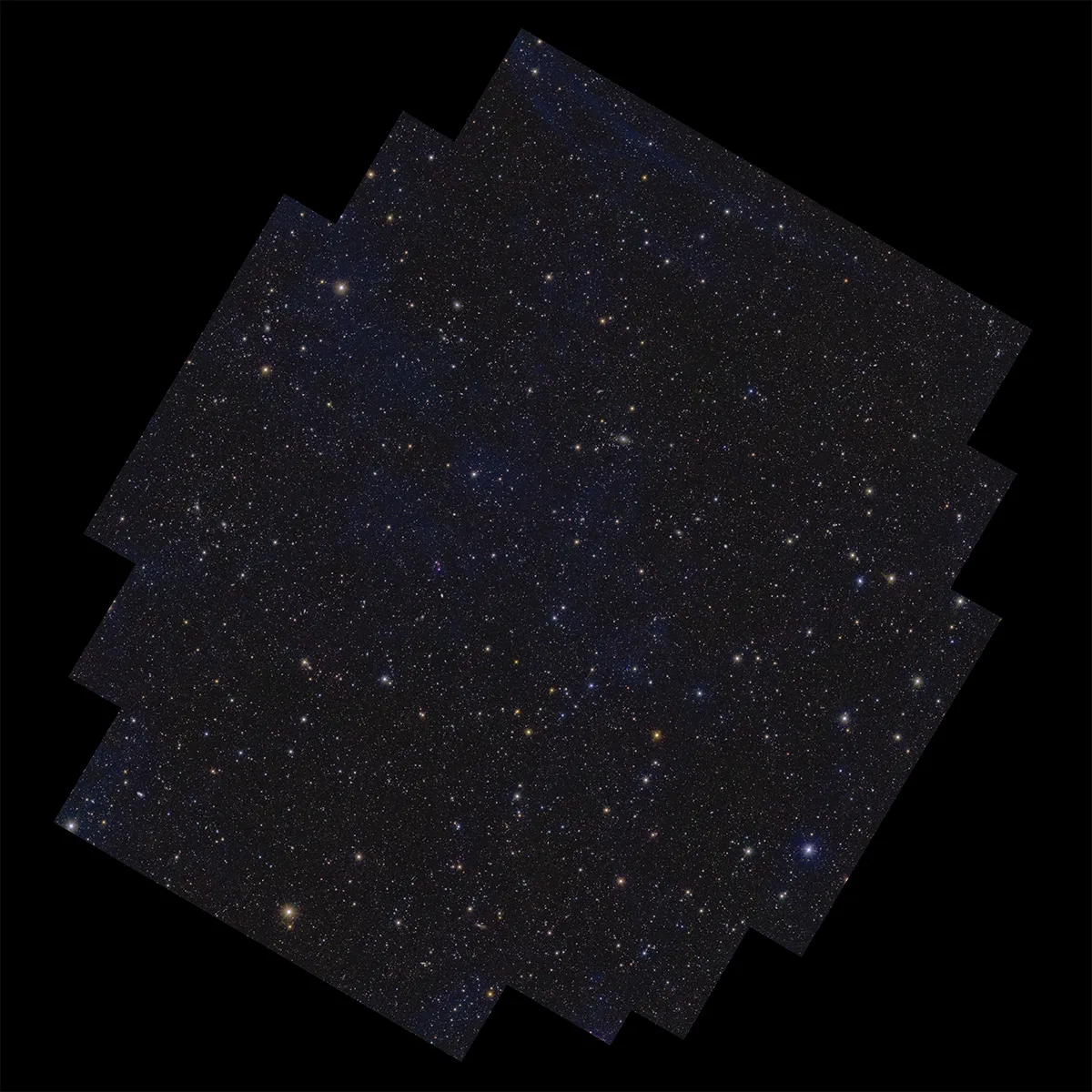

Armed with new, deep images from ESA’s Euclid space telescope, that’s what the authors of one science paper set out to discover.

Studying hungry black holes

Led by Manuela Magliocchetti at INAF in Italy, the team focus on the Euclid Deep Field North, a region the mission has already stared at for some time.

Within this patch of sky, they use data from the LOFAR interferometer to identify galaxies which are bright in radio emission, dividing them carefully between those which are true AGNs and those where the radio emission seems to come from intense star formation.

Meanwhile, Euclid images of these galaxies were analysed to see which showed signs of the distortion or disruption one would expect during a merger or other encounter.

This all amounts to a lot of careful work. But the net result is clear: bright radio AGNs, whose black holes are growing rapidly, are much more likely to be found in merging galaxies than not.

In fact, about 40% of them are in mergers, and the opposite is true for those galaxies whose radio emission seems to be associated with star formation.

This effect seems stronger in the local Universe than earlier on.

The authors speculate that while galaxies had plenty of gas billions of years ago, in the present-day Universe fuel is scarcer, and so the effect of mergers is more important.

The merger effect becomes stronger still if we only consider those galaxies that have the most dramatic activity.

Presumably, these represent systems where mergers have been really efficient at supplying gas, helping their black holes to grow.

With this work being based on only the initial test release of Euclid data, I’m looking forward to more from ESA’s newest observatory.

Its wide survey, as well as deep images like those used here, should help us disentangle the many processes that are shaping the galaxies around us today, and the black holes within them.

Chris Lintott was reading Euclid: Quick Data Release (Q1) – The Connection between Galaxy Close Encounters and Radio Activity by M Magliocchetti et al. Read it online at: arxiv.org/abs/2511.02970.

This article appeared in the January 2026 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine