The objects appear to be neither planet nor star, but somewhere between the two

Hundreds of strange planet-like objects have been found hidden in the Orion Nebula, and could be a new class of cosmic bodies that defies our current understanding of how planets form.

Discovered by the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), the free-floating entities are neither star nor planet, and have been dubbed Jupiter-mass binary objects, or JUMBOs for short.

What are JUMBOs?

The objects are large gassy objects with masses around the same as Jupiter in our own Solar System and traces of steam and methane have been found in their atmosphere.

Of the many JUMBOs in Orion already discovered, most are in pairs, hence the binary part of their name.

They are relatively young in cosmic terms – a mere one million years old – with surface temperatures of around 1,000 ºC.

While hot for a planet, this is very cool for a star and with no star to warm them, they will rapidly cool even further over time.

What is the Orion Nebula?

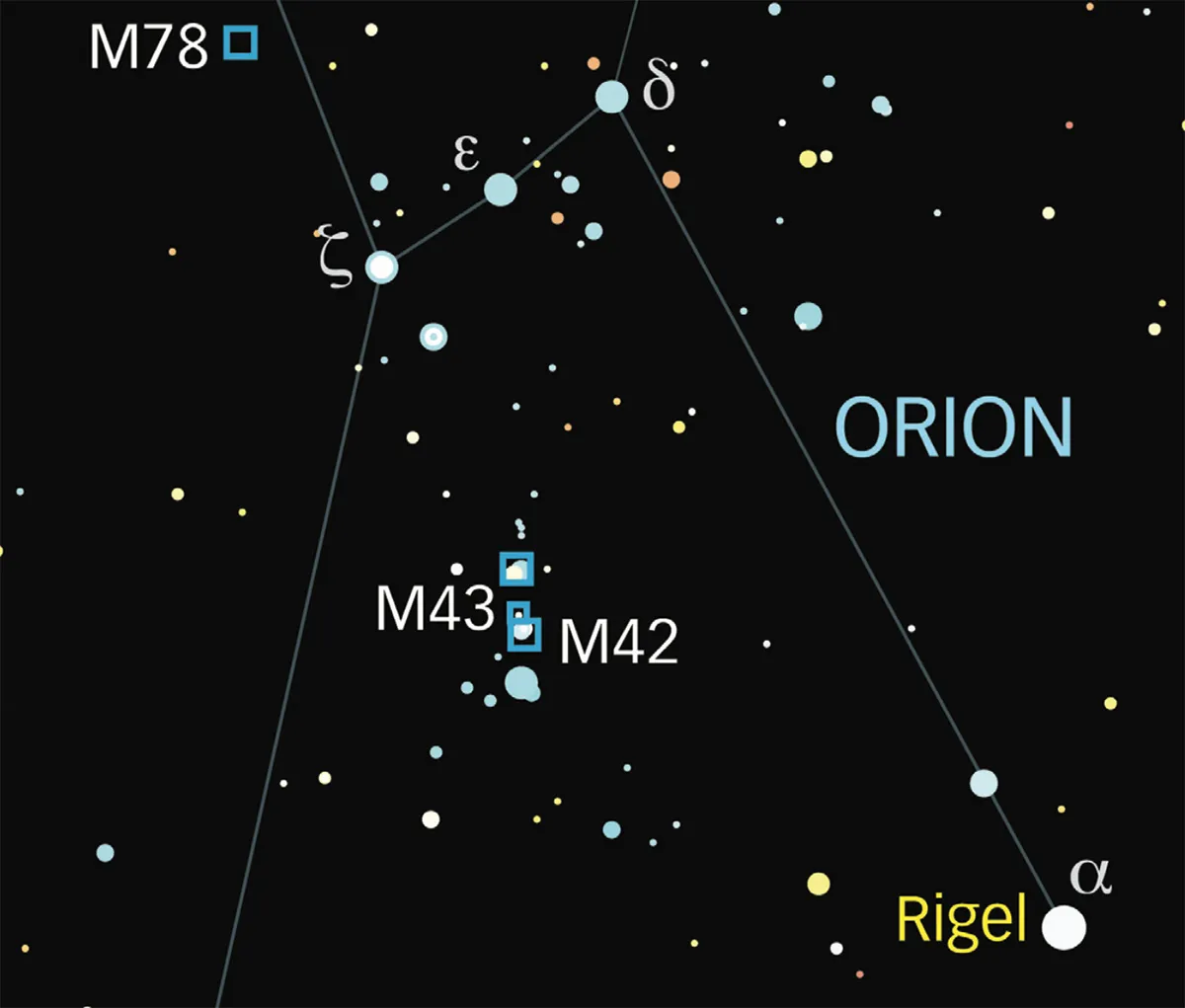

The Orion Nebula, also known as Messier 42, is located 1,344 lightyears away in the constellation of Orion, the Hunter.

It appears as a faint fuzzy patch near the tip of Orion’s Sword, which hangs from Orion’s Belt and is visible to the naked eye.

The region is filled with gas and dust, which blocks visible light.

Infrared light, however, can cut through the dust, which makes JWST the perfect tool for revealing the Orion Nebula’s inner workings.

This has been a revelation of astronomers, as the Orion Nebula is also a stellar nursery, meaning JWST allows them to lift the veil and see how stars form for the first time.

The JWST has conducted a full survey of the Orion Nebula's inner region.

These images reveals the intricate structure of gas and dust formed as the gas clumps together to form new stars, only for their stellar winds to carve out bubbles in the clouds that created them.

How to stars form in Orion?

Stars form when a cloud of hydrogen gas begins to clump together, eventually collapsing under the weight of its own gravity.

When the core becomes dense enough, the hydrogen begins to undergo fusion, allowing the star to shine.

Stars can form in a range of sizes, but the smallest have masses around 80 times that of Jupiter. Below this the core isn’t dense enough to ignite.

Smaller objects can coalesce through the same method but will form brown dwarfs, sometimes called failed stars.

There is a lower limit to this star-like gravitational collapse, however, of around three to seven times Jupiter’s mass.

The JUMBOs in Orion are all below this limit, meaning they couldn’t have formed this way according to our current understanding.

Could the JUMBOs in Orion be free-floating planets?

Another possibility is that the JUMBOs formed more like planets, as free-floating planets have been found throughout the Galaxy.

One explanation for these rogue planets is that they formed in planetary systems, but in the gravitational shuffle of the growing planets they were ejected.

If this was the case, though, then the mystery becomes why are so many JUMBOs in Orion in binary pairings – if they were ejected from a chaotic system, how did they stay together?

Astronomers will now look to study these new objects in great detail to better understand what they are, and what they might mean for our understanding of planetary evolution.