Astronomers have discovered a group of planets orbiting a distant star that appears to be the opposite of what they would expect to find.

In our own Solar System, rocky planets like Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars are close to the Sun, whereas gassier outer planets Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune, are further out.

One theory as to why this happens is that, when planets are forming around young stars, fierce radiation from the star sweeps away their gassy atmospheres, leaving solid cores behind.

This leads to groups of small, rocky planets orbiting close to the star.

Further away, it's much cooler, so gas giants have a greater chance of forming and holding onto their gaseous bodies.

Astronomers say this pattern is repeated in planetary systems across our Galaxy, but they've found one that does things a little differently.

More strange planets

A mirror to our own Solar System

Since the first exoplanets were discovered in the mid-1990s, astronomers have found over 6,000 confirmed words orbiting distant stars, with many more candidates awaiting confirmation.

The more we learn about distant planets orbiting distant stars, the more we learn about our own Solar System. Specifically, astronomers are learning how unlike other planetary systems it is.

One example is a type of planet called 'super Earths' or 'mini Neptunes', which are common across the Galaxy, yet none are to be found orbiting our Sun.

And now a team of astronomers have found a system of planets orbiting a distant star that seems to upend the rocky planet / gas planet convention.

Finding the inside-out system

The team behind the discovery was led by Assistant Professor Tom Wilson at the University of Warwick in the UK.

They looked at a cool, faint red dwarf star known as LHS 1903 and the planets in orbit around it.

There was one rocky planet orbiting close to the star and two gas giants further out. So far, so normal.

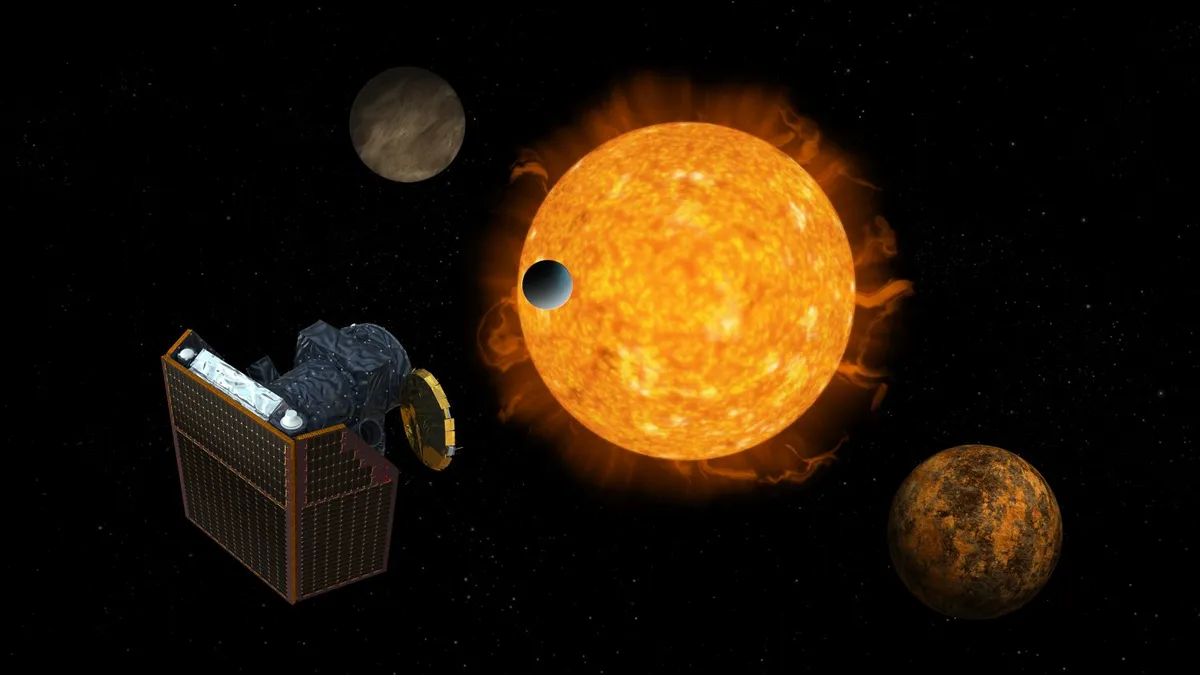

But the European Space Agency's CHaracterising ExOPlanet Satellite (CHEOPS) revealed an extra fourth planet on the outer edge.

This fourth, most distant world fis rocky, creating what the team are describing as a "rare inside-out" system.

The distant rocky planet seems to have either lost its gassy atmosphere, or never had one in the first place.

How could this be? The team found evidence that suggests the four planets around star LHS 1903 didn't form at the same time.

Instead, they formed one after another in a process called, appropriately, 'inside-out planet formation'.

Explaining the inside-out formation

Planets form out of the rotating disks of gas and dust that are left surrounding newborn stars.

These disks are essentially the leftover ingredients out of which the star formed, and within these discs, planets may eventually grow, as clumps of material are pulled together by gravity.

Current theories predict planets form at roughly the same time around a star. But perhaps, in the case of LHS 1903, each planet was formed one after the other.

That would mean the planets all formed in their own time, sweeping up nearby dust and gas, each world forming one after the other.

The most distant rocky planet may have formed much later than the inner planets, in a region far from the star where the gas had run out.

The discovery is challenging what we know about how planets form around stars.

"The differences between sibling planets in this closely packed family of four offer important new clues to their birth environment around a small star much older than the Sun," says study co-author Professor Andrew Cameron from the University of St Andrews in the UK.

The University of St Andrews' School of Physics and Astronomy analysed much of the data that led to the discovery of two additional planets in the system.

"By the time this final outer planet formed, the system may have already run out of gas, which is considered vital for planet formation," says Dr. Thomas Wilson.

"Yet here is a small, rocky world, defying expectations. It seems that we have found first evidence for a planet that formed in a gas-depleted environment."

Isabel Rebollido, a Research Fellow at the European Space Agency, says: "Historically, our planet formation theories are based on what we see and know about our Solar System.

"As we are seeing more and more different exoplanet systems, we are starting to revisit these theories."