It’s shaped like a lemon, has a chemical composition unlike any we’ve ever seen before and may be raining diamonds internally.

Of the more than 6,000 confirmed exoplanets so far discovered, PSR J2322-2650b is one of the weirdest that scientists have come across to date.

More cosmic weirdness

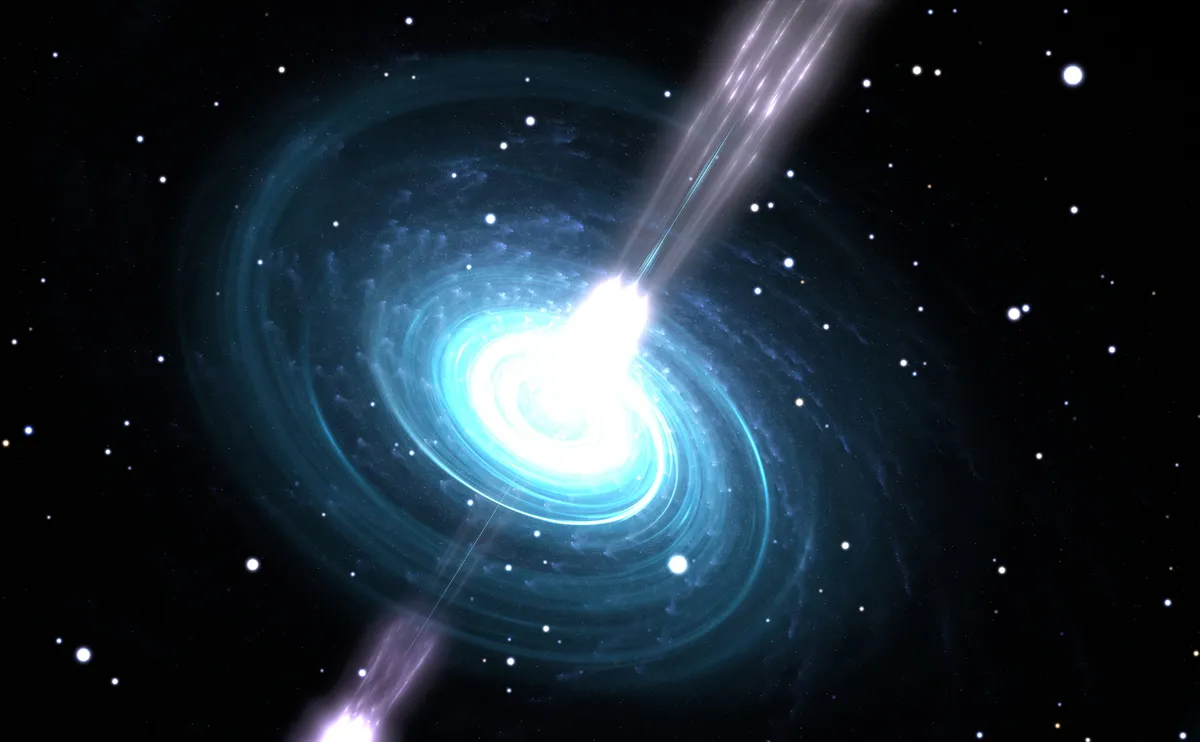

PSR J2322-2650b orbits a millisecond pulsar – a type of fast-spinning neutron star.

While pulsars generally aren’t uncommon in the Universe, millisecond pulsars are comparatively rare.

They derive their name from the fact that they emit beams of electromagnetic radiation at intervals measured in just a few milliseconds, whereas for an 'ordinary' pulsar the interval between pulses is usually a few seconds.

A pulsar perfect for Webb

The fact that PSR J2322-2650b orbits a pulsar is very relevant to the new discovery, because pulsars mostly only emit gamma rays and other high-energy particles.

And these are invisible to the infrared-waveband equipment mounted on the James Webb Space Telescope.

That means JWST can study the planet without bright light from its parent star getting in the way – something that’s impossible with exoplanets in tight orbits around main sequence stars such as our own Sun.

"This system is unique because we are able to view the planet illuminated by its host star, but not see the host star at all," says Stanford University doctoral candidate Maya Beleznay, who was involved in the research.

"So we get a really pristine spectrum. And we can study this system in more detail than normal exoplanets."

Accordingly, the recently discovered PSR J2322-2650b becomes one of just 150 exoplanets whose atmospheres have so far been studied in detail. And when JWST scientists began to do just that, they were in for a shock.

"I remember after we got the data down, our collective reaction was 'What the heck is this?'" says study co-author Peter Gao, from the Carnegie Earth and Planets Laboratory in Washington.

"It's extremely different from what we expected."

Carbon galore, but where’s all the oxygen?

At first glance, PSR J2322-2650b appears quite similar to many other exoplanets.

Its mass, radius and temperature are in-line with what we expect to see from so-called ‘hot Jupiters’ – and hot Jupiters are the most common category of exoplanet.

Admittedly, the idea of a hot Jupiter orbiting a pulsar is in itself worth of note.

Only a handful of pulsars are known to play host to exoplanets, and none of those are gas giants.

What’s also unusual is the planet’s shape. Because it orbits its pulsar companion at a distance of just 1.6 million km (1 million miles) or so, it is very susceptible to its gravitational influence, resulting in its strange lemon-like shape.

But it was when scientists began carrying out a spectral analysis of the light coming from PSR J2322-2650b that they got their biggest surprise.

An impossible atmosphere

That analysis revealed that PSR J2322-2650b’s atmosphere is composed mostly of helium and carbon – the latter in its molecular forms C3 and C2.

And that shouldn’t be possible, because at the kinds of temperatures found on PSR J2322-2650b (650-2,400°C, or 1,200-3,700°F if you prefer) molecular carbon shouldn’t exist.

Carbon bonds quite easily with other molecules, so if there’s any nitrogen or oxygen around, it will form compounds with those gases.

And there usually is some nitrogen or oxygen around. In fact, of those 150 well-studied exoplanets mentioned previously, only PSR J2322-2650b has any molecular carbon in its atmosphere at all.

PSR J2322-2650b, on the other hand, has so much carbon in its atmosphere that scientists now believe the high pressures found inside the planet are likely to compress that carbon into diamonds.

If that’s correct, then such diamonds are likely to be falling towards the planet’s core like rain.

"Instead of finding the normal molecules we expect to see on an exoplanet — like water, methane and carbon dioxide — we saw molecular carbon, specifically C3 and C2," says principal investigator Michael Zhang, from the University of Chicago.

"This is a new type of planet atmosphere that nobody has ever seen before."

It’s a mystery

So what’s going on? The short answer is: we don’t know.

In some ways, the relationship between PSR J2322-2650b and its parent star is similar to that seen in a so-called ‘black widow’ system.

A black widow is a type of binary star in which a low-mass, Sun-like star and a pulsar orbit each other.

In such cases, the pulsar’s radioactive ‘wind’ slowly erodes the companion star away. The problem is, PSR J2322-2650b is an exoplanet, not a star.

So it’s unlikely to be a true black widow. At the same time, none of our current models of planetary formation can explain how PSR J2322-2650b came into being either.

"Did this thing form like a normal planet? No, because the composition is entirely different," says Zhang.

"Did it form by stripping the outside of a star, like ‘normal’ black widow systems are formed? Probably not, because nuclear physics does not make pure carbon.

"It's very hard to imagine how you get this extremely carbon-enriched composition. It seems to rule out every known formation mechanism."

Until we can get to the bottom of this riddle, PSR J2322-2650b is likely to have planetary scientists scratching their heads for a while yet.

But as study co-author Roger Romani, also of Stanford University, puts it: "It's nice to not know everything. I'm looking forward to learning more about the weirdness of this atmosphere. It's great to have a puzzle to go after."

The team detailed their findings in a paper published 16 December in the scientific journal The Astrophysical Journal Letters.