An armada of 3 missions from 3 countries are launching to explore Mars in 2020. The simultaneous timing is no coincidence: every 26 months, Earth and Mars are in the right relative positions to enable a fuel-efficient transfer. But what are these new Mars missions, and what might they discover?

On Thursday 18 February 2021, with protection from a heat shield and 20m-wide parachutes, NASA's Perseverance rover is scheduled to descend through the thin Martian atmosphere.

Minutes later, the six-wheeled machine will be lowered to the Red Planet’s surface from a sky crane that is hovering at low altitude.

Read more about Mars exploration:

- Interview with a NASA Opportunity scientist

- Ancient lakes confirmed on Mars

- Ancient oasis points to Mars's wet past

Around the same time the UAE’s Hope spacecraft will enter the orbit of Mars to study the planet’s atmosphere and climate.

Months later the lander part of the Chinese Tianwen-1 mission will touch down elsewhere on Mars, releasing its own miniature rover to explore the desert world.

If it weren’t for technical problems and logistical hiccups as a result of COVID-19, Europe and Russia’s Rosalind Franklin mission would be joining them. Instead, ESA is now targeting the September 2022 launch window.

At the time of writing, Perseverance, Tianwen-1 and Hope are still on schedule, despite COVID-19-related travel restrictions and the need for additional quarantine measures.

At NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, for instance, technicians have been working around the clock for the past couple of months to get everything ready on time.

The UAE's Hope mission to Mars

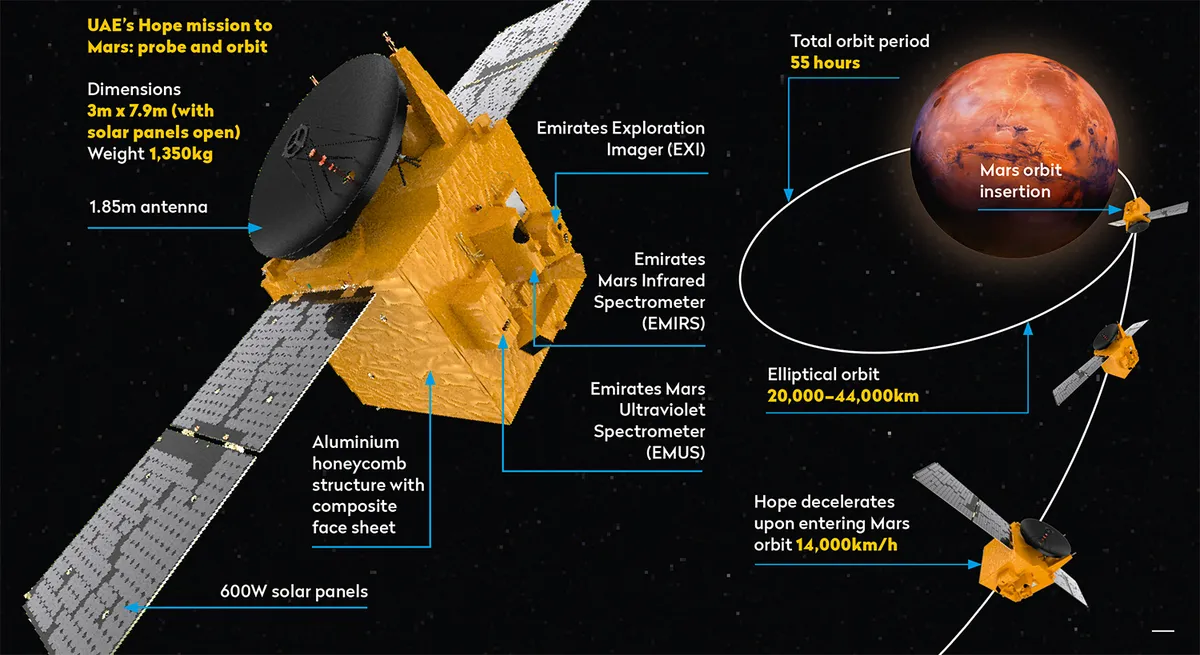

Hope (or ‘Al-Amal’ in Arabic) is a 1,350kg spacecraft, the size of a small garden shed, built by the Mohammed bin Rashid Space Centre (MBRSC), with important contributions from three American universities. Assembly of the craft took place at the University of Colorado in Boulder.

Flying past another planet is relatively easy – 55 years ago, Mariner 4 passed by Mars, becoming the first spacecraft to achieve that goal. Entering orbit is harder, with Mariner 9 being the first to succeed, in 1971.

The real challenge is a soft landing on the surface, as numerous crashes and failures in the past testify to.

So it shouldn’t come as a surprise that the United Arab Emirates (UAE) Space Agency isn’t aiming for a landing on its first interplanetary space mission, which will

arrive at Mars in 2021, the year that the UAE celebrates the 50th anniversary of its foundation.

Of the three new Mars missions, it's the first to have left Earth. Emirates launched the Hope probe on 19 July 2020 from the Japanese island of Tanegashima.

From its wide, 55-hour elliptical orbit, with the lowest point still at 20,000km from the planet’s surface, Hope will operate as a Martian global weather satellite, using a camera as well as infrared and ultraviolet spectrometers to study wind patterns, dust storms, daily and seasonal weather changes and atmospheric processes that may shed light on long-term climate evolution.

China's mission to Mars

China’s Tianwen-1 mission (the name translates as ‘heavenly questions’) is much more ambitious, although the China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation (CASC) hasn’t revealed many details about the project.

“We do not know much about the Chinese mission,” says Jorge Vago, the European project scientist for the Rosalind Franklin mission, “although we have some collaboration, providing them with data from our Mars Express orbiter on their selected landing location.”

In September 2019, China chose two potential landing sites in Utopia Planitia, the huge rolling northern hemisphere plain where NASA’s Viking 2 lander touched down back in 1976.

Tianwen-1 is a three-part space mission, consisting of an orbiter, a lander and a small rover.

After launch on a Long March 5 rocket, the five-tonne spacecraft will enter Mars orbit in February next year, but the lander probably won’t descend until April or May 2021.

Both the lander and the 240kg rover are based on the design of China’s successful Chang’e lunar missions.

The orbiter and the rover carry a suite of cameras and scientific instruments to study surface composition and magnetic fields.

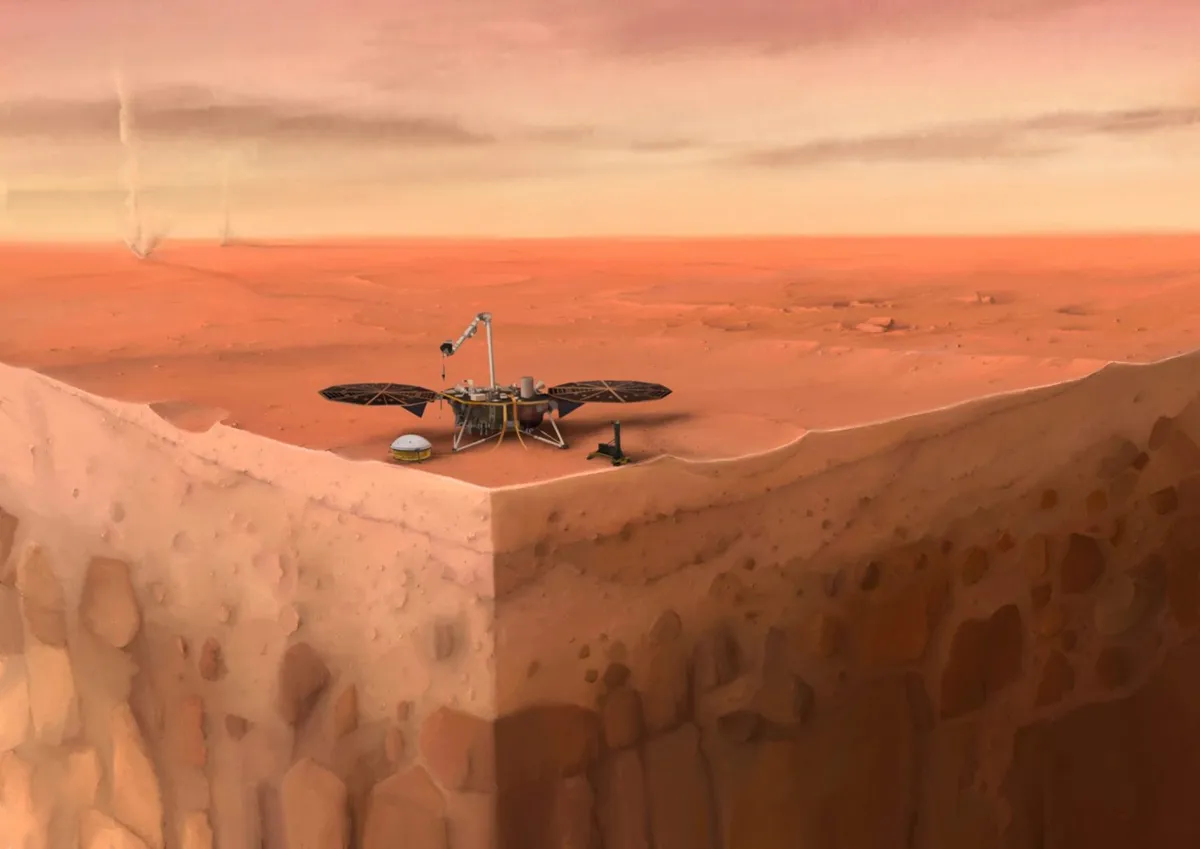

Scientists are particularly interested in the rover’s ground-penetrating radar instrument, which will map subsurface layers down to a depth of 100m.

NASA's Perseverance rover

By far the most versatile mission in the new Mars armada, however, is NASA’s plutonium-powered, one-tonne Perseverance rover.

Building on the experience (and the design) of Curiosity, which touched down on Mars almost eight years ago, Perseverance’s main mission is to study the habitability of the Red Planet and to seek signs of ancient life in the Martian rock record, according to deputy project scientist Katie Stack Morgan at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (for more on this, read our guide What makes a planet habitable?)

“I am optimistic that life could once have existed on Mars,” she says, “and Perseverance is well-equipped to search for – and hopefully find – potential biosignatures.”

Perseverance will launch on an Atlas V rocket from Cape Canaveral, with the window of opportunity beginning on 17 July 2020.

Like Curiosity, it will immediately dive into the Martian atmosphere, using novel autonomous technologies to make sure it lands precisely at the desired location.

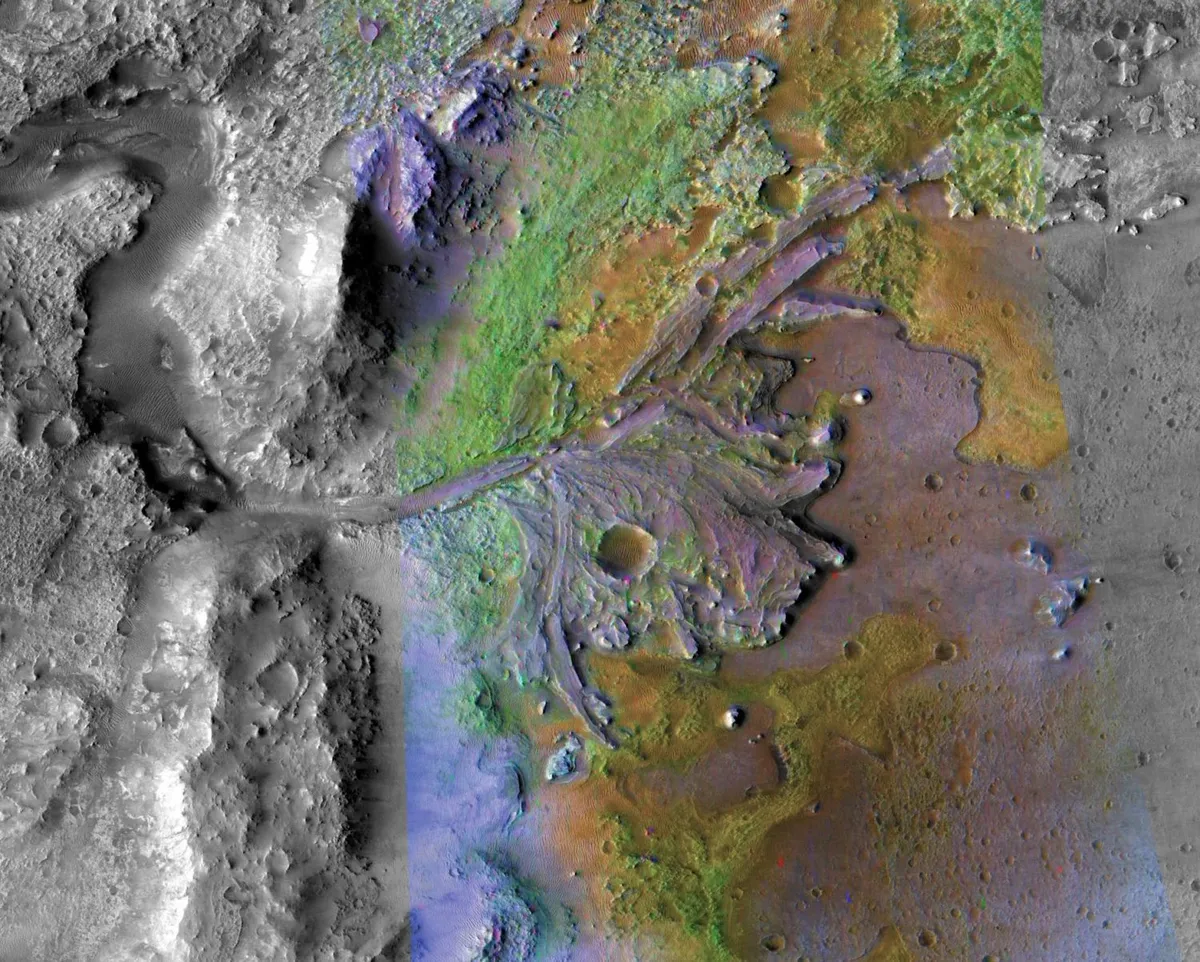

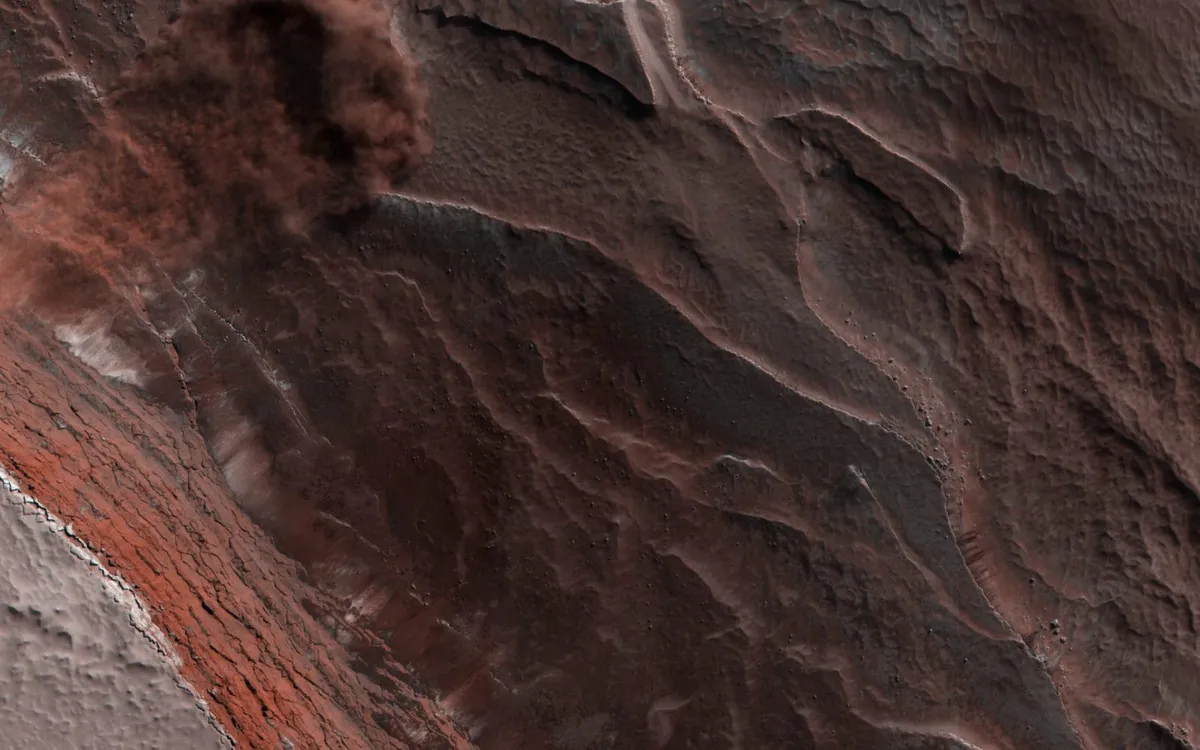

That spot is in the western part of the 50km-crater Jezero, close to a huge, fan-shaped ancient river delta. Scientists believe that Jezero once contained a lake, so it’s an ideal place to look for fossil evidence of microbial life.

What will the Perseverance rover do at Mars?

One of the main objectives of Perseverance is to take soil samples and to prepare them for future return to Earth but according to Stack Morgan, the rover’s own instruments also have the potential to make breakthrough discoveries.

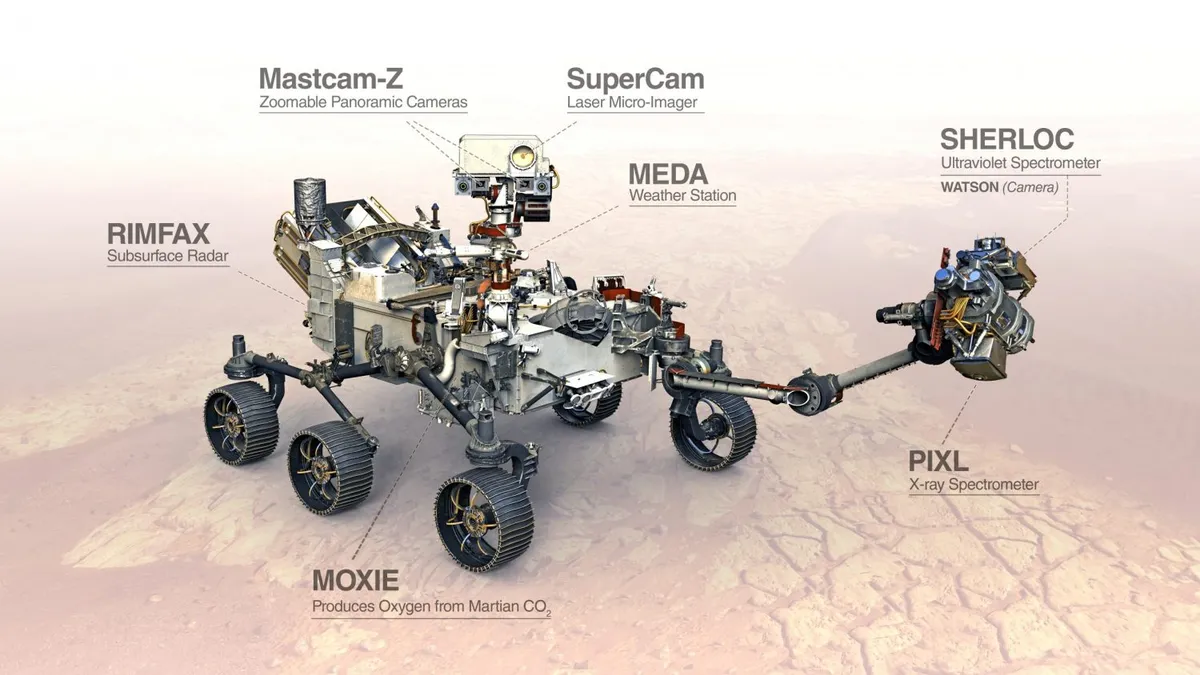

This is especially true for PIXL (Planetary Instrument for X-ray Lithochemistry) and SHERLOC (Scanning Habitable Environments with Raman and Luminescence for Organics and Chemicals).

“At a very fine scale, they will map the geochemistry, mineralogy, distribution of organics, and compelling texture within the rocks,” she says. “These are the same strategies we use on Earth to search for signs of life in our own rock record.”

Apart from PIXL and SHERLOC, which are located on the rover’s robotic arm, Perseverance’s instruments include a weather station (MEDA), a ground-penetrating radar (RIMFAX), and a technology demonstrator experiment to extract oxygen from the thin, carbon dioxide-rich Martian atmosphere (MOXIE).

In addition, the rover carries no less than 23 cameras. Most of these are relatively simple, black-and-white navigation and hazard avoidance cameras, but two cameras stand out.

SuperCam fires a laser at a distant target and uses spectrometers to study the resulting vapour, thus identifying the rock’s atomic and molecular make-up.

Mastcam-Z will routinely acquire 3D colour images of the surrounding landscape at various zoom settings.

"Mastcam-Z can see features as small as a house fly, all the way from a distance that’s about the length of a soccer field," says Mastcam-Z principal investigator Jim Bell, who is based at Arizona State University.

"The high-resolution stereo views provided by the twin cameras will be used to assess potential paths for the rover to traverse, and to create digital terrain models for scientific uses," he adds.

Both SuperCam and Mastcam-Z are mounted on the rover’s 2m-tall mast. Incidentally, Mastcam-Z will also be able to shoot high-definition video. Moreover, the rover carries two microphones – a first on any Mars mission.

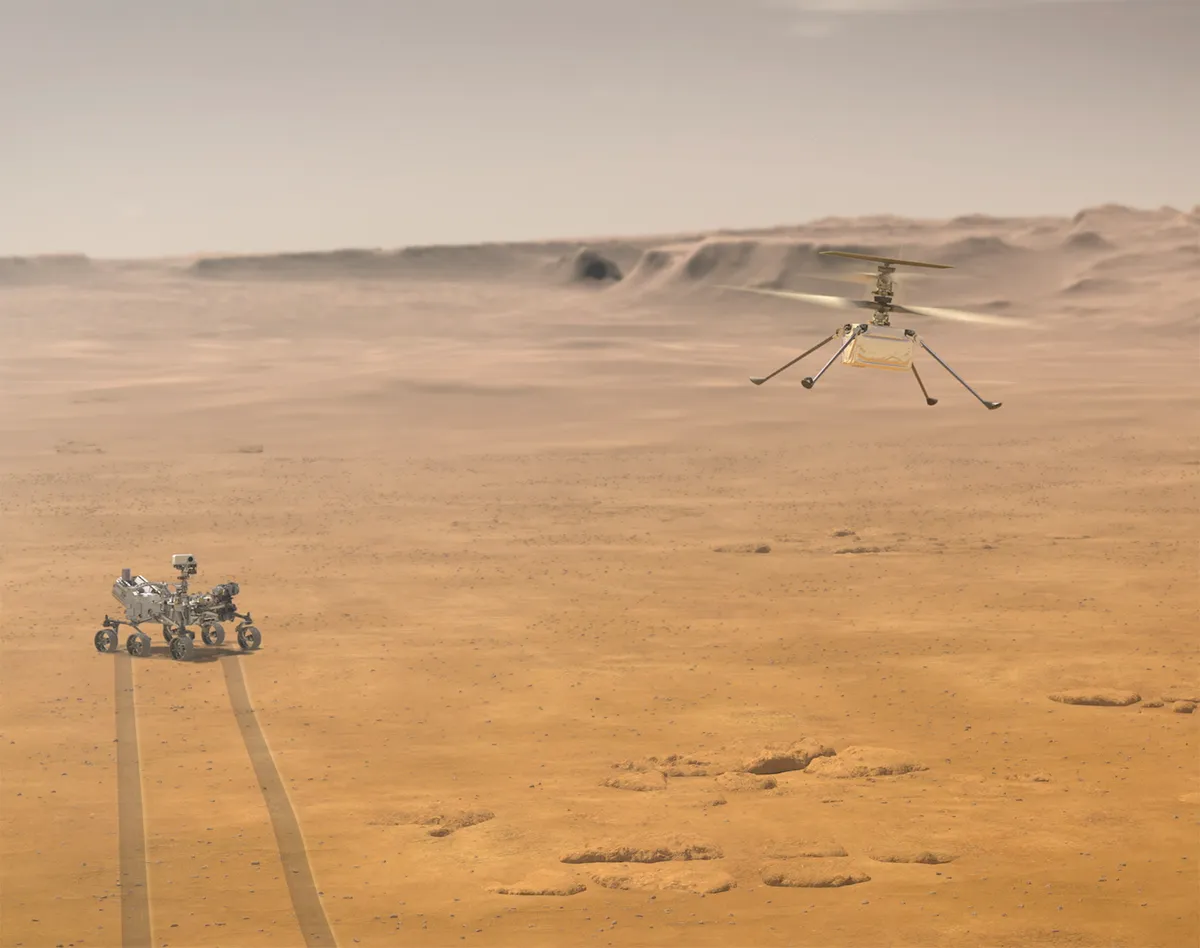

Even more exciting is the small, 2kg-helicopter on board Perseverance. Called Ingenuity, the twin-rotor, drone-like device is powered by solar cells and is equipped with a small camera.

Over a period of 30 days, engineers plan to carry out 90-second test flights in the thin Martian air, up to an altitude of 5m or so.

If all goes well, it may later attempt longer and higher excursions. There’s no science involved here; Ingenuity is a technology demonstrator to see how feasible future aerial Martian explorers might be.

NASA’s new Mars mission is bound to inspire the general public back on Earth. Imagine seeing footage shot while Perseverance drives across the Martian surface; listening to the sound of the wind in the thin atmosphere, the whirring of the rover’s instruments, and the ‘pop-pop-pop’ sounds of its SuperCam laser while an ingenious onlooker watches from above.

Planetary scientists, geologists and astrobiologists alike look forward to the wealth of new data that awaits them, not just from Perseverance, but also from Hope and Tianwen-1.

The 2020 Mars armada constitutes an important extension to the current fleet of operational orbiters, landers and rovers, and there’s even more to come in the future.

As Bell says: “The challenge is to solve the Red Planet’s mysteries and to help the future spacecraft, and – eventually – people that will be heading out to Mars.”

When will the Rosalind Franklin rover launch?

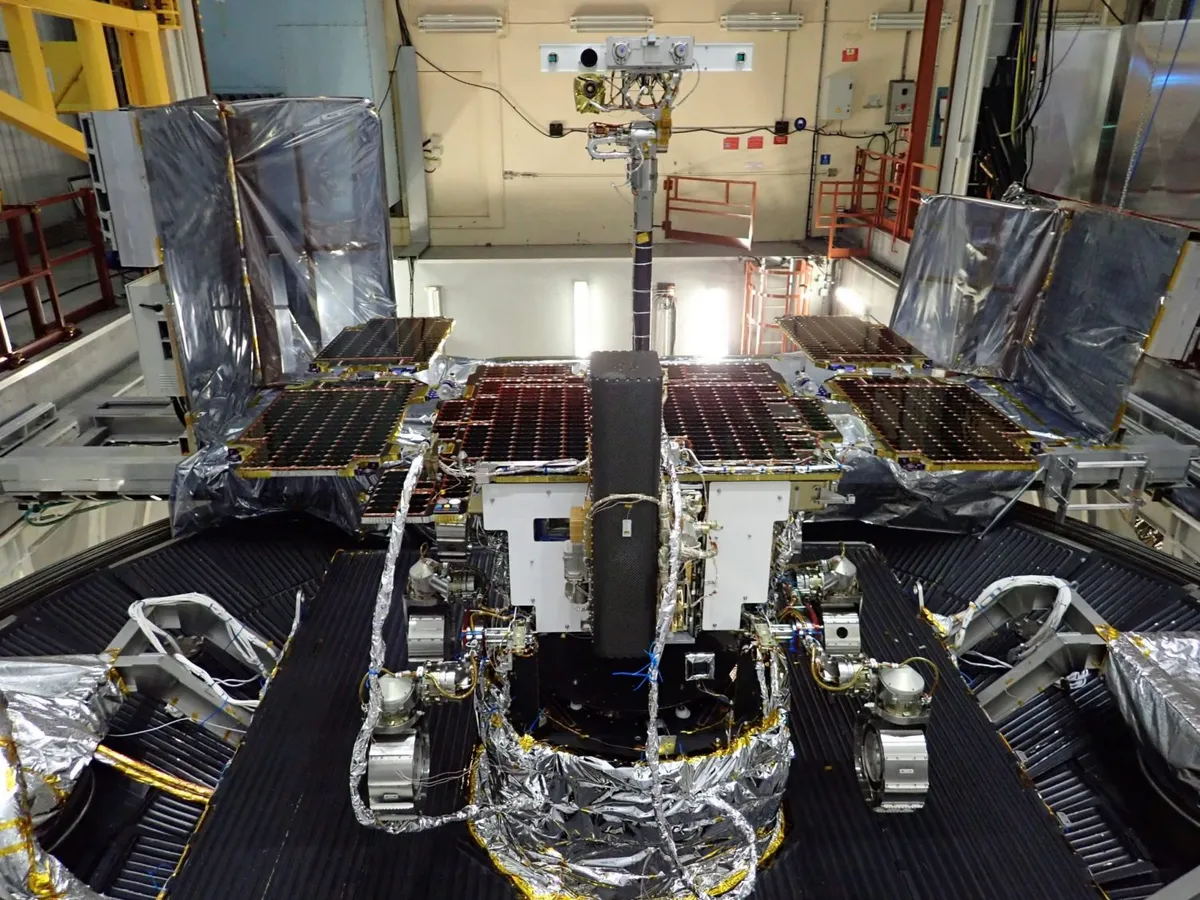

The European Space Agency’s (ESA’s) Rosalind Franklin rover has been beset with problems, predominantly with its giant parachutes.

While these issues have now been solved, says project scientist Jorge Vago, they couldn’t be executed in time for the launch – partly due to travel restrictions imposed by COVID-19.

“As it is, the earliest we will be able to execute these tests is late September 2020,” says Vago.

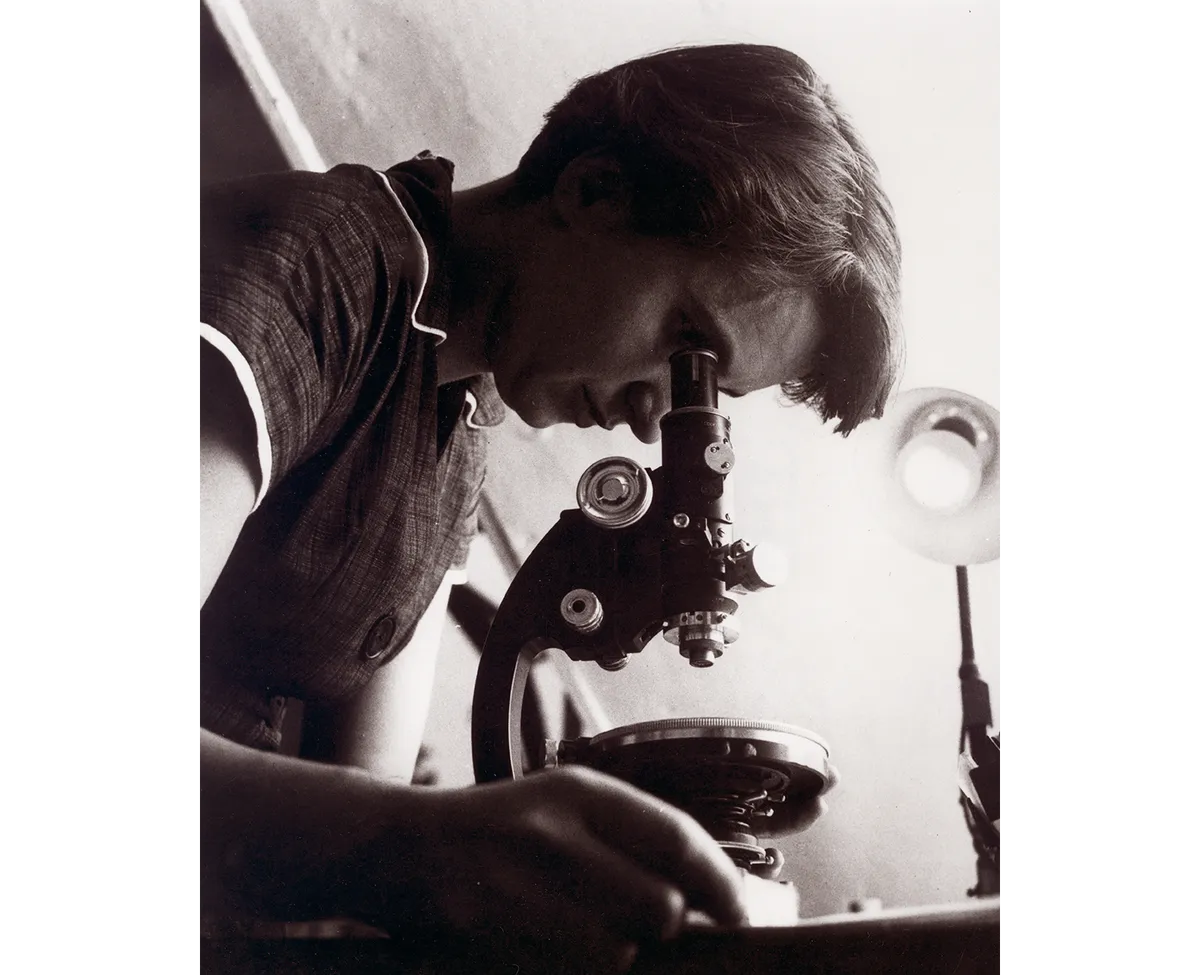

Rosalind Franklin – named after the British co-discoverer of DNA – is part

Russia is providing the Kazachok lander that will deploy the rover to the surface and the Proton-M rocket which will launch it in September 2022, aiming for an arrival in spring 2023.

According to Vago, the project’s delay provides an opportunity to carry out a few improvements to the rover, such as replacing one of the spectrometers with

a better-performing spare, upgrading software and electronics, and reinforcing the hinges of the solar arrays.

Once on Mars, Rosalind Franklin will use its 2m-drill to go beneath the Martian surface and search for biosignatures of past Martian life.

Alongside this are cameras, microscopes, spectrometers and an organic molecule analyser.

The rover will work alongside the first instalment of the ExoMars programme, the Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO), which has been at the Red Planet since 2016, to gain a complete picture of what Mars is like.

“The good new is that TGO is doing great,” says Vago, “And we have fuel for more than 20 years.”

The Mars sample return mission

One of the most important tasks of NASA’s Perseverance rover is to collect soil samples and prepare them for a future return to Earth, where geologists and astrobiologist can study them in fully equipped terrestrial laboratories.

“It’s thrilling to think that these samples have the potential to lead to major, possible paradigm-shifting discoveries about Mars, our Solar System, and life beyond Earth,” says deputy project scientist Katie Stack Morgan.

Perseverance will seal the precious material – pebbles, soil and atmosphere – in some 40 titanium capsules that will be left at a small number of recovery spots, to be collected by a future space mission – probably a NASA/ESA collaborative effort.

This new, as-yet undefined (and un-funded) mission will comprise an orbiter, a lander, a small rover, some sort of capsule launch mechanism, the retrieval of the capsules in Mars orbit, a return flight to Earth, and a parachute drop of the container carrying the samples.

Given the necessary time to develop this complex mission, and the infrequent launch windows for a flight to Mars, it’s unlikely that scientists will have ‘fresh’ samples from the Red Planet under their microscopes before the early 2030s.

Mastcam-Z’s principal investigator Jim Bell, says: “For me, the idea of being able to help identify and select these samples is super exciting.”

Govert Schilling is is an astronomy journalist and broadcaster, and author of Ripples in Spacetime.

This article originally appeared in the August 2020 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.