The Space Race began in earnest on 4 October 1957, when the Soviets launched Sputnik, the world’s first artificial satellite. Sputnik I orbited Earth roughly once every 96 minutes and was tracked by Soviet scientists for about 21 days, before its batteries died on 26 October 1958.

The USSR had begun the race to conquer space. On 4 January 1958, Sputnik I fell back towards Earth, burning up on re-entry into Earth's atmosphere, but by that stage the Soviets had already launched Sputnik II on 3 November 1957, carrying the dog Laika into Earth orbit.

The Soviets has shown it was possible to put animals in space, and from that day forward the launch of human beings seemed more of a possibility. Now it was up to the USA to show that they could compete with the space-faring successes enjoyed by the USSR

Sergei Korolev

Perhaps the most important figure in the Soviet space programme - indeed the Space Race as a whole - was Sergei Korolev. Without his leadership, the USSR may not have enjoyed the gains they made so early on.

Sergei Korolev’s greatest creation was the dual-purpose R-7 missile, or Semyorka (‘Little Seven’) as it was affectionately known by the men who built it.

Fuelled with liquid oxygen and kerosene, and incorporating four drop-away boosters parallel to a central core, it was the world’s first intercontinental ballistic missile. The development of rockets for space was, at that time, a by-product of creating the instruments of warfare.

The lower stages, or ‘blocks’, of the vehicle were fitted with engines designed by Valentin Glushko. His compact turbine fuel pumps and clever pipework serviced four combustion chambers simultaneously.

The apparent thrust of 20 separate engines on the R-7 was, in fact, delivered by just 5, each of which had 4 nozzles. This rugged and reliable rocket was the basis for the Soyuz boosters that still carry modern Russian capsules to the International Space Station today.

The first two launches of the R-7 had failed, but in August 1957 it flew a simulated nuclear strike mission over Soviet territory and, just weeks later, began its career as a space rocket.

These early successes were the result of Korolev’s cunning, explains space historian Andy Aldrin, the son of Apollo 11 astronaut Buzz.

"The people who were running the missile programmes owed their careers to him, so they were reluctant to take him on. Many of them didn’t really understand rocket technology, and they had to trust him."

Sergei Korolev’s power had been consolidated by the triumph of Sputnik in 1957, and he was urged by the Kremlin to create yet more space spectaculars with the R-7.

He had to avoid clashes with military chiefs who insisted that the R-7 should be devoted to defence. Korolev tempted them with the idea of spy satellites that could reveal America’s secrets from orbit.

But first, he said, Russia should launch human pilots with excellent eyesight, to report on what spy cameras might see.

The Kremlin swallowed Korolev’s trick but its support for his orbital adventures came at a price, putting great strain on his health. He was pushed to work faster and come up with new triumphs.

America, though, had been spurred into action by Sputnik. NASA was formally created in 1958 and inherited ideas for human spaceflight from its smaller, precursor organisations.

The most fully realised project was Mercury. It comprised a tiny, cone-shaped capsule that would ride on the top of Redstone – a small battlefield missile. Redstone was closely based on Wernher von Braun’s notorious V-2 rocket from the Second World War.

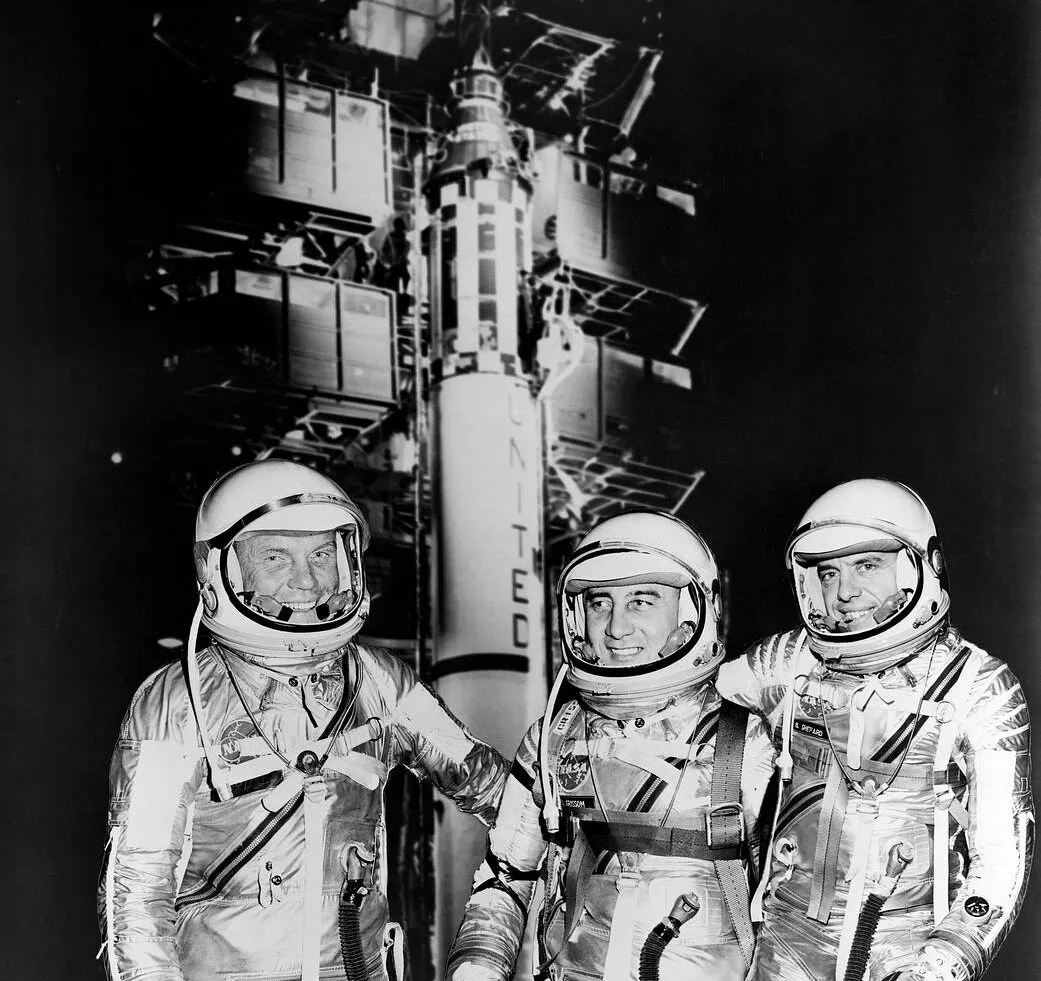

Many in America doubted the usefulness of adventure for adventure’s sake, but in April 1959, NASA announced the selection of the Mercury 7 astronauts.

Unfortunately for them, Korolev was ready with his Vostok spacecraft, and Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin beat NASA astronaut Alan Shepard into space by just 3 weeks.

The era of crewed spaceflight begins

The Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev positively crowed after Yuri Gagarin’s 108-minute orbital flight: "Let the whole world look and see what our great country is capable of. Let the capitalist countries catch up with us!"

Over in the US, project Mercury was intended to do just that. It had been the ‘man-in-space-soonest’ project until it transferred from the US Air Force to a newly established NASA.

After flying a chimpanzee called Ham in January 1961, Mercury had almost placed an astronaut into suborbital space ahead of Gagarin’s 12 April flight. In the event, lingering safety fears meant its 24 March launch was unmanned.

After Gagarin, the race was really on. In the two extraordinary years that followed, cosmonauts and astronauts became what Tom Wolfe, author of The Right Stuff, termed ‘single combat warriors’.

It was, he wrote, an elaborate ritual challenge between warring tribes. They climbed to the top of elongated bombs where they encased themselves in metal capsules to be fired into the vacuum.

American rocketry laboured at a disadvantage: the Soviets had the powerful R-7, an intercontinental ballistic missile initially designed to fire hydrogen bombs at American cities.

The Russian physicist Andrei Sakharov had been asked how much future H-bombs were likely to weigh. His back-of-the-envelope estimate was 5 tonnes, so that became the R-7’s payload. In fact, actual bombs weighed nothing like as much, but Soviet space engineers made the most of this surplus capacity.

Designed for daintier warheads, US rockets ended up smaller and, as a consequence, so did their spacecraft.

The Mercury capsule

"You didn’t get into the Mercury capsule, you wore it," explained astronaut John Glenn. The capsule had a blunt cone and the habitable volume of a telephone box – it could have fitted inside a Space Shuttle engine nozzle.

So crammed was it with instrumentation that pilots sometimes pressed the wrong switches by accident. But astronauts themselves helped in the Mercury design process, insisting on being active pilots rather than simply ‘spam in a can’, as some had witheringly described them.

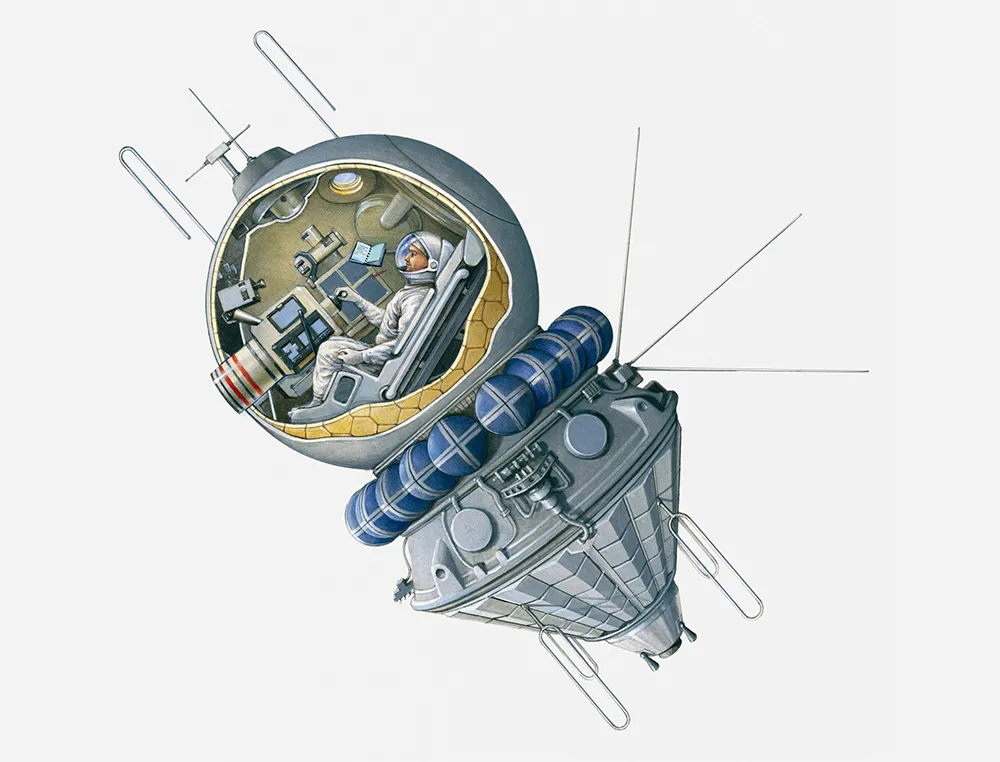

The Vostok capsule

In contrast, cosmonauts sat back as passengers, only taking control of their Vostok spacecraft in an emergency. Their padded capsule was streamlined, with a bare minimum of gauges and controls, with subsystems housed in a module of their own.

Two-thirds larger than its Mercury rival, Vostok was also far roomier. Vostok’s single cosmonaut sat within a 2.4m-diameter aluminium sphere covered by ablative shielding.

This descent module was connected to a cylindrical instrument module that housed all spacecraft subsystems and retro-rockets, and was separated from the main craft before re-entry.

The Vostok’s occupant slid through a round hatch to sit in their ejection seat. Instrumentation covered a minimal part of the otherwise padded interior – cosmonauts were not expected to play an active flight role – while three portholes fitted with blinds offered exterior views.

While the Vostok’s manned spaceflight career ended in June 1963, hundreds of unmanned variants flew during succeeding decades, including reconnaissance Zenits and scientific Bion, Resurs and Foton capsules.

Lacking the re-entry manoeuvring of Mercury capsules, the Vostok descent module was spherical and could re-enter the atmosphere in any configuration.

And because it came down on land instead of over the ocean, cosmonauts were ejected automatically 7km up, parachuting the rest of the way.

Not that early US astronauts did much active piloting. The first two Mercury flyers were launched on a Redstone booster – a next-generation V-2 – on a modest suborbital trajectory, tracing a 15-minute ballistic curve from Cape Canaveral to the Bahamas.

The first American in space

On 5 May 1961, Alan Shepard became the first American in space, reaching a maximum altitude of 187km aboard Freedom 7 and experiencing five minutes of weightlessness in the process.

Shepard fired his thrusters and braking rockets but, as the Apollo 13 crew later remarked, Isaac Newton did the real driving.

Unlike Soviet space shots, the mission was undertaken in the full glare of publicity. Shepard had felt impelled to satisfy popular expectations, remarking on a "beautiful view" through his periscope (this early Mercury lacked a decent window)

On his safe return, Shepard enjoyed ticker-tape parades and received a White House medal. But Gus Grissom, whose Liberty Bell 7 launched 77 days later on 21 July 1961, fared less well.

Grissom’s flight went fine, but after splashing down in the Atlantic his exit hatch blew open, flooding the capsule. Liberty Bell 7 sank to the ocean floor (it was eventually salvaged in 1999) and Grissom came close to drowning inside his spacesuit.

For the short remainder of his life, Grissom felt under suspicion of blundering. Tragically, he perished in the Apollo 1 fire of 1967.

Further suborbital flights were scheduled...until the Soviets flexed their muscles. On 6 August 1961, Gagarin’s back-up Gherman Titov followed his comrade up on Vostok 2.

Just 25 years old and the youngest person to fly in space, Titov stayed up for an entire day of 17 orbits. He took a movie camera into space and manually turned his spacecraft on its axis.

On his last orbit, Titov’s retro rockets triggered automatically and he experienced a bumpy re-entry because the Vostok’s instrument module failed to completely disengage, as had happened to Gagarin.

In response, NASA prioritised its more powerful Mercury-Atlas launcher. Enos, a chimpanzee, tested the ride to orbit that November, but technical snags delayed John Glenn’s follow-up flight until 20 February 1962.

Glenn’s Friendship 7 hurtled east with an orbital velocity of 28,000km/h – some 3.5 times faster than his suborbital predecessors – for three orbits of Earth.

The former marine then switched his capsule forward in the direction of flight, savouring the view, but reported mysterious 'fireflies' swarming.

Malfunctioning automatic controls induced a slight drift, but manual compensations were too fuel-hungry to continue. More seriously, a sensor alerted ground control that Glenn’s heat shield may be coming loose. If so, he would be incinerated on re-entry.

Wary controllers told Glenn not to jettison his retro-rocket pack as usual, hoping its straps would keep the shield in place. Glenn heard molten fragments of retro-rocket bump against his hull, but completed his descent safely (the sensor was faulty).

Scott Carpenter’s Aurora 7, launched on 24 May 1962, was another three-orbit flight, this time focused on science objectives. Carpenter observed terrestrial features, sunrises and sunsets and atmospheric skyglow.

He tried (and failed) to inflate a balloon out of his capsule’s nose to measure vestigial atmospheric drag. He also solved the mystery of Glenn’s fireflies: a knock on the hull sparked their reappearance, so Carpenter realised they were ice particles.

But a distracted astronaut had burned a lot of fuel and was forced to make a manual re-entry, with splashdown 463km off target. It took an anxious 45 minutes to find out that he’d returned safely, but he never flew in space again.

The Soviets surge ahead yet again

As NASA vowed to do better, its Soviet rival scored another spectacular. On 11 August 1962, Andrian Nikolayev launched to orbit on Vostok 3, followed into space the very next day by Pavel Popovich aboard Vostok 4.

At their closest, the two spacecraft were 6.5km apart. Astonished Western experts wondered if the pair might attempt docking – not knowing that Vostok, like Mercury, could not alter its orbit.

The two Vostoks gradually drifted apart over the course of three days in space. These cosmonauts were the first to slip their straps and float freely, and Nikolayev performed the first live TV broadcast from orbit.

But both spacecraft grew uncomfortably cold and humid and the cosmonauts came home after 94 and 71 hours respectively.

Wally Schirra’s nine-hour Sigma 7 flight on 3 October 1962 seemed comparatively pedestrian, although he faced a novel danger: a high-altitude nuclear test had pumped up radiation levels. Thankfully, they were above Schirra’s maximum altitude.

He even successfully managed to deploy the inflated balloon that had evaded Carpenter, and system refinements meant he re-entered with more than half his onboard fuel left.

Next, NASA eyed a long-duration mission. On 15 May 1963, Gordon Cooper began an intended three-day flight – only to be forced down in less than half that time.

He was notably relaxed, falling asleep on the launch pad and using up much less oxygen than his predecessors – supposedly because he was the first non-smoking astronaut.

Cooper hosted the first (snowy) US TV broadcast from orbit, deployed a strobing microsatellite for visibility tests. He also made scarcely believable observations of the ground – tracing chimney smoke back to a single Tibetan cottage, for instance.

Cooper’s spacecraft fared worse than he did – its cabin temperature and carbon dioxide levels crept up. On his 19th orbit, an alarm falsely indicated that Faith 7’s orbit had dropped and its electrical system began to fail.

Automatic control systems and attitude readings stopped working and then telemetry – though not radio contact – was lost. Attitude readings failed; even the onboard clock stopped.

Cooper was ordered to take amphetamines to ensure his alertness for what came next. Steering against the stars and timing with his wristwatch, Cooper undertook a mechanical manual re-entry. Astonishingly, Faith 7 landed just 7km from the recovery ship.

Further three-day flights were discussed, but Cooper’s experience convinced planners they had hit the Mercury capsule’s limits. NASA then moved to its next-generation two-man Gemini, and then to the three-man Apollo spacecraft.

Space single ‘combats’ were almost over – with one last flourish. On 14 June 1963, Valery Bykovsky launched on Vostok 5. He was followed two days later by Valentina Tereshkova – the first woman in space – on Vostok 6.

It was another Soviet propaganda coup, although Tereshkova, a factory worker and amateur parachutist, was reportedly distressed and ill during her flight.

Despite steadily falling cabin temperatures, Bykovsky had a better time, setting a five-day record for lone spaceflight. It is a record unlikely to be broken, as solo flights were by then at an end in the USSR as well.

The first manned spacecraft had simply to prove that people could survive in space. “We didn’t really contribute very much to the flight of the vehicle,” conceded Mercury astronaut Wally Schirra. “We were lab specimens.”

With the Mercury and Vostok spacecraft, a solitary pilot could manually rotate them but not change their flight direction, except to fire retro rockets that braked them out of orbit altogether.

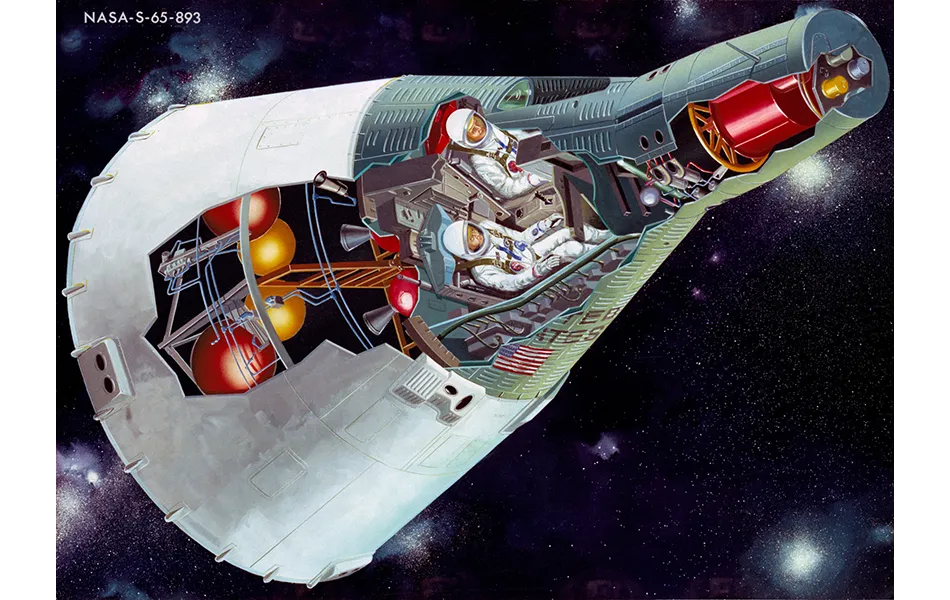

The Gemini program

Once it was proven that people could indeed survive in space, having them do useful work was the logical next step. This would require many people, not solo flyers, because it would take more than one crewman to master the techniques needed to go to the Moon.

This essential Apollo to-do list included changing orbits, extended spaceflights, rendezvous and docking, and extra-vehicular activity (EVA) – spacewalks.

On the American side, a modest two-man Mercury Mark II concept ended up as the fully fledged Gemini programme. Smarting over the loss of his Liberty Bell 7 spacecraft, astronaut Gus Grissom was determined to fly in space again.

So he worked closely with the Gemini team, applying his experience to its design. The result was what other astronauts called the ‘Gusmobile’ – a craft so closely designed around Grissom that its seats needed enlarging to accommodate taller occupants.

Over a frenzied 30 months, the first true spacecraft took shape. Gemini had thrusters for active piloting and carried the first onboard computer to calculate orbital mechanics.

Gemini was twice as heavy as Mercury and needed to be launched on the powerful Titan II rocket.

For astronauts it was cramped, having just 50% more cabin space than Mercury, but it appeared less cluttered because its subsystems were in a dedicated equipment module, with the thrusters housed in the hindmost section. Only the astronauts’ re-entry module returned at the end of the mission.

Instrumentation followed a cockpit-style configuration. Gemini’s Canadian design team had been responsible for the legendary Avro Arrow jet and borrowed concepts from fighter planes.

They included stick controllers, rendezvous radar, access hatches for easier maintenance and ejection seats to replace Mercury’s launch escape tower.

A wary John Young witnessed one ejection seat test in which Gemini’s cabin hatch stayed shut. "That’s one hell of a headache – but a short one!" he quipped, drily.

Meanwhile, the USSR was developing its own Gemini equivalent: the three-man Soyuz (Russian for ‘Union’). The initial plan involved docking a trio of Soyuz spacecraft in Earth orbit, forming a ‘space train’ to head to the Moon.

But the Soviet effort was under-resourced and, in reality, Soyuz was years away from flying. The USSR’s lead in the Space Race was about to vanish, so Chief Designer Sergei Korolev took a reckless gamble.

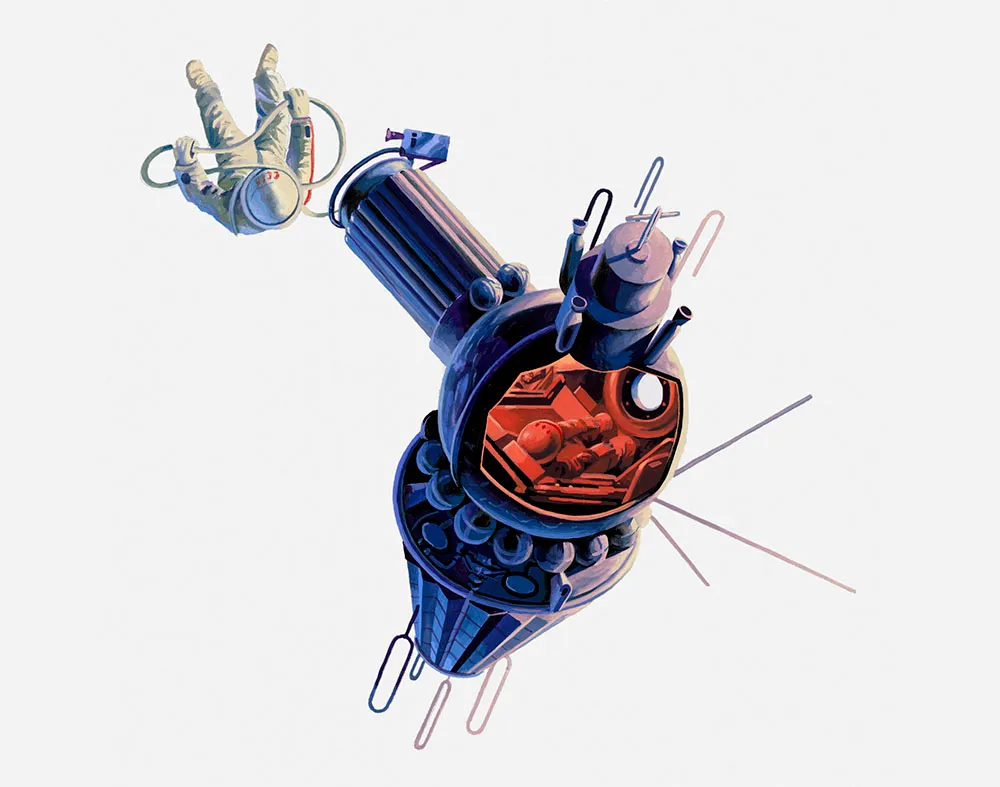

Voskhod and the first spacewalk

On 12 October 1964, six months after America’s first, unmanned Gemini test flight, Moscow announced the launch of a brand new spacecraft called Voskhod (Russian for ‘sunrise’).

It had not two but three crew members – Boris Yegorov, the first doctor in space, engineer Konstantin Feoktistov and pilot Vladimir Komarov.

Voskhod’s 24-hour flight achieved another propaganda coup, but in truth the craft was no great leap forward. Korolev had simply crammed the trio into a modified Vostok.

To fit in, they wore wool garments instead of spacesuits and their ejection seats were replaced with a retro-rocket touchdown system. The hurriedly fitted Voskhod couches were at right angles to the original layout, so the cosmonauts had to crane their necks to read instruments.

They could barely move in the cramped cabin, which became uncomfortably hot and humid. An anxious Korolev could hardly believe it when Voskhod 1 made it down safely.

A two-man Voskhod 2 followed on 18 March 1965, five days before the first manned Gemini mission.

"The sailor on the ship should be able to swim," declared Korolev, in advance of what was to be the first spacewalk. An inflatable airlock was extended from the capsule and Alexei Leonov became the first human to spacewalk, floating in space for 12 minutes.

Officially the spacewalk was a success. In reality, his spacesuit had ballooned until movement became impossible. Leonov had to reduce its pressure by a third to squeeze back inside the airlock, almost suffering heatstroke in the process.

Cosmonaut Pavel Belyayev helped the exhausted Leonov back inside. They ejected the airlock as planned but the hatch didn’t seal properly.

Pure oxygen pumped in automatically to compensate, posing a fire risk. Then their automatic re-entry guidance system failed.

Performing manual re-entry meant leaving their couches to reach the controls, then clambering back to preserve the Voskhod’s delicate centre of gravity.

They plummeted down, far off course, and it was two days before they could be rescued from thick Siberian forest. Korolev had tentative plans for Voskhod 3, but he died in January 1966.

The launch on 23 March 1965 of Gemini 3 with Gus Grissom and John Young (the first of the astronauts dubbed the ‘Next Nine’ following the Mercury 7) was thoroughly overshadowed by Russia’s success, despite it performing history’s first ever orbital change.

But over the nine Gemini missions that followed, it became clear that the US was opening up a decisive technical lead. Gemini 4, on 3 June 1965, bore witness to Ed White’s 22-minute spacewalk. And August’s Gemini 5 was an eight-day mission, made possible with onboard fuel cells replacing batteries.

Gemini 8: the first docking in space

Gemini 7, launching on 4 December 1965, was Jim Lovell and Frank Borman’s long-duration mission. Borman famously described it as "Spending two weeks eating, sleeping, working and going to the bathroom stuffed into the front seat of a sports car wearing an overcoat."

The dry atmosphere induced runaway dandruff, plus the pair had to share a toothbrush when one drifted away.

Their spacecraft served as a rendezvous goal for Gemini 6A, which finally launched out of sequence on 15 December. The computer guided Wally Schirra and Tom Stafford though 35,000 separate thruster firings to home in on Gemini 7. This was the real thing.

Vostok 3 and 4 had been placed into adjacent orbits during their supposed 1962 ‘rendezvous’ but had soon drifted apart, like cars driving parallel on divergent highways.

In contrast, the two Geminis came as close as 30cm and kept station for more than five hours. Both spacecraft were seen to have booster cords dangling untidily behind, accounting for the mysterious clanging sounds heard on previous missions.

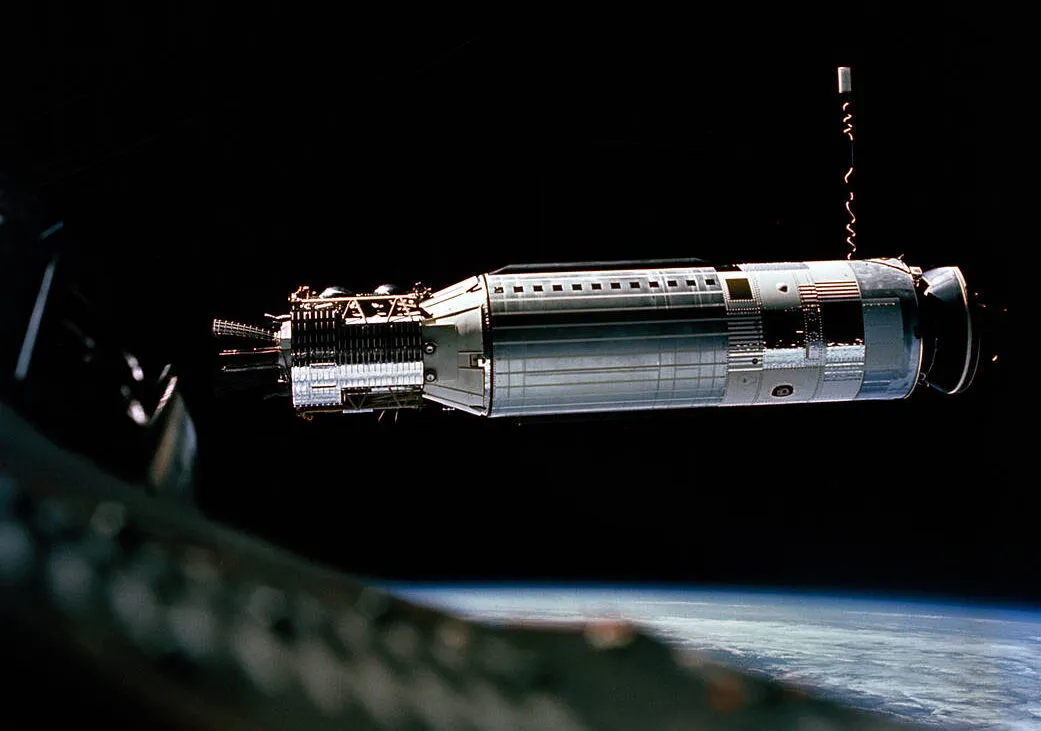

The next step was docking. On 16 March 1966, Gemini 8 closed on its orbital target: an unmanned Agena booster. Within 6.5 hours of launch, Neil Armstrong and Dave Scott had docked, but then the combined vehicle began tumbling through space.

A concerned Armstrong separated them, but the Gemini began spinning even faster. At one turn per second, their vision blurred – they were in danger of blacking out. But Armstrong stayed cool.

He realised the spin must come from a faulty Gemini thruster, not Agena. He deactivated all attitude thrusters and fired the re-entry thrusters to bring the spacecraft back under control.

This setback meant a scheduled spacewalk was cancelled, but Gemini 9A, flown on 3 June, included an ambitious foray into space. Eugene Cernan climbed to the back of the Gemini to fly an Air Force-designed manoeuvring jetpack.

That was the idea, at least, but Ed White had made it look too easy. Cernan struggled against his rigid suit and couldn’t control his movements.

His visor fogged up as his struggles exceeded the capability of the suit’s cooling system. Effectively blinded, Cernan’s spacewalk was curtailed and the jetpack abandoned.

He felt his way back to the hatch, having lost over 4kg in weight during the two-hour spacewalk, his back burned in places by torn insulation that had let sunlight through.

Launching on 18 July, Michael Collins was Gemini 10’s spacewalk guinea pig. His first involved simply standing up in the hatch; the second was to collect experiment packages from the side of a docked Agena.

Collins used the same ‘zip gun’ as Ed White but still showed a lack of control that sent the Agena into a spin. He pulled himself back along his umbilical but while securing himself, Collins lost the camera recording his EVA.

More successfully, the Gemini 10 crew fired their docked Agena’s thrusters to take them to a second Agena, left over from Gemini 8.

Gemini 11, flown on 12 September 1966, repeated the trick, rocketing up to a record-breaking 1,374.1km. "The world’s round!" confirmed a happy Pete Conrad.

Earlier, Dick Gordon’s walk hadn’t gone so well: he ended up exhausted just placing a camera. He managed to attach a tether to the Agena but, like Cernan, was blinded by a fogged-up visor.

The tethered Agena was put into a spin to create artificial gravity in space for the first time. The effect was tiny – not enough for the astronauts to feel but just sufficient to propel a camera towards one end of the spacecraft.

On the final Gemini 12 mission on 11 November, Jim Lovell had ‘The’ written on the back of his suit, and Buzz Aldrin had ‘End’ on his.

They docked with an Agena on their first orbit before lining up to observe a total solar eclipse, showing how much skill had been gained.

A spacewalk was the last, stubborn challenge. In preparation for the flight, Aldrin had practiced extensively underwater in NASA’s new Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory and the newly designed foot restraints, dubbed ‘golden slippers’ helped by keeping him braced in place so that he could comfortably achieve all his spacewalking goals.

After four days in orbit, the final Gemini splashed down within 5km of its main recovery vessel. There were proposals to fly more – a lunar orbit was one idea – but NASA believed Gemini had achieved its objective, amassing practical experience that could be used in the lead up to Apollo 11.

Now, the way to the Moon was clear, and the Apollo programme could begin.