On 11 April, 13:13 Houston time, Apollo 13 set off for the Moon. Little did NASA and the astronauts on board know that they would soon be embarking on one of the most incredible rescue missions in the history of humanity. And yet problems began before Apollo 13 had even lifted off.

It was the evening of 25 March 1970 and the Saturn V that would soon carry Apollo 13 to the Moon cast a long shadow across launch pad 39A.

Security guard Earl Paige was sitting in his car, about to drive off but as he turned the key, his car burst into flames.

The engine’s heat had ignited a cloud of oxygen dumped from the Saturn V’s fuel tanks. Paige was pulled from the fire unharmed, but this wasn’t the last time an oxygen tank would cause problems for the ill-omened Apollo 13.

More about the Apollo era:

- Listen to our Apollo 13 podcast

- The Apollo missions that might have been

- Apollo conspiracy theories debunked

During pre-flight briefings, commander Jim Lovell waved off concerns that a mission numbered ‘unlucky 13’ was destined to suffer misfortune – to his Italian forefathers, 13 was an auspicious number.

But the press was desperate for a new angle on the Apollo missions, which the public were already growing tired of.

The press got their dose of bad luck for the mission a few weeks before launch. Lovell’s son had German measles, as did back-up lunar module pilot Charles Duke.

An astronaut getting sick at the Moon would be a disaster, so NASA tested the crew to see who was immune. Lovell and lunar module pilot Fred Haise were. Command module pilot Ken Mattingly was not.

Mission Control were forced to split the crew – something they’d sworn never to do – and swapped Mattingly for back-up pilot Jack Swigert.

Five and a half minutes into the flight, Lovell felt the rocket rattling more than it had done on his previous flight with Apollo 8.

The central engine of the S-II stage’s five thrusters had shut down early but the computer compensated.

Lovell breathed a sigh of relief. Every Apollo mission had at least one major crisis, so he was relieved Apollo 13’s was out of the way early. From now on it should be smooth sailing.

It was 13 April, 9.05pm local time in Houston (14 April, 03:07 UT), 55 hours and 52 minutes into the mission and Apollo 13 was 322,000km from home.

A handful of staff were left on duty at Mission Control, trading jokes about how dull the night shift was.

“13, we’ve got one more item for you when you get a chance,” said Jack Lousma, acting as CAPCOM, the relay between Mission Control and the crew. “We’d like you to stir up your cryo tanks.”

It was an innocuous order – the crew had already stirred the tanks four times during the mission. The crew followed it without thinking.

A bang, like a crack of thunder, rang through the spacecraft.

On the control panel, an error message lit up: ‘Main bus B undervolt’. One of the two main electrical hubs had suffered an abrupt loss of power.

“Houston,” Lovell radioed down to the ground, “we’ve had a problem.”

Mission Control watched as the oxygen levels in Tank 2 plummed to zero. Slowly, Tank 1 began to follow suit. They were aware that these two tanks fed the three fuel cells onboard – without oxygen, there could be no power.

Hoping it might just be a glitch, Lovell glanced out the window.“We are venting something out into the – into space,” he said. It was their oxygen. The emergency was genuine.

Warnings lit up the control panel as system after system failed. They needed to stem the leak before their power was completely gone.

With two of the fuel cells already dead and the other dying, Mission Control chose a drastic course of action.

“We want you to close the REAC valve on fuel cell 3. You copy?” said Mission Control.

“…You want me to shut the REAC valve on fuel cell 3?” Haise queried. “Did I hear you right?”

Closing the valve would turn off the fuel cell. They would not be able to restart it. Whatever happened afterwards, the crew of Apollo 13 would definitely not land on the Moon.

“That’s affirmative.”

Haise followed the order but the oxygen in Tank 1 continued to fall. Mission Control feared Tank 2 had ruptured, nicking Tank 1 to create a slow but unstoppable leak. They needed to bring the crew home. Fast.

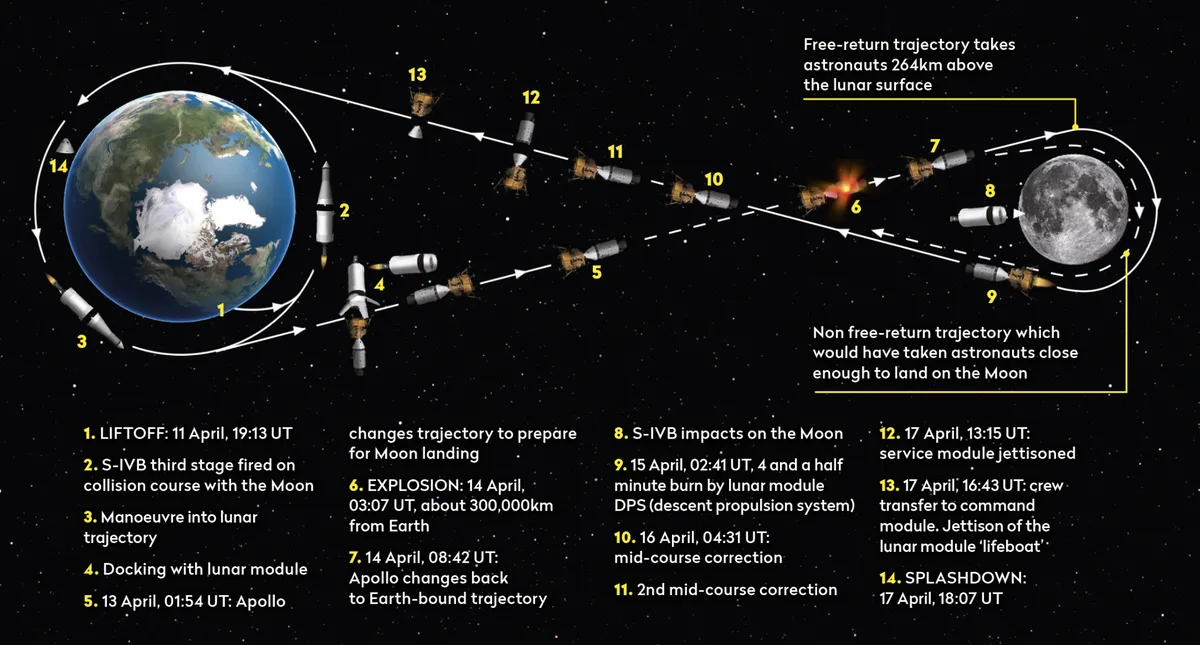

First choice was using the service module’s main engine to perform a U-turn, returning the crew to Earth within two days, but there wasn’t enough power.

The only other option was to somehow nudge the spacecraft so that it swung around the Moon, returning to Earth five days later.

With the direness of the situation setting in, both Mission Control and crew settled on a procedure intended for the grimmest of emergencies – using the lunar module, Aquarius, as a lifeboat.

With less than 15 minutes before the command module, Odyssey, ran out of power, Swigert had to turn off every system possible, while Haise and Lowell – the lunar module crew – were tasked with powering up Aquarius.

With one radio link to the ground, orders volleyed back and forth between the two teams, confusing the astronauts over which instructions were meant for who.

“13, You’re both talking at once,” Lousma reprimanded; too much haste could be as deadly as too little. “One at a time please.”

Well, I’m afraid this is going to be the last lunar mission for a long time.

Jim Lovell

Methodically, Swigert shut down Odyssey until it was quiet as a tomb. The command module pilot left his charge behind and crossed over into Aquarius, a vehicle he was never meant to enter, on a mission he was never meant to fly, with colleagues he was never meant to work with.

From then on, his fate was in his crewmate’s hands.

At 61 hours and 30 minutes into the mission, Lovell and Haise fired the lunar module’s engine to send them around the Moon, and then prepared for the main burn that would speed their way home.

Meanwhile, the Moon loomed into view.

“Well,” Lovell sighed. “I’m afraid this is going to be the last lunar mission for a long time.”

Despite their exhaustion, both crew and Mission Control worked through the mission with a calm focus, though the media painted a very different picture.

As camera crews camped out on the lawns of the astronaut’s homes, reporters painted Mission Control as a riot of chaos and fear, transforming every breath into a life-or-death struggle.

Lunar missions didn’t seem so boring now.

When the crew emerged from behind the Moon, they carried out their final burn. The lunar module’s engine was only designed for a single use, and no one knew how it would fare during this second firing.

To the crew’s relief, it lasted all four minutes and 24 seconds required.

The crew were finally heading home: splashdown would be in 3 days. They just needed to survive that long.

The most immediate concern was keeping the astronauts breathing. The lunar module’s oxygen reserves were more than enough for the crew, but when Odyssey shut down, so did its carbon dioxide filters.

Though Aquarius had its own, they were only meant to keep 2 people alive. Now they were supporting 3. The deficit would soon cause the gas to reach toxic levels.

Odyssey had spare filters – but they were square. The lunar module took round ones.

After a day of planning, engineers on the ground walked the astronauts through the process of making them fit using the assortment of items available onboard, and the crew could breathe easy again.

The next problem was water. Odyssey was cooled by the liquid but its tanks were meant to be topped off by the waste water produced by the now defunct fuel cells.

The crew limited their drinking to conserve as much as possible, eventually being rationed to just 200ml a day.

Elsewhere there was too much water, as the moisture in the astronauts’ breath and sweat built up in the air.

The heaters were set to a minimum to conserve power and the temperature was just 9ºC, meaning water condensed onto everything – including the crew.

Damp and cold, the astronauts took turns trying to sleep. While the one crewman on watch was taking pills to stay awake, the other two were shivering in their couches, unable to sleep.

There’s one whole side of that spacecraft missing. It’s really a mess.

Jim Lovell

Only Haise was having no problem staying warm. The combination of dehydration and exhaustion had led to a urinary tract infection and he was now running a fever.

Throughout the long trip home, the crew siphoned power from the lunar module to Odyssey’s batteries until it had enough power to operate the descent hardware the crew needed to survive splashdown.

Over 135 hours after leaving Earth, the crew were almost home again.

Only the command module could survive re-entry, so the crew jettisoned the service module which carried the problematic oxygen tanks.

As it floated away, Lovell pressed his face to the window to see what had happened.

“There’s one whole side of that spacecraft missing,” he said, seeing the tank had not just ruptured, but exploded. “It’s really a mess.”

The next vehicle was harder to say goodbye to – the lunar module which had been their salvation.

“Farewell, Aquarius,” said the voice of CAPCOM as it floated away, “And we thank you.”

As the crew prepared to land, millions of people on Earth gathered around televisions and radios, willing them a safe return while the news bandied fears that the heatshield had been damaged in the accident.

After running a marathon rescue, would Apollo 13 expire just yards from the finish line?

As the crew hit the atmosphere, the heatshield held. At 18:07 UT, 142 hours and 54 minutes after launching, Apollo 13 arrived home. Safe.

The recovery ship USS Iwo Jima rushed the crew to Honolulu where their families awaited. While they recovered from their ordeal, NASA hunted down the accident’s cause.

The culprit: a single switch meant to stop the oxygen tanks overheating had failed three weeks before the flight.

Temperatures in Tank 2 had risen to over 500ºC, damaging its wiring. When the crew stirred the tank it had sparked, igniting the oxygen.

One minor component in a machine made of millions had almost cost the Apollo 13 crew their lives.

But it was the work of many which brought those three lost souls home. While the press lauded the courage of the crew, the astronauts pointed out they’d never been alone – 100,000 people on the ground had helped them.

Apollo 13 mission brief

Launch date 11 April 1970

Launch locationLaunch Complex 39 A

Proposed landing locationFra Mauro crater

Duration5 days, 22 hours, 54 minutes

Return date 17 April 1970

Closest approach to the Moon254km

Firsts: aborted Apollo mission; use of lunar module as a lifeboat; furthest distance travelled from Earth (400,171 km)

Meet the astronauts

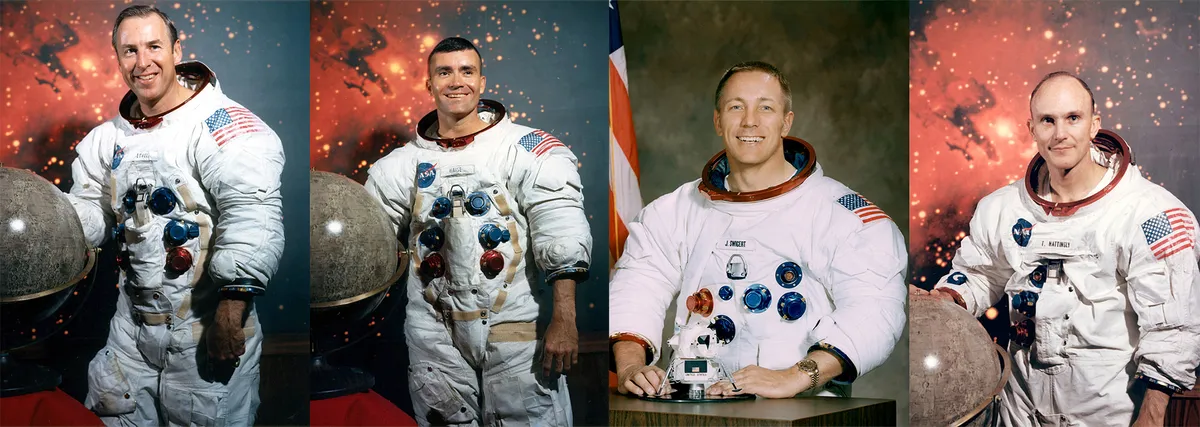

James ‘Jim’ Lovellwas a spaceflight veteran, having flown in Gemini 7, Gemini 12 and Apollo 8. During the latter, he trialled a method of navigation using Earth’s terminator which he used again during the Apollo 13 disaster. Like all the Apollo 13 crew, he never flew in space again.

Lunar module pilot: Fred Haise served in the Marines and the Air Force before joining NASA. He was meant to fly on Apollo 19 but this was later cancelled, and he moved into development of the new Space Shuttle. He went on to work for Grumman Aerospace Corporation, the company which built the lunar modules, including Aquarius.

Command module pilot: Jack Swigertwas in the Air Force and worked as a test pilot before joining NASA in 1966. He was one of the few astronauts who requested to be a command module pilot rather than walk on the Moon. He later entered politics and was elected to Congress but died before being sworn in.

Original command module pilot: Ken Mattingly was a former naval officer, who had been with NASA since 1966. During the Apollo 13 disaster, he ran simulations to help bring his crewmates home. He eventually reached the Moon with Apollo 16 in 1972 and flew two Shuttle missions. He still hasn’t contracted German measles.

Mission timeline

*All times are UT

11 April 19:13* Apollo 13 launches

14 April 03:06Tank 2 stirred, explodes a minute later

14 April 03:08“Houston, we’ve had a problem here”

14 April 04:37Mission Control and the crew consider Aquarius as a lifeboat

14 April 05:13Fred Haise shuts down last fuel cell – Moon landing now impossible

14 April 05:23Odyssey’s systems turned off to conserve power

14 April 08:42Mid-course correction nudges Apollo 13 into return trajectory

15 April 00:21Apollo 13 disappears behind the Moon, before emerging 25 minutes later

15 April 13:22 Crew fabricate a carbon dioxide filter

16 April 11:33 Power transfer to emergency batteries begins

17 April 13:14 Service module separates, and the crew photographs the damage

17 April 15:23 Odyssey is powered back up in preparation for the descent

17 April 18:07 Splashdown

Ezzy Pearson is BBC Sky at Night Magazine's news editor. This article originally appeared in the April 2020 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.