Mercury, the closest planet to the Sun and the smallest planet in the Solar System, is a desolate world.

The planet has almost no atmosphere, meaning there’s no protection from the Sun’s intense radiation.

The planet takes 59 Earth days to rotate once and 88 Earth days to orbit the Sun in an elliptical orbit.

It’s 176 days from one sunrise to the next, meaning the Sun bakes the surface of Mercury for months at a time.

With no active volcanism renewing the rock, the planet is covered in impact craters, leaving no doubt it's a dead world.

It’s the smallest of the major planets – even moons Ganymede and Titan are larger – but Mercury’s heart hides a heavy secret.

While most planets have a modest iron core at their centre, Mercury’s is thought to be enormous, spanning 85% of its radius.

Here are some facts about the planet Mercury.

It’s the closest planet to the Sun

Mercury orbits the Sun at an average distance of just 58 million kilometres (36 million miles), or ‘0.4 AU’, where 1 AU (astronomical unit) is the distance between the Sun and Earth.

It’s about 4.5 billion years old

While debate rages regarding the exact order in which they formed, all of the Solar System’s eight planets formed out of the Sun’s protoplanetary disk round about the same time, roughly 4.5 billion years ago.

It’s the smallest planet

According to NASA, Mercury has a radius of 2,440km (1,516 mi). This makes it a little over one-third the size of Earth (which has a radius of 6,378 km/3,963 mi), and the smallest planet in the Solar System.

It’s the lightest planet

Mercury has a mass of 3.3011×1023 kg – or, to put it another way, 0.055 the mass of Earth. When you consider that Jupiter is nearly 318 times Earth’s mass, you start to realise just how less massive Mercury is by comparison!

But it’s also the second most dense

Despite being the lightest planet in the Solar System, Mercury’s also the second densest, just behind Earth.

This is mostly due to the high iron content in Mercury’s core (more on which shortly).

It’s the fastest planet in the Solar System

The speed at which a planet orbits its parent star is a function of the masses of the two bodies, and the distance between them. As a result, planets closer to their stars have greater orbital velocities than those further out.

Here in the Solar System, far-flung Neptune has an orbital speed of just 5.43 km/s (12,146 mph) – but nippy little Mercury whizzes around the Sun nearly 10 times faster, at a staggering 47.87 km/s (107,082 mph).

It’s got the most eccentric orbit in the Solar System

None of the Solar System’s eight planets describes a perfect circle as they orbit the Sun.

But if they were in a competition to do so, then Mercury would be going home with the wooden spoon!

It has the most elliptical orbit in the Solar System, giving it an orbital eccentricity of 0.2056 (where a perfect circle would be 0.0000), compared to Earth’s 0.0167.

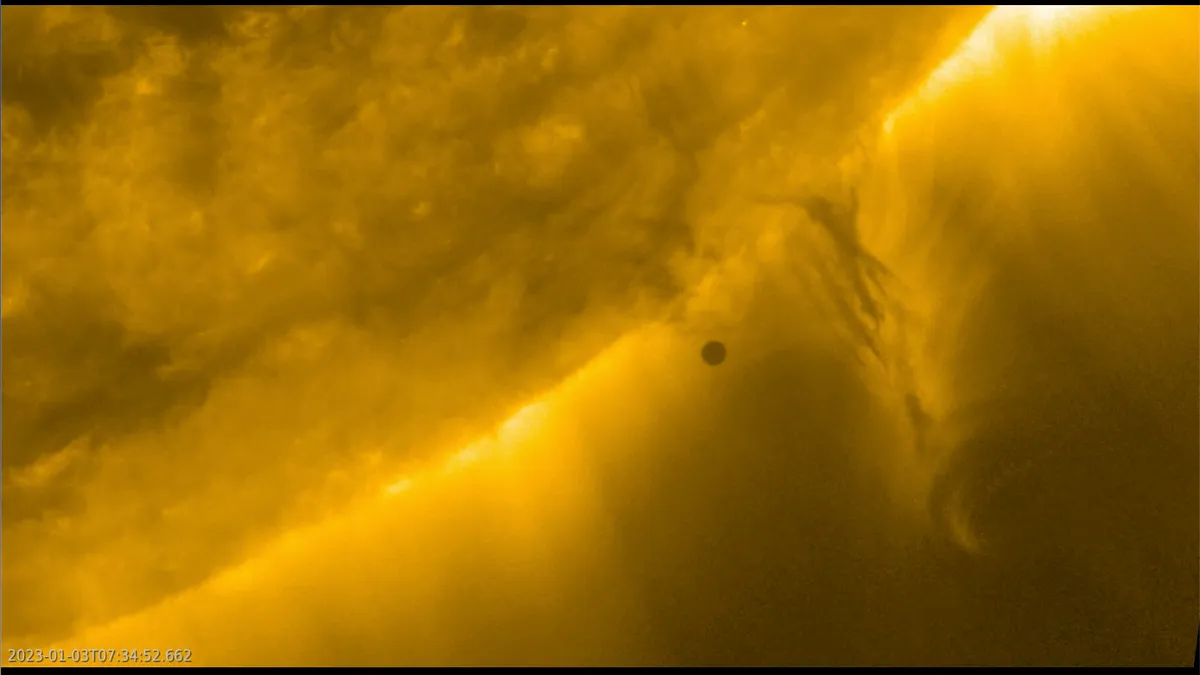

And the most tilted orbit

Solar System orbits are categorised by how much they deviate from the plane of Earth’s orbit (known as the ecliptic). Mercury’s orbit is tilted at 7° from the ecliptic, more than any other planet’s.

This, combined with its orbital eccentricity, makes transits of the Sun by Mercury (as seen from Earth) quite rare, occurring only about once every seven years.

It has no seasons

Mercury might have an eccentric, slanting orbit but at least it can sit up straight!

It has the least axial tilt of any Solar System planet, at just 0.01° compared to Earth’s 23.4°.

As a result, Mercury doesn’t experience Earth-like seasons.

It does, however, have ‘thermal seasons’ resulting from its odd orbit – the further it is from the Sun, the cooler it gets.

It’s only the second warmest planet

Mercury’s eccentric orbit means that although it’s technically the closest planet to the Sun, it spends a lot of its time much further away, and hence absorbs less solar energy.

Neighbouring Venus, with its more regular orbit, spends more of its time basking in sunlight and so claims the temperature gold.

It has no moons or rings

Mercury’s a bit too small and too close to the Sun to have hangers-on.

Any dust particles or small lumps of rock in its immediate vicinity would be sucked in by the Sun’s gravity rather than going into orbit around the tiny planet.

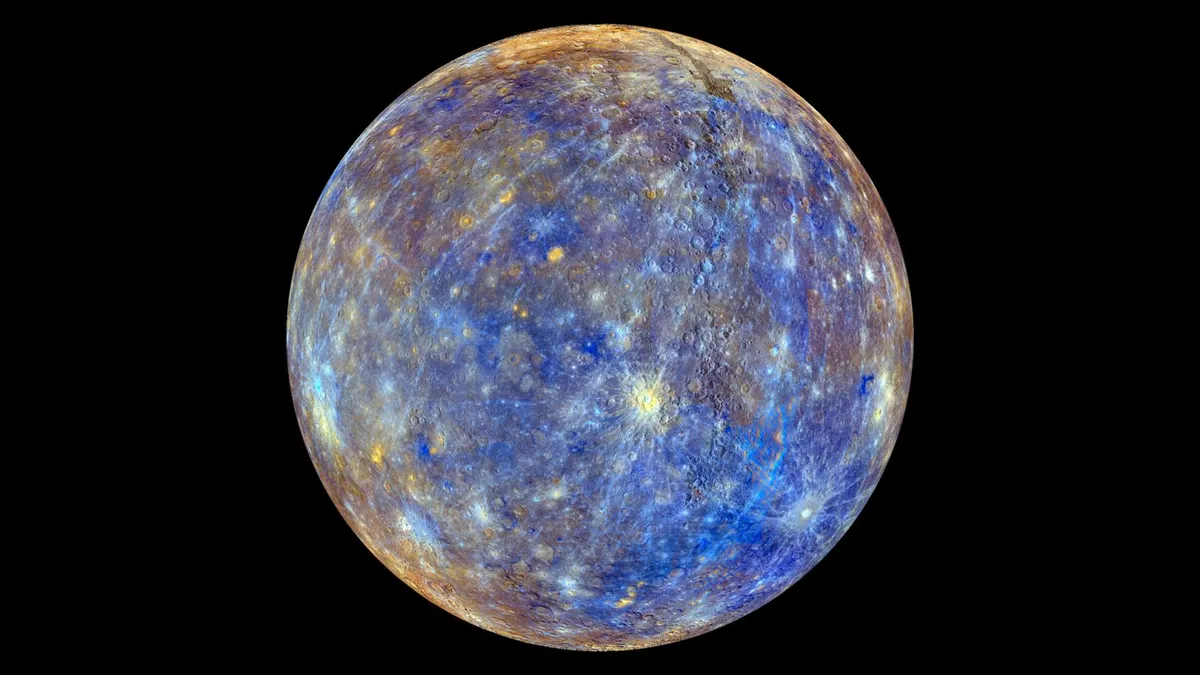

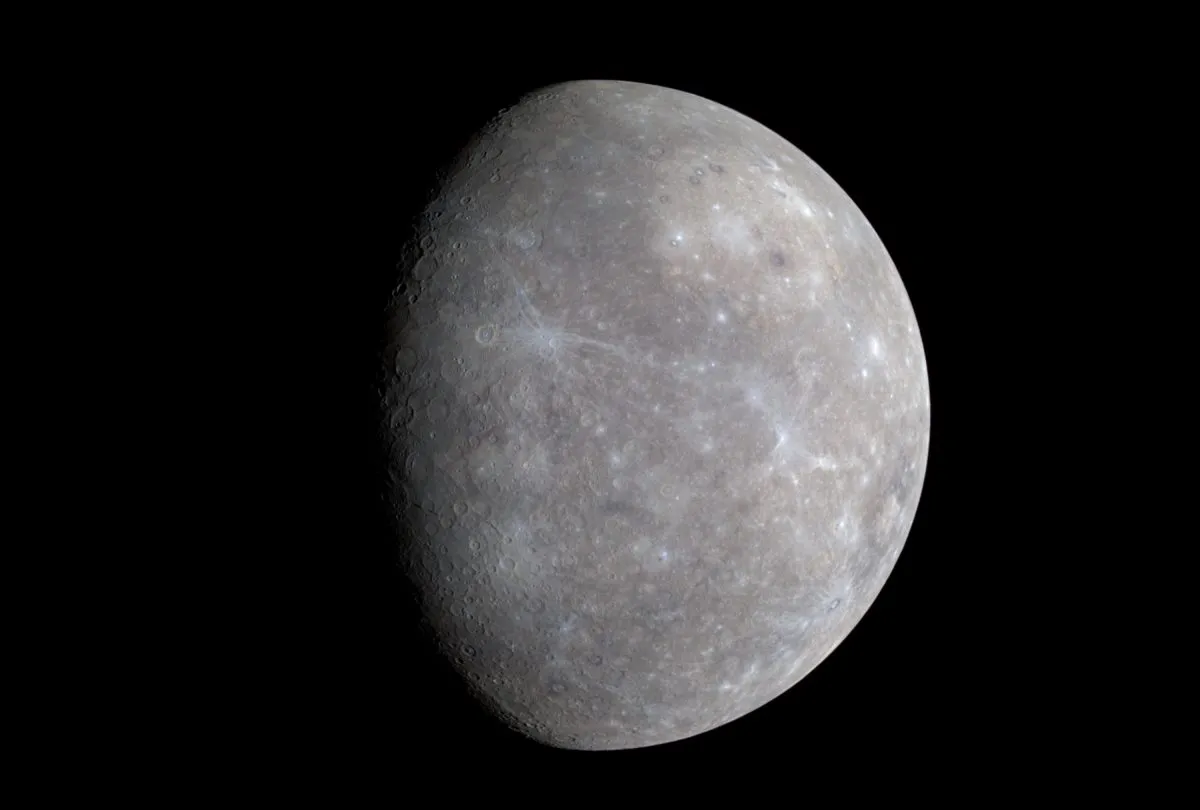

Mercury's surface looks much like the Moon

Mercury’s surface would appear greyish-brown if you were standing on it, and just like the surface of our own Moon, it has areas that are very flat and areas that are heavily cratered.

This is a result of both bodies being geologically inactive, with very little going on in the way of plate tectonics or volcanism.

It’s named after the Roman god of communication

To the ancient Romans, Mercury was both the god of communications and the messenger of the Gods – hence why his name was given to the fastest-moving planet in the Solar System.

The Babylonians called it Nabu

The Romans weren’t the first to associate speedy Mercury with fleet-of-foot deities.

The ancient Greeks called the planet Hermes (essentially Mercury’s equivalent among the pantheon of Greek gods) while the Babylonians called it Nabu, who again was the 'messenger of the gods' according to their belief system.

It’s been associated with owls, water and Wednesdays

The Mayans used an owl as the symbol for Mercury, while the ancient Chinese knew it as the 'Hour Star' and linked it to both water and the direction north.

And somewhat oddly, Mercury is associated with Wednesdays both in Germanic paganism and in Hindu mythology.

Its apparent magnitude (brightness) varies considerably

Due to its highly eccentric orbit, Mercury’s distance from Earth fluctuates considerably and so, therefore, does its brightness.

Its apparent magnitude can range from -2.48 (brighter than Sirius, the brightest star in the sky) to +7.25 (invisible to the naked eye)

It can only be seen at twilight

Glare from the Sun makes tiny little Mercury extremely hard to spot. It’s only really visible from Earth during morning and evening twilight.

By day there’s too much sunlight, and at night you’re facing in the wrong direction.

Hubble can’t see Mercury

The Hubble Space Telescope has safety mechanisms that prevent it from turning its gaze towards the Sun, to avoid damaging the sensitive optical equipment onboard.

As Mercury’s so close to the Sun, that rules out Hubble studying Mercury, too.

It’s more visible from the Southern Hemisphere

Observers south of the equator are better served than their northern counterparts when it comes to seeing Mercury.

The planet reaches its maximum western and eastern elongations in the Southern Hemisphere’s early autumn and late winter.

At these times, as seen from places like South Africa, Argentina and Australia, it rises a few hours before dawn and doesn’t set until a few hours after sunset, respectively – giving observers a few hours’ viewing window.

Its days and years are seriously weird

Mercury takes 88 Earth days to travel around the Sun and 59 Earth days to rotate on its axis, making a ‘year’ and a ‘day’ on Mercury 88 and 59 Earth days, respectively.

However, due to its eccentric, tilted orbit, each Mercurian hemisphere experiences a full year (88 days) of complete darkness, followed by a full year (88 days) of constant sunlight.

So a ‘solar day’ on Mercury (the time from one sunrise to the next) actually lasts for 176 days, or two Mercurian years!

The Sun does strange things in Mercury's sky

Were you able to stand on the surface of Mercury, then depending where you are on the planet, you may see the Sun rise, get about two-thirds of the way across the the sky and then reverse, setting where it rose before rising and setting (in the normal way) again. All in a single day.

It has a very weak magnetic field

Mercury’s magnetic field has just 1% of the strength of Earth’s.

That’s still enough to deflect the solar wind, so it does have a magnetosphere of sorts.

And this magnetosphere can trap plasma from the Sun and spend it spiralling down to the surface, where the hot particles contribute to space weathering.

It has virtually no atmosphere

Between the Sun’s enormous gravity and Mercury’s low gravity and magnetism, there’s not a lot keeping gas particles close to the surface, so Mercury has no atmosphere to speak of.

It does, however, have a faint exosphere: a far less-dense and non-permanent conglomeration of hydrogen, helium, oxygen, sodium, calcium, potassium, magnesium, silicon and hydroxide.

In this respect, it’s more akin to large natural satellites and dwarf planets, like the Moon, Jupiter's moon Ganymede or dwarf planet Ceres, than it is to the other rocky planets.

It experiences a huge range of temperatures

A combination of its eccentric orbit, its lack of an atmosphere, tidal effects resulting from its proximity to the Sun and its unusual 3:2 spin-orbit resonance (the ratio of its orbital and rotational periods) results in enormous temperature fluctuations at Mercury’s surface.

At the equator, temperatures can reach 430°C (800°F) by day, and then plummet to -180°C (-290°F) at night.

There’s probably water ice at the poles

Most of Mercury gets too hot for water to exist on its surface, but the floors of some deep craters towards the poles are in permanent darkness.

Temperatures there never reach higher than -171°C (-276°F). And the presence of water ice is thought to be the most likely explanation for the patches of high radar reflectivity that we see in these regions.

There’s water vapour in the exosphere

Mercury’s exosphere contains some water vapour.

The hydrogen and oxygen atoms involved may have been propelled upwards from the surface by (eg) comet impacts, or (in the case of hydrogen) been delivered by the solar wind.

It used to be more volcanic than it is

Thought the planet is geologically inactive now, it did have volcanoes once.

We know this because the surface shows evidence of pyroclastic flows, the kind you would expect to see around low-profile shield volcanoes.

It once had a magma ocean on its surface

Mercury’s very homogenous mantle and regions of flat, sweeping plains suggest it probably had a magma ocean at some point in its history. Again, much like our own Moon.

Its surface is covered in ridges

Some areas of Mercury’s surface are scarred by ‘wrinkle ridges’, AKA dorsa.

When the planet began to cool, soon after forming, it contracted – causing ridges to appear on the surface.

The largest of these ridges can be up to 1,000km (620 mi) long and 3km (1.9 mi) tall. Dorsa are also seen on the Moon and Mars.

Its inner structure may have an extra layer

Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars all have a core, a mantle and a crust.

But many geologists believe Mercury has an additional layer called an anticrust – a solid layer sitting between the molten rock of the mantle, and the liquid metal of the outer core.

However, not all geologists agree that this is the case.

Its core is very iron-rich

Mercury’s core has a higher percentage of iron than any other planetary core in the Solar System.

This is thought to be the result of one of two things.

Either there was once a giant impact that blasted most of Mercury’s crust and mantle out into space (making iron in the core a much larger proportion of the planet’s overall volume).

Or the planet formed a little earlier than the others, when the Sun was hotter, with the result that much of its original rock was vapourised by the extreme temperatures.

Its mantle and crust are just 420km deep

Put together, Mercury’s mantle and crust extend just 420km (260 mi) below the surface.

Earth’s mantle and crust, in comparison, reach a depth of 2,900km (1,000 mi).

The crust itself is fairly similar to Earth’s: it’s around 25-35km (15-22 mi) thick, where Earth’s crust is about 25-70km (15-45 mi) thick on land, and 5-10km (3-6 mi) thick on the ocean floor.

Its most visible surface feature is ‘the spider’

There’s a great ridged plain on Mercury’s surface called the Pantheon Fossae, at the heart of which sits a 40km (25 mi) crater.

Today, this crater is called Apollodorus (after the Roman architect behind the Pantheon) but it was traditionally called ‘the spider’, due to the large, bright ridges that appear to radiate outwards from it.

However, this crater may not actually have caused the ridges. Some scientists think it’s a more recent phenomenon caused by a later impact.

Its largest crater is Caloris Planitia

The largest impact feature on Mercury is a depression called the Caloris Planitia.

Though with a diameter of around 1,550km (960 mi) this is classed as an impact basin, not a crater (impact basins are craters with a diameter of more than 300km).

Which explains the name, because…

There are strict protocols for naming its features

As with other bodies, features on Mercury are named according to rules laid down by the International Astronomy Union.

Craters are named after artists, musicians and writers.

Dorsa are named after scientists whose work has improved our knowledge of the planet.

Plains are named after the word for Mercury in different languages.

Depressions are named after works of architecture, valleys after abandoned ancient cities and escarpments after famous ships.

It's one of the ‘classical’ planets

That’s another way of saying that, because Mercury is a naked-eye object at least some of the time, we’ve known about it pretty much forever.

The first known written mention is on the MUL.APIN tablets.

Carved in clay, these are essentially a star catalogue compiled by the ancient Babylonians between 700 and 1400 BC.

It was first observed through a telescope in around 1610

At this point you’ll be thinking ‘Ha, I bet that was Galileo!’ – but you’re only half right.

Galileo and English astronomer Thomas Harriot (another, less-feted telescope pioneer) both reported seeing Mercury about the same time, and no one can say for sure who was first.

The first spacecraft to visit was Mariner 10

Mariner 10 launched from Cape Canaveral on 3 November 1973. It conducted its first flyby of Mercury on 29 March 1974, coming to within 703km (437 mi) of the surface.

Two further flybys came in September 1974 and March 1975, the last within 327km (203 mi) of the planet’s north pole.

Mariner 10 provided our first close-up images of Mercury, but was shut down remotely by NASA after its last flyby.

It’s believed to still be up there, orbiting the Sun, even now.

The next, and so far last, was MESSENGER

Mercury’s next visitor was the MESSENGER (MErcury Surface, Space ENvironment, GEochemistry, and Ranging) probe.

MESSENGER launched in 2004, reached Mercury in 2008 and completed three flybys before inserting itself into orbit in 2011.

It stayed there until it was deorbited by NASA in 2015, crashing into the surface on 30 April that year.

ESA/JAXA mission BepeColombo is on its way there now

A joint project between the European and Japanese space agencies, BepiColombo consists of two satellites – ESA’s Mercury Planetary Orbiter (MPO) and JAXA’s Mio (AKA the Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter, MMO) – linked to a propulsion module, the ESA-built Mercury Transfer Module (MTM).

BepiColombo launched on 20 October 2018 and is due to arrive at Mercury in November 2026.

Getting there isn’t easy

Due to the close proximity and enormous gravity of the Sun, any spaceship manoeuvres in the region are incredibly energy-intensive.

It takes more fuel to reach Mercury than it would to leave the Solar System entirely!

But that’s okay: it’s not like you’ll ever be planning a holiday there, because sadly…

The chances of it hosting life are basically zero

With extreme temperatures, no atmosphere and constant bombardment by solar radiation, conditions on Mercury are so extreme, life could never exist there.

At least, not in any form that we would recognise.

Did we leave out any Mercury facts? What are your favourites? Let us know by emailing contactus@skyatnightmagazine.com