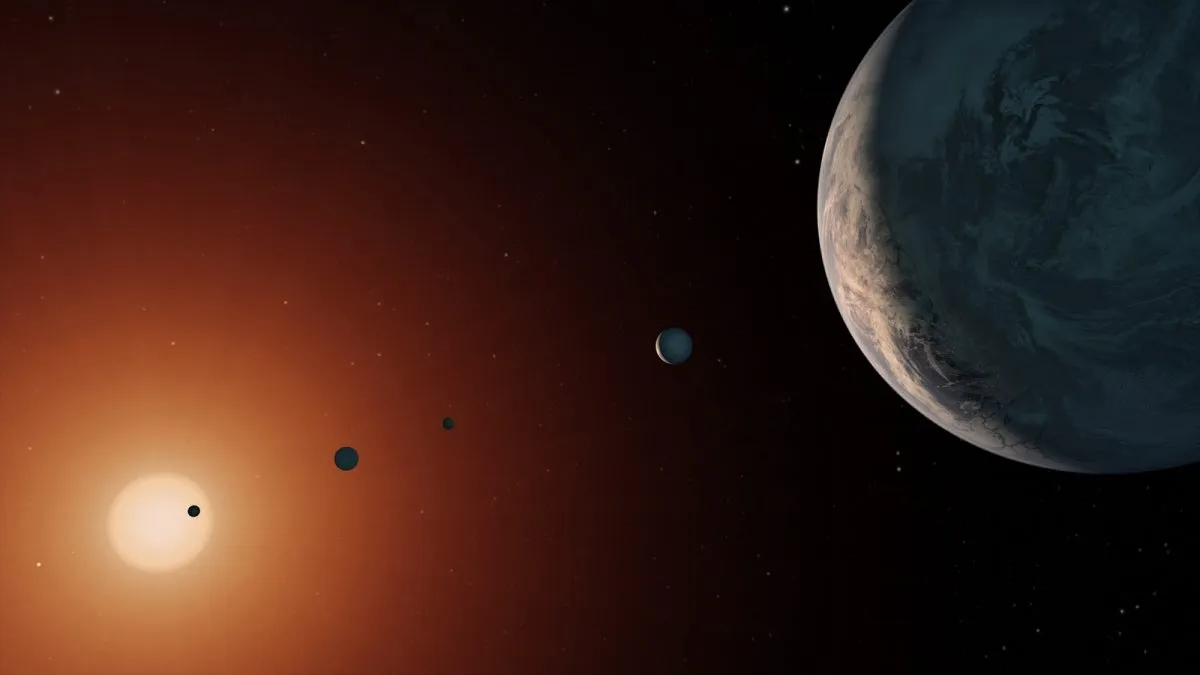

We had yet to find an exoplanet when Hubble launched, but 30 years later the telescope is helping to reveal the atmospheres of these distant worlds.

We spoke to astrophysicist Dr Hannah Wakeford about her work using the famous telescope to characterise planets orbiting stars beyond our Solar System.

Why do we study exoplanet atmospheres?

We don’t have an idea what a planetary system should look like. If you look at the Solar System you see four small planets and then four giant planets. Is that normal?

Venus is almost the same mass and radius as Earth. Remove that from our Solar System and we would assume that an exoplanet that was the mass and radius of Earth must be like Earth.But we have an example in our Solar System where that’s not the case.

Exoplanets enable us to take what we know from our Solar System and turn it on its head. What happened to make these ‘hot Jupiters’ that didn’t happen in our Solar System?

How is Hubble used to explore the atmospheres of exoplanets?

We use Hubble to look at exoplanets while they pass in front of their star. If the planet has an atmosphere, some of the star’s light will shine through it before reaching our telescope.

That light will change as different colours are absorbed depending on what makes up the atmosphere. We’re able to measure the way the planet’s atmosphere blocks the star’s light and work out what’s in it.

Why do you use Hubble?

We use the Hubble Space Telescope because we are sitting inside an atmosphere. If you want to look for things such as water vapour, then our own atmosphere is also filled with water vapour and that gets in the way.

Hubble sits outside the atmosphere, which means we don’t have to worry about the gases in the air getting in the way.

What are you looking for in an exoplanet’s atmosphere?

It’s different depending on what type of planet we are looking at. Many of the planets we’ve been studying in detail are these Jupiter-sized worlds that are very close to their stars, ‘hot Jupiters’. Here we’re looking for hot water vapour.

For smaller worlds, those roughly the size of Neptune or smaller, we’re still looking for water vapour, but we’re determining whether they are planets like Earth and Venus or if they’re more like Jupiter.

How do you choose which planets will get studied with Hubble?

It can be based on a particular question that we want answered. But honestly, it’s whichever ones we can get a good signal for.

There are thousands of worlds that have been discovered, but there’s only a few hundred of these that we can observe easily with our telescope.

These are really difficult measurements to make but we will observe it again and again if we have to until we can get that signal.

What have you learned so far?

That nature has a better imagination than we do. There is a huge number and diversity of planets out there. These exoplanets are all different from each other and their environment has a huge impact on what the nature of these worlds is.

One of the exciting things that we’ve discovered is clouds. Earth’s clouds have a huge property in reflecting light away but also keeping heat in.

Some of these exoplanet atmospheres are so hot, they’re so close to their star, the clouds we expect to form there are not liquid drops of water, but tiny pieces of rock suspended in the atmosphere.

It’s exciting because these clouds are made of glass, rubies, sapphires – gems that we find on Earth.

How long will Hubble continue observing exoplanets?

Hubble is going to be working for us for the next 5 years at least. It’s a fantastic instrument, but it’s also limited.

In the future we’re going to get the James Webb Space Telescope, launching in 2021. It will have a much larger 6.5m telescope.

We’ll be able to measure exoplanets in more detail and look at the water vapour in the atmosphere, alongside the carbon dioxide, methane or carbon monoxide that we haven’t been able to measure.

Combining what we’re learning right now with what we measure in the future is going to be important for evolving the field of exoplanet research.

Dr Hannah Wakeford is an astrophysics lecturer at the University of Bristol. Keep up with Dr Wakeford's research via her Twitter account, and find out more about her research via the University of Bristol's website.

This interview originally appeared in the May 2020 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.