Professor Brian Cox returns to BBC 2 with his new TV series The Planets, looking at the origins of our Solar System and exploring the latest discoveries made by space-faring probes.

BBC Sky at Night Magazine spoke to Professor Cox to find out more about the new series and his thoughts on the future of space exploration.

What new insights into the Solar System can viewers expect from The Planets?

What’s been remarkable over the past decade or so is the amount of detail we’ve been able to put into the story of the Solar System.

And this has mainly been driven by planetary exploration missions.

In 2009 when we were making Wonders of the Solar System, the Cassini probe had only just arrived at Saturn.

In this new series, in the Jupiter episode we explore the Grand Tack model, whereby Jupiter migrated inwards in the early Solar System, but was then pulled back out by the gravitational pull of Saturn.

It seems very fantastical, but is a very recent development based on observations by space probes and an increasing sophistication in computer modelling.

What’s also critical for our understanding of the Solar System is the fact that we’ve now seen well over 3,000 exoplanets around distant stars.

What we’ve seen is the geography, the layout of other systems is not like our own.

One mission that is incredibly exciting from a scientific perspective is Juno, which is providing these magnificent, very strange images of Jupiter, for example showing the planet’s poles with its different colours and swirling clouds.

Juno has not really had an impact yet on our picture of the development of Jupiter in the Solar System, because the data is only just coming back.

Its aim is really to take a cross-section of Jupiter; like a 3D description of Jupiter that will allow us to understand more about how it formed.

Mercury almost certainly formed further away from the Sun, and this is a very new idea, based on a spacecraft that went there and observed the chemical composition of the surface.

There’s an underlying philosophy to the series, that the Solar System is a ‘system’.

I think it’s quite natural for us to focus our eyes on Earth alone and to think that we’re isolated from the goings on in the rest of the Universe.

This is not the case. There are some very practical reasons why we need to pay attention.

One example is of course asteroid strikes, which are not beyond our reach by any stretch of the imagination; we will be hit by them again.

But I also think that over the years, space exploration has taught us a lot about ourselves, and our own planet.

Understanding the way Mars and Venus have evolved, for example, we see that atmospheres of planets can change.

This is what happened to Venus. We see a planet that was probably Earth-like, but is now the hottest place in the Solar System and is often described as a vision of hell, because of the way that its atmosphere changed.

We see the greenhouse effect in action. These observations of the Solar System are important beyond the science.

They’re not just interesting, they actually teach us that we as a species are very fortunate indeed, and actually in a rather precarious position.

Was there anything new that blew your mind while filming The Planets?

Absolutely. The Grand Tack is one of them. We see that the evolution of Solar Systems is extremely complicated.

Mercury almost certainly formed further away from the Sun, and this is a very new idea based on a spacecraft that went there and observed the chemical composition of the surface.

It discovered elements like sulphur and phosphorous, which were not present close to the Sun when the planets were formed; they only exist in large quantities further out in the Solar System.

When you begin to piece together observations like that with computer modelling, it tells you that our Solar System is significantly more dynamic than we’d thought.

The geometry of the Solar System that we see today was not the same when it first formed.

I think we tend to think of our Solar System as a sort of fossilised remnant; that the structure of the initial cloud around the Sun 4.6 billion years ago is echoed in the distribution of the planets.

What we’ve learned recently, and this was quite surprising to me, is that is not the case.

The Solar System was very dynamic and planets were moving around in the early years. There are so many aspects that feed in to the reasons why our planet is the way it is today.

What do you hope people will take from The Planets?

Films about the Solar System are ultimately films about us; about Earth. I think people feel detached from nature, and that would be a mistake.

Science is an attempt to understand nature, of which we are a part. That’s vital for our survival.

One very legitimate question we can ask is ‘how do planetary atmospheres evolve?’.

We’ve found that planetary atmospheres are rather fragile things, and they can evolve in response to small changes.

We’ve seen that not only by measuring Earth’s atmosphere, but also trying to model Venus’s atmosphere in particular, and also Mars’s atmosphere and how it lost its atmosphere.

Investigating the Solar System allows us to test our understanding of Earth.

What’s next for planetary exploration?

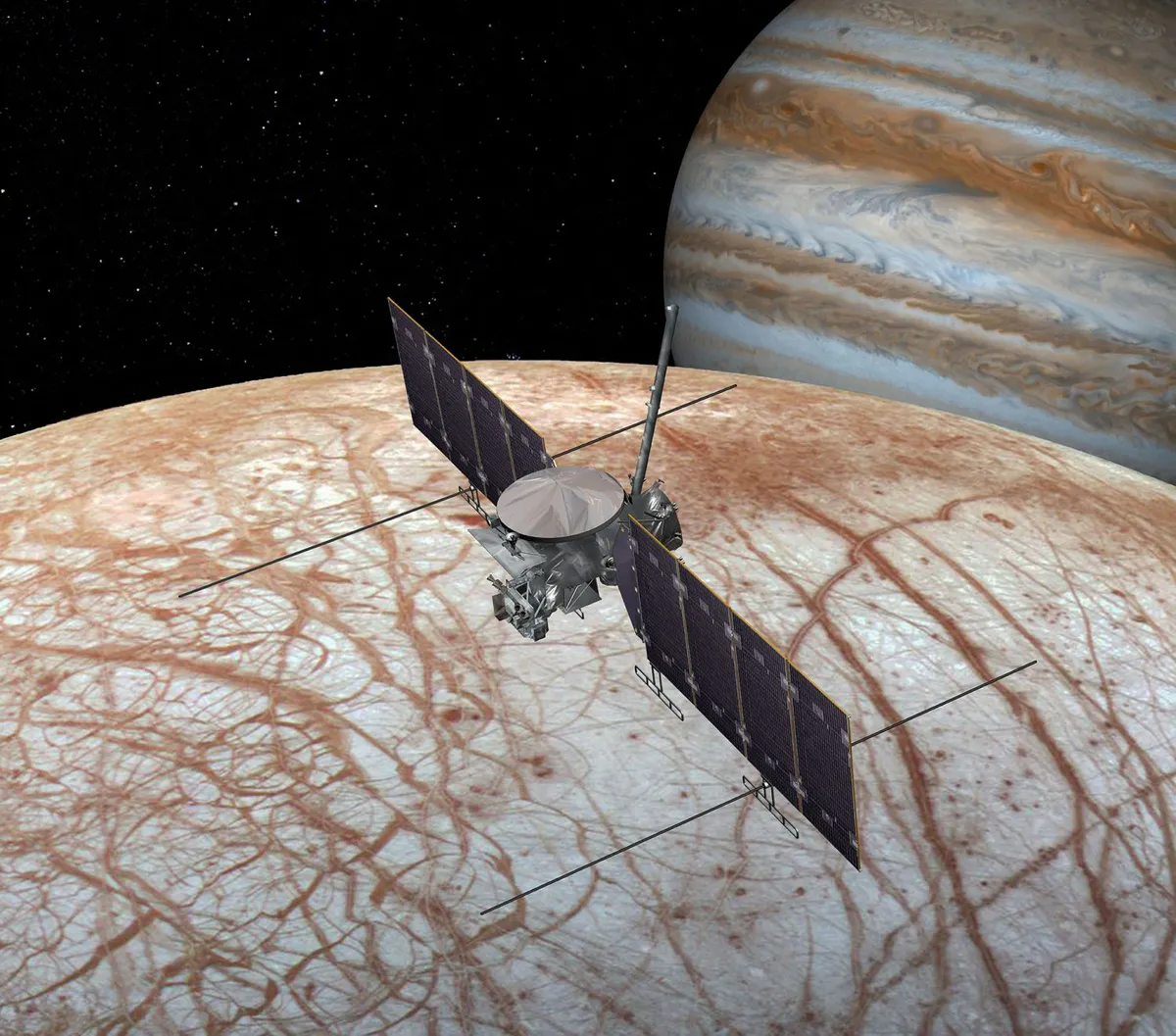

The next big mission for NASA is the Europa Clipper, which is a Jupiter orbiter but is focused on its icy moon Europa.

Some of the biggest questions at the moment are in astrobiology, which we deal with in some of the episodes in this new series.

That question: “is there life?” particularly on Mars and/or some of the icy moons in the Solar System, is at the forefront.

And that’s what the Europa Clipper mission is designed to look at.

It’s also designed to scope out landing sites on Europa to try and understand whether it might be possible to get a spacecraft into its subsurface ocean.

When you speak to the planetary science community, if you think about the outer Solar System, yes we’ve completed the initial reconnaissance, but we’ve only been at these planets for a few hours.

Uranus and Neptune, plus Pluto; we’ve just flown straight past.Then consider the incredible, detailed analysis of Jupiter and Saturn that we’ve seen.

For example we’re now beginning to suspect that the rings of Saturn might be extremely young.

This is a very recent discovery, partly driven by the final few orbits Cassini made, when it performed its dives in between the rings and the planet.

That allowed us to characterise the mass of the rings and begin to understand their evolution.

They may be only tens of millions of years old. So it’s a question of detail; getting orbiters out to the outer planets.

One of the next big missions would be to Saturn’s largest moon Titan.

In one episode we focus on Titan, which is a planetary-sized moon with a very thick atmosphere.

It has a liquid water ocean below the surface, and has the most complex organic chemistry of any body in the Solar System other than Earth.

There’s a plan to put what is essentially a helicopter drone onto Titan, and the gravity is a ninth of Earth’s gravity, and its atmosphere is denser than Earth’s.

So I think that astrobiology is going to be the focus of the next two big NASA missions.

Beyond that I’d like to see orbiters around Neptune, in particular.

I think there’s a lot of pressure to put an orbiter around the outermost planet, but it’s very difficult to do.

How do you decide what to focus on in each episode?

When you make a series about the planets, there’s a temptation to make each episode about a planet, but then of course you’d have to make eight; nine if you want to include Pluto.

So you end up with themes, and in the Jupiter episode we put across the theme that we live in a system.

The episode is about Jupiter, but also about the system. Some of the other episodes in the series are very much focussed on the planets themselves.

The gas giants are particularly interesting because of their moons. Saturn’s moon Enceladus is an interesting world.

This is a small icy moon of Saturn with activity. It’s got liquid water below its surface; almost certainly hydrothermal vent systems on the floors of its oceans, and so the chemistry that we think might have led to the origin of life on Earth is present on that moon today.

Do you think there are any ethical questions with colonising Mars and potentially contaminating it?

If there are microbes on Mars, we do not want to contaminate it with Earth microbes.

There’s a scientific reason for that, which is that if there is life there we’d like to see whether there was a second genesis, or whether there was just one genesis on Earth or Mars.

We know that organic material can be transferred between planets. So contaminating Mars would ruin the science.

In terms of the ethics, the question is ‘how important are microbes?’ They’re important scientifically of course.

But there’s also the argument that intelligent civilisations are likely extremely rare and valuable, and cannot survive for long on a single planet.

The Solar System was very dynamic and planets were moving around in the early years. There are so many aspects that feed in to the reasons why our planet is the way it is today.

There’s a philosophical trend that has been there since about the 1950s I think, or even before; the idea that we as a species need to see ourselves as a spacefaring species that has access to resources beyond Earth.

I think that we have to be very careful from a scientific perspective about damaging potential ecosystems on Mars, and we are very careful.

We take it very seriously. But at the same time, I don’t think this can stop us from going to Mars.

It is the only place we can go beyond Earth. In any plausible scenario, there is nowhere else that humans can go to begin their steps outwards from Earth, other than Mars and the Moon.

There may or may not be Martians, and we need to find out, but there will be Martians if we are to have a future. At some point, we will be the Martians.

We can’t stay on Earth forever. The great challenge on Earth at the moment is to manage an expanding population that is confined to a very small planet, putting a lot of pressure on the resources that are here.

The Planets is currently screening on BBC 2. For dates and times, or to catch up with previous episodes, visit the programme's official website.