Ever wondered how the special effects and graphics on BBC Two's The Planets documentary series were produced? The series, which is hosted by Professor Brian Cox, contained over 2.5 hours of CG graphics, which is around the same as a feature length film.

We spoke to Andrew Cohen, Head of the BBC Science Unit and executive producer of The Planets, and Rob Harvey, Creative Director at Lola Productions, to uncover the secrets behind The Planets.

The cost of producing such material is high so the production company must come up with novel and creative ways to create such content.

We investigated how The Planets' special effects have set this documentary series apart from the rest and how they've brought a new dramatic twist to the tales of our planetary neighbours.

Andrew Cohen Q&A

Andrew Cohen is Head of the BBC Science Unit and Executive Producer of The Planet

How has this series differed from other documentaries you have produced?

Having spent 25 years at the BBC Science Unit, you carry its heritage and history with you, constantly looking forward. Planet related documentaries happen every ten years at the BBC and therefore we knew we had to produce something different, something that would stand out.

How did you make sure this was something different?

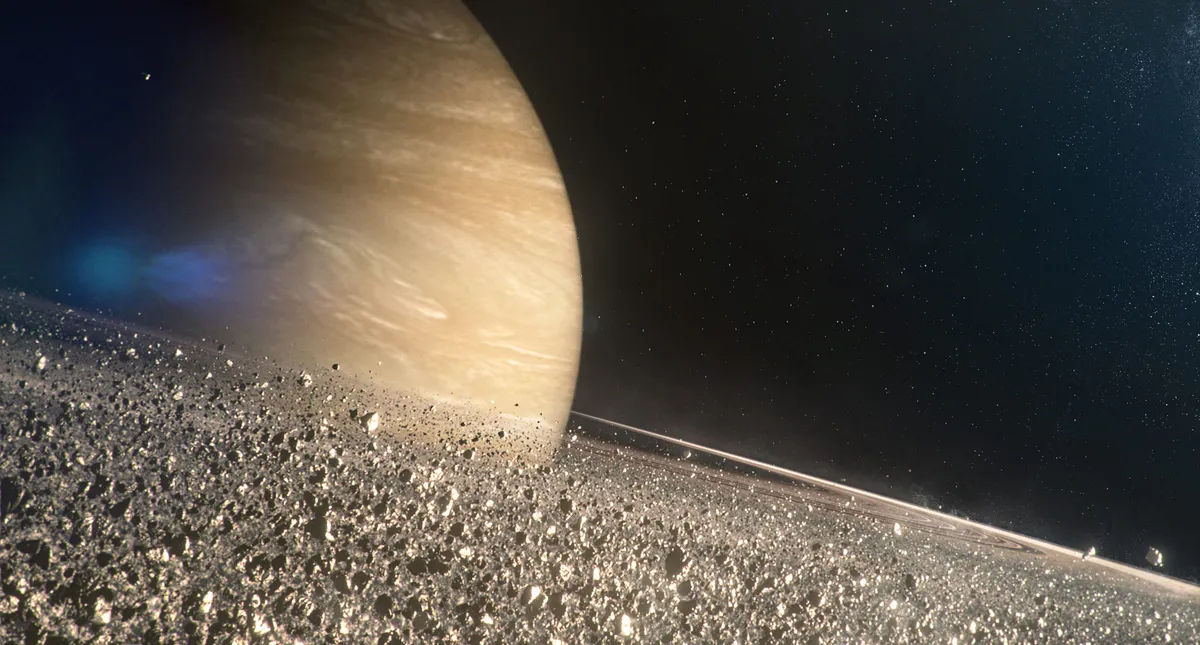

Nobody had told the story of our Solar System, the story of the planets’ 4.5-billion-year history. We knew then we had the opportunity to produce something different; a drama of planetary proportions.

The marriage of contemporary science with extraordinary drama; we wanted to create an immersive story rather than a lecture. Novel graphics were therefore needed to be able to tell the stories and bring the planets to life.

Have you faced any new challenges with this series?

One of the biggest challenges we faced was having the story told through the graphics. Normally graphics are supportive, rather than the primary storytelling device.

We had to think of the graphics as stories in themselves. All of this meant we needed to carry out a huge amount of scientific research in conjunction with the Open University in order to turn the graphics into beautiful sequences

How did you research the science behind the graphics? How scientifically accurate are they?

First and foremost, we had to locate a production company that would take on science validity as a challenge rather than run away from it. Lola Post Production were just the team to be able to drive the science into the graphics.

Throughout the series we worked closely with a large group of academics, many of whom are shown at the end of each episode. Working in partnership with the Open University meant there was a wealth of knowledge easily accessible to us.

The scientists did a good job of reigning us in if they thought the production side of things was making a particular scene too dramatic, with the science not really standing up.

We always made sure we had multiple scientists prodding the script in order to keep it in the realm of believability and factual understanding.

Where there any scenes you couldn’t include because the science didn’t ‘stand up’?

A lot of the science we were communicating in The Planets was cutting edge.

A story that we had extensive talks about but decided not to include was that the late heavy bombardment of Mars resulted in the turning off of the Martian magnetosphere.

This is thought to have effectively caused Mars to die. Though this would have made a brilliant story, it couldn’t stand up to the scientific rigor.

This is a novel research area and although there is some science in that direction, we couldn’t push it too far as it is not watertight.

What was your inspiration behind the iconic opening sequence?

Inspiration can come from the most unlikely of places. I was watching Coco, the Pixar film, and when I saw the opening scene it really caught my imagination.

Wanting to avoid stereotypical ways to open a documentary we sought to show the audience from the start that this was not a typical documentary, it was an immersive drama.

Rob Harvey Q&A

Rob Harvey, VHX Supervisor, The Planets. Lola Post Production

How easy was it to work with scientists when producing the graphics?

It all worked really well. We had the Open University sitting in the background with the BBC acting as a barrier, getting the feedback from the scientists and then relaying it back to the graphics team.

This way the feedback was slightly filtered and didn’t tread all over the creative aspect of the show.

Was the end product well received by the scientists involved?

The feedback was all really positive; they liked how their research was conveyed.

A lot of the time they are looking at dry graphs and blurry images, so when they see it brought into focus and sharp they get really excited.

I wasn’t sure where real life ended and graphics began, was this deliberate?

Yes. We wanted to blur the lines between real images and graphics in order to keep you in the moment.

Were all the graphics computer generated?

No, not all. Due to the high cost in both computer power and money, a lot of the graphics were filmed with a camera rather than computer generated.

We would take a scene, then pick an element of the scene that captures what we are trying to convey, then we simply went to the studio and experimented.

Filming different elements then layering them all up is like painting with film, gradually making an image.

Can you give us some examples?

Take Venus. The scene of the liquid hitting the hot surface of Venus was actually liquid nitrogen hitting a camping hot plate in slow motion.

This scene was actually just cut straight into the programme raw.

Another example are the giant electrical storms we pass through as we head down to Saturn’s core.

These are produced with liquid nitrogen and single use flashbulbs.

Did you have any kickbacks during production?

We had very few. Mainly the kickbacks came from producing the scenes for the terrestrial planets.

We had issues with some of the landscapes on Earth not quite matching the planets they were supposed to be in terms of layout of the land.

This involved chopping off a few mountains for example, to make the scene more accurate.

Where there any particularly tricky scenes? Any that took longer to produce than you originally thought?

Mars was the trickiest episode. It was the first one we produced and we were still finding our feet.

We also had some big pieces in that episode: the late heavy bombardment, Curiosity rover on the surface and the Martian waterfalls.

Which was easier to interpret and produce, terrestrial planets or the gas and ice giants?Each has their own problems to overcome.

When we were shooting scenes in Lanzarote for Mercury, it was a very foggy day.

Mercury has no atmosphere, so to match the location to the planet we had to strip off all the fog when editing the footage.

The storms on Saturn and Jupiter were tricky to get right with regards to scale.

We had to create footage for these as using computer graphics would have taken weeks to simulate the conditions.

Was there anything you wanted to include but you couldn’t?

No not really. We did have some ground rules laid out from the start as we wanted everything to appear believable and to scale.

We didn’t allow the camera to travel at ridiculous speeds, so there are no shots of the camera flying around the planet and through the middle in 3 seconds.

This would take you out of the cinematic story, it would become more about the graphics and less about the effects and stories.

You wanted to avoid making the graphics too much like a ‘textbook documentary’. Is that why Brian explains a lot of the science in person?

Yes! For example, we have Brian explaining the migration of planets with pebbles and stones.

It's a much more engaging way to explain what is happening.

You don’t need to see it with big graphics, you just need it explained in a way you can understand. Showing it with graphics, you will never appreciate the scale.

Talking about scale, how do you manage to get this across?

When you present large scale things quickly they look small.

We wanted everything to appear epic and big, so you need to do it slowly, or capture a moment in time rather than show a whole process.

The effects are there to support the story, we wanted it to look sweeping and intimate, but also have scale and wonder.

The Planets is now available on DVD and Blu-ray. The DVD includes the full series plus bonus behind the scenes content.

Below is a preview from the DVD of Rob Harvey taking us through some of the special effects created for The Planets.