Pythagoras is a magnificent example of a lunar crater. It’s 129km in diameter and fairly close to the Moon’s northwest limb, and as a consequence it appears rather foreshortened to us on Earth, changing shape due to the effects of lunar libration.

The crater’s rim is surrounded by sloping ramparts rising gently above their surroundings. It appears to terrace its way down to a relatively flat floor approximately 4.8km below.

Apart from the obvious central mountain complex that lies at the centre of the crater, the floor shows little detail until the illumination becomes oblique.

When that happens, you should be able to see a series of low-altitude hills, giving the floor some texture.

For more lunar observing advice, read our guide on how to observe the Moon and the best features on the Moon.

Facts about Pythagoras Crater

- Size: Approximately 129km across

- Longitude/Latitude: 63.0ºW, 63.7ºN

- Age: 1.1-3.2 billion years

- Best time to see: Five days after first quarter or four days after last quarter (6-8 July and 19-21 July)

- Minimum observing equipment: 10x binoculars

The central mountains are particularly striking and extremely useful for quickly identifying Pythagoras.

As is often the case with features closer to the limb, it’s an area in which it is easy to lose your way, but those Pythagorean peaks act as solid navigational beacons.

There are three peaks visible, rising to impressive heights estimated to be around 3km above the crater floor.

Despite providing such stunning signposting when the lighting is right, Pythagoras is surprisingly easy to lose when the Sun is high in the crater’s sky.

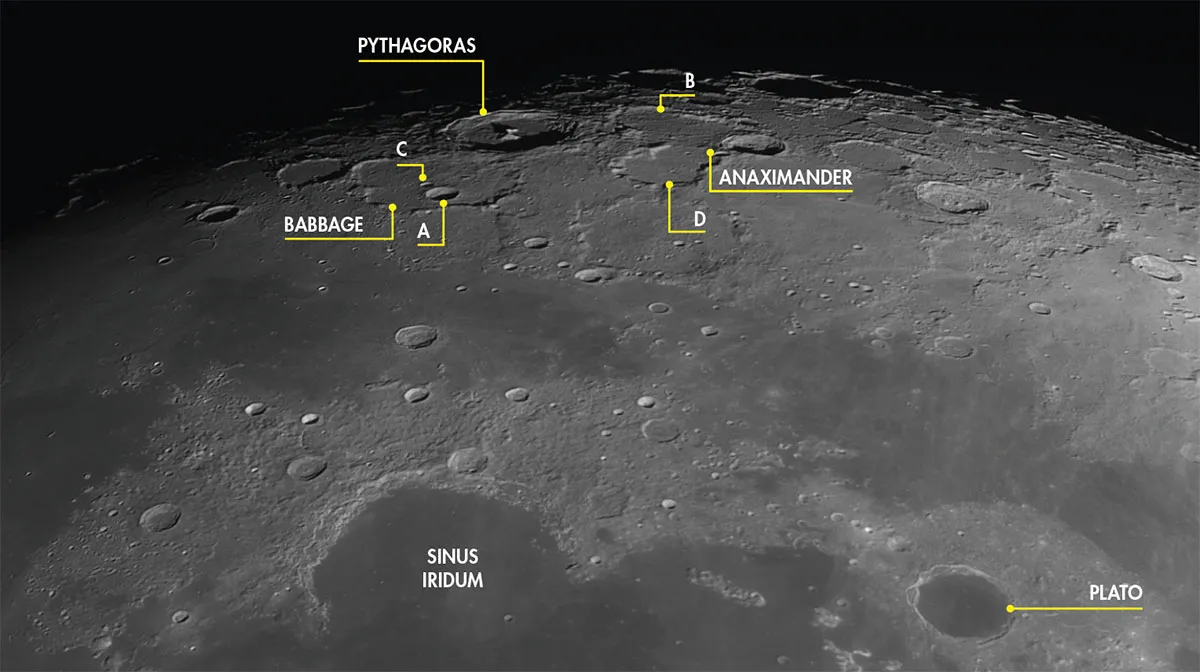

At such times, the best way to locate it is to realise that it forms a right angled triangle with the beautiful semi-circular feature known as Sinus Iridum and the dark floored, circular Plato crater.

Once you realise that Sinus Iridum sits at the right angle of this triangle, finding Pythagoras under full illumination is remarkably straightforward.

Libration plays a big part in the crater’s appearance and when in its least favourable position, Pythagoras sits virtually on the Moon’s limb, giving us a sideways view.

Even when well placed, we are presented with a good view of its western rim terraces, but those to the east appear heavily foreshortened and difficult to discern.

The most prominent features that lie nearby are fairly rugged and irregular in shape.

To the south is 144km crater Babbage, the irregular rim of which contains the more defined forms of Babbage A (26km) and Babbage C (14km) the latter lying right at the centre of Babbage itself.

To the northeast is the curious form of Anaximander (68km). The parent crater here is difficult to see as its floor is conjoined with Anaximander D (92km), and Anaximander B (78km).