Imagine you’re in a woodland, with sunlight filtering through the endless green canopy overhead. There’s uniqueness everywhere.

Some trees grow bolt upright, but others are wizened and twisted. Here the ground is clear, but over there it’s riddled with brambles and thorns.

More mind-blowing science

Yet this individuality fades if you can climb a ridge and lift yourself above the canopy. Now your view is a constant sea of green for as far as the eye can see.

The forest is both regular and directionless.

Most cosmologists believe that the Universe works in the same way.

At small scales, there are individual quirks such as stars, planets and different types of galaxies.

But zoom out far enough, to scales of hundreds of millions of lightyears, and it’s like climbing that ridge: the Universe becomes uniform.

Astronomers say that, on large scales, the Universe is both homogeneous and isotropic.

Homogeneous means the Universe is the same everywhere – drop into any sufficiently large patch of space and, on average, you’d see the same spread of galaxies.

Isotropic means the Universe looks the same in every direction – no matter whether you look north, south, east or west, the broad brushstrokes of the cosmic picture repeat.

Together, these ideas underpin an almost sacrosanct astronomical assumption that’s known as the cosmological principle, which says that we do not occupy a special place in the Universe.

"Homogeneity and isotropy are absolutely central to modern cosmology," says Blake Sherwin, a professor of cosmology at the University of Cambridge.

"If we ever robustly confirmed a departure from them, it would force us to reexamine the foundations of the field."

Beginnings of a scientific revolution

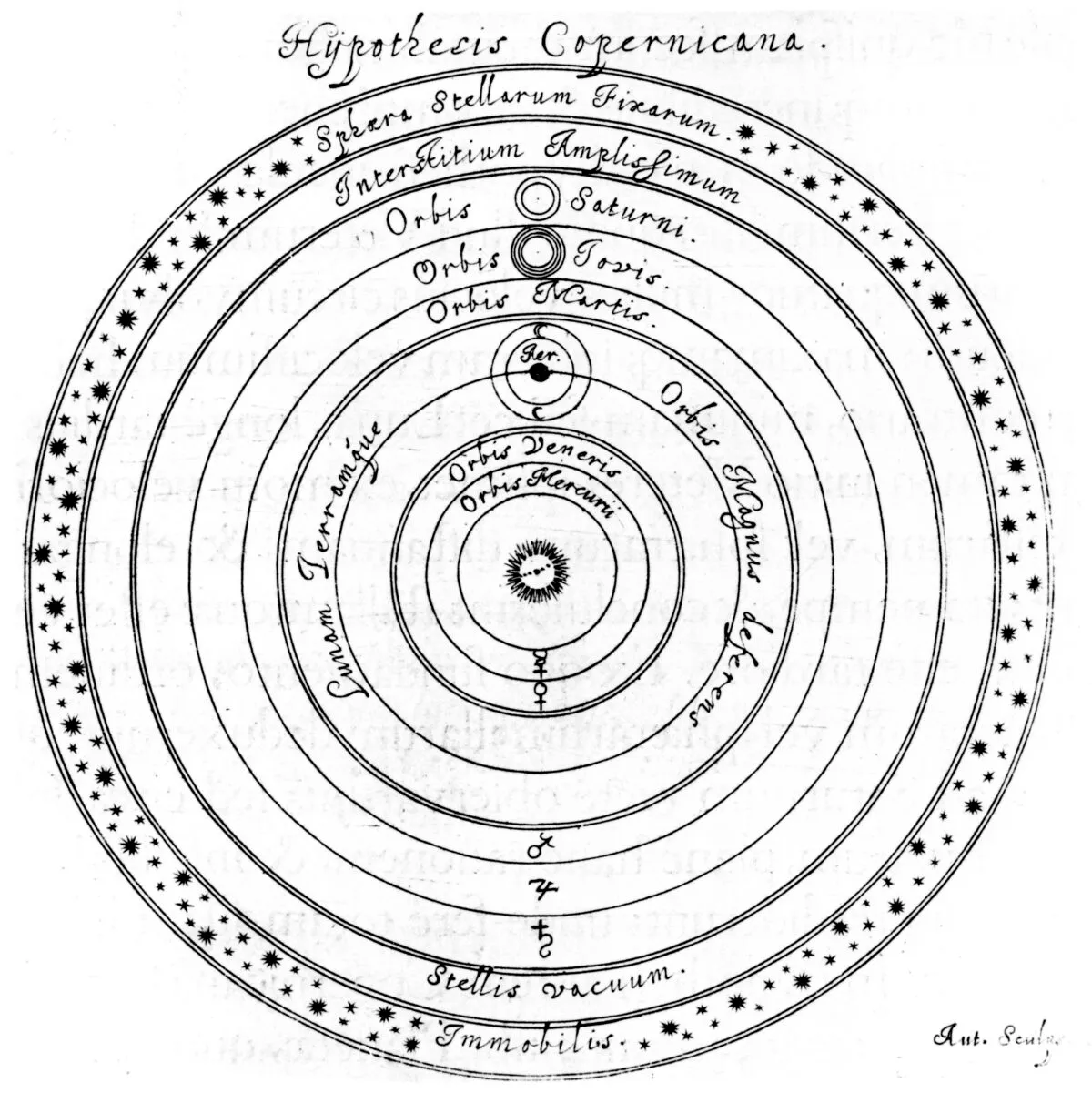

But the idea is much older than modern cosmology. In the 16th century, Nicolaus Copernicus displaced Earth from the centre of the cosmos, demoting it to just one planet orbiting the Sun.

Over time, this insight broadened into the Copernican principle: no location in the Universe is special.

When Isaac Newton used gravity to explain why planets orbit the Sun, he also imagined a Universe filled uniformly with matter.

Only such an even distribution, he argued, could prevent gravity from pulling everything into a single catastrophic collapse.

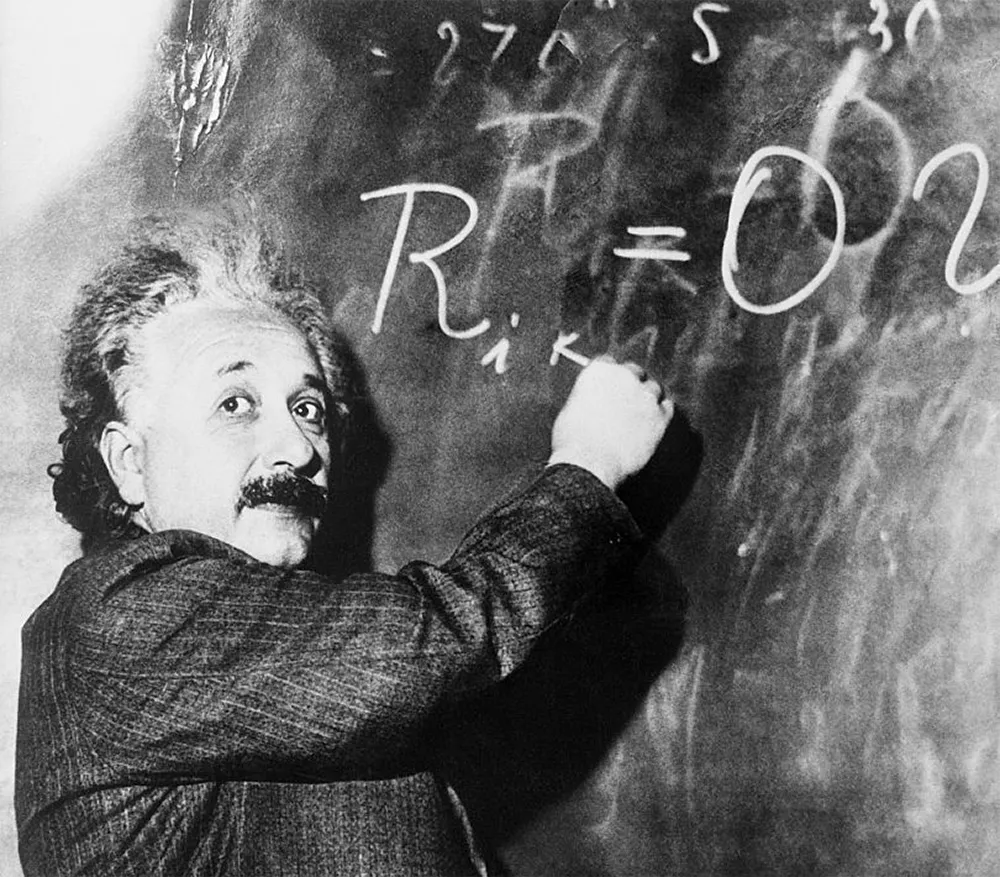

By the 20th century, Einstein’s general theory of relativity had replaced Newton’s ideas as our best description of gravity.

Applying it to the entire Universe was daunting, but assuming the cosmos was homogeneous and isotropic made the task manageable.

In doing so, Alexander Friedmann and Georges Lemaître reached a surprising conclusion: a perfectly static Universe was impossible. Instead, the cosmos must be either expanding or contracting.

Einstein himself was reluctant to accept this and tried to force his equations back into a steady solution.

But in 1929, Edwin Hubble showed that the Universe is indeed expanding, by proving that galaxies are moving away from us.

Lemaître went further, suggesting this expansion must trace back to an initial explosive moment – what we now call the Big Bang.

Cosmic Microwave Background

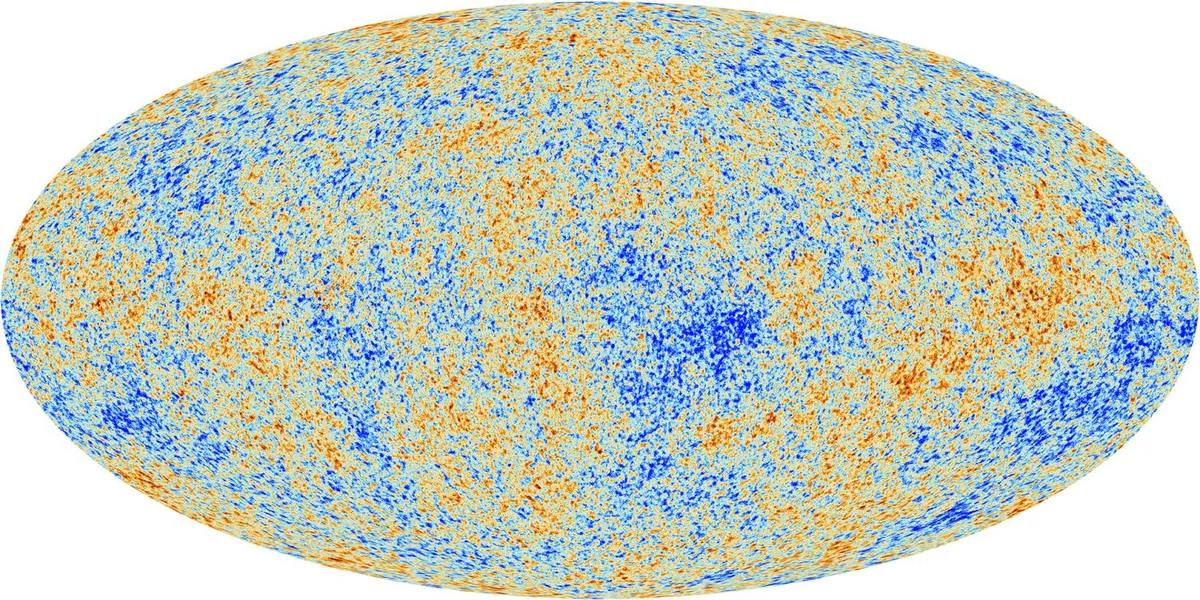

One of the biggest pieces of evidence for the Big Bang is the cosmic microwave background (CMB).

It’s the leftover light from the hot, dense birth of the Universe, released when it was just 380,000 years old.

In turn, the CMB is also an excellent laboratory for testing the twin ideas of homogeneity and isotropy.

"The cosmic microwave background is remarkably uniform in its physical properties," explains Dr David Lagattuta from Durham University.

Its temperature is almost identical throughout, with tiny variations of just one part in 100,000.

This is the result of a period in the Universe’s first slivers of a second, known as cosmic inflation, during which the nascent cosmos ballooned in size by a factor of 1 followed by 78 zeroes.

And yet, there are hints of more complicated patterns in that early signal.

"There are some anomalies in the CMB," says Lagattuta. "One side of the sky looks slightly warmer, the opposite side slightly cooler."

This effect is known as the CMB dipole. At first it might look like a violation of isotropy, but in fact it’s simply due to motion.

As the Solar System ploughs through space, the part of the CMB that we’re moving towards appears hotter, while the part we’re moving away from looks cooler.

Beyond that, some astronomers have claimed to see subtler effects – quadrupoles and octopoles – in the CMB data.

"Interestingly, those differences seem to be aligned with our Solar System," says Lagattuta.

"If we assume that there’s no unique orientation, why is it that those differences seem to be pointing in the same direction?"

They could simply be the result of some unrecognised contamination from our own Galaxy. But if the alignments are real, they would break isotropy.

"It would be quite exciting if it turned out to be real, that there’s some difference in physics that we don’t understand," comments Lagattuta. For now, it remains an open question.

Cosmic clumps and gaps

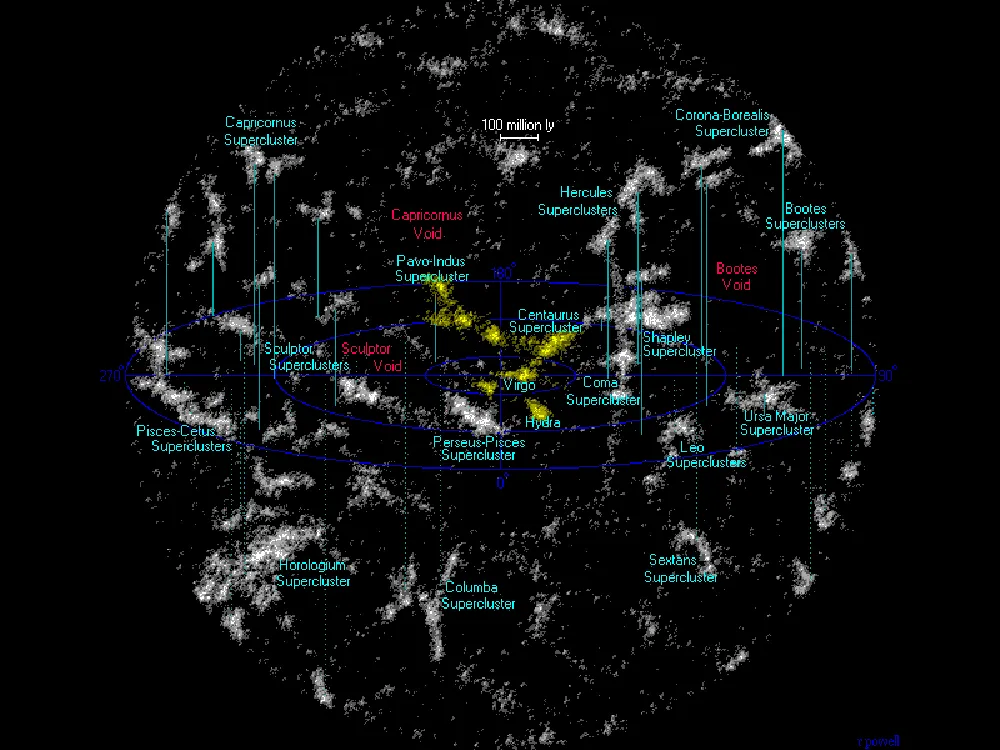

If the CMB is the cleanest test of isotropy, then the large-scale distribution of galaxies is the toughest test of homogeneity.

There is a hierarchy of structure in the Universe. Individual galaxies sit inside clusters, which in turn amass into superclusters.

Superclusters are separated by barren wildernesses known as cosmic supervoids.

It’s on the scale of superclusters and supervoids – around 500 million lightyears – that the Universe is expected to start losing its personality.

Like the canopy of trees in the forest, everything should blur into sameness.

Except that rule doesn’t always hold. Astronomers made headlines in 2021 with the discovery of an enormous crescent structure known as the Giant Arc.

It sits some 9.2 billion lightyears away, but its sheer size is what stands out: nearly 3.3 billion lightyears across, several times larger than the scale at which structures are supposed to fade into uniformity.

The research team, led by Alexia Lopez from the University of Central Lancashire, put the chance of

it being a mere alignment of unrelated objects at just 0.0003%.

Then, in 2024, the same team claimed the discovery of another giant cosmic structure.

Known as the Big Ring, it’s a circle of galaxy clusters measuring 1.3 billion lightyears in diameter.

Remarkably, both the Giant Arc and the Big Ring are located at roughly the same distance from Earth.

They also appear in a similar part of the sky, just 12° apart (the whole sky spans 360°).

Are we in a weird spot?

The Universe is meant to be homogeneous. Drop yourself into any part of it and above a certain scale it should look the same.

Yet if these two structures are real, there’s clearly something unique about this particular spot.

But some cosmologists aren’t ready to get rid of homogeneity and isotropy just yet.

"Personally, I think there’s a high bar for throwing away these foundational principles," says Blake Sherwin.

"If we could, it would be the most interesting thing ever. But the evidence we have so far isn’t enough."

Some, like astroparticle physicist and cosmologist Professor Subir Sarkar at the University of Oxford, argue that what we attribute to dark energy could instead be an illusion caused by the inhomogeneity of enormous structures such as the Giant Arc and Big Ring.

Dark energy is the mysterious entity thought to be driving the accelerating expansion of the Universe.

Astronomers don’t know what it is, but it seems to be a property of space itself, expanding the cosmos uniformly and preserving its large-scale smoothness. At least that’s the mainstream view.

There are even more radical ideas. The Timescape theory suggests that we live in an overly dense part of the Universe and that’s biasing our measurements.

Gravity affects the rate at which time passes, so regions with different masses would expand at different rates.

If we’re observing the cosmos from inside a dense patch, the clock we use to measure the Universe’s expansion may not be representative of the cosmos as a whole.

In this view, dark energy could again be a figment of our imagination.

One recent alternative – and still controversial – view is that the Milky Way is at the centre of a giant void approximately a billion lightyears in radius.

Researchers at the University of Portsmouth have proposed that this may be causing the cosmos to expand faster in our local environment than in other parts.

Right now, it’s hard to say for sure – as always, we need more data.

The Simons Observatory and the South Pole Telescope will continue to probe the CMB for anisotropies (non-uniform variations).

Huge sky surveys, such as Euclid and the Vera Rubin Observatory, are also in the pipeline to map the large-scale structure of the Universe.

But in the end, it all comes down to one question: how special are we, really?