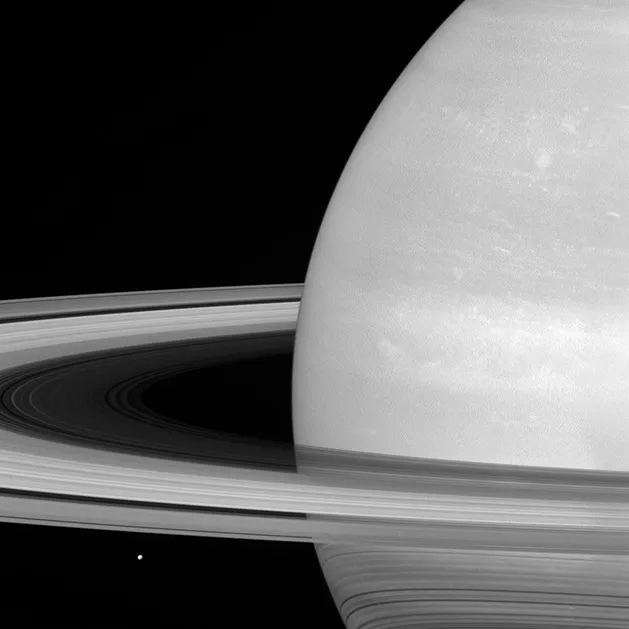

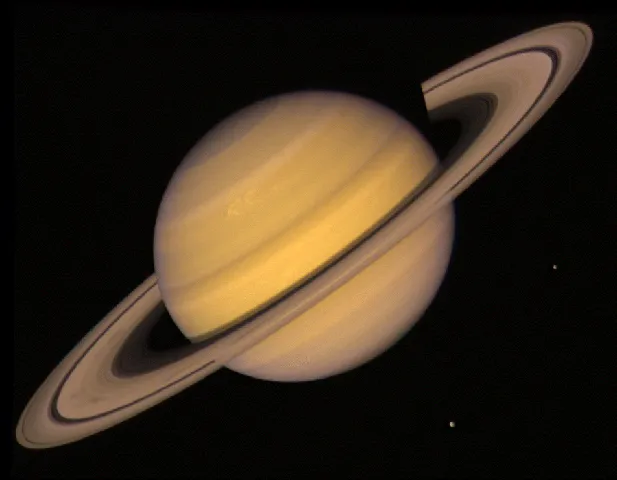

Saturn and its rings may be the most iconic, instantly-recognisable body in the Solar System, after our own planet Earth, of course.

Made mostly of ice, Saturn's rings are an astounding phenomenon, made all the more incredible for us by ventures like the Cassini mission.

It sent back data and images that have taught planetary scientists so much about these amazing features.

But, as we learn in astronomy, nothing lasts forever, and Saturn's rings are disappearing relatively quickly, cosmologically speaking.

Just how much do we know about Saturn, and when will its rings disappear?

James O’Donoghue is a planetary scientist, astronomer and science communicator working at the Japan Aerspace Exploration Agency.

O'Donoghue's research follows the upper atmospheres of giant planets, and we got the chance to ask him about Saturn's rings, and how quickly we might expect them to disappear.

Tell us about Saturn

Saturn is a ‘gas giant planet’ nearly 10 times wider than Earth and made mostly of hydrogen.

It has a ring system and rotates fast; a day on Saturn is just 10 and a half hours.

It’s a very interesting world because of its rings, which have become a symbol of the Solar System – when you look at illustrations that symbolise science at a Science Festival, you’ll almost always see images of Saturn.

What are Saturn’s rings made of?

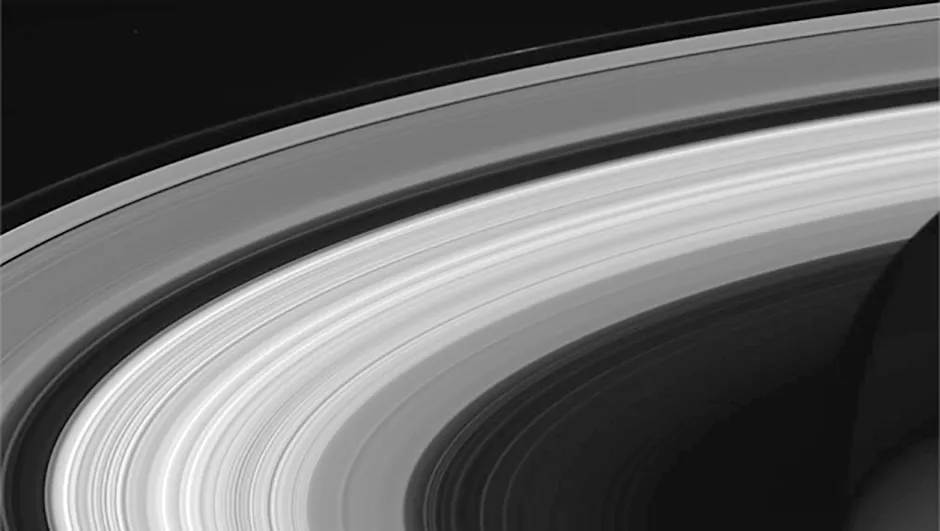

They’re made of ice that is nearly completely composed of water, with a little bit of dust that has been picked up over aeons.

The ice is made of fragments, from dust-sized particles all the way up to bus-sized pieces, which independently orbit Saturn, arranged so that the rings are only several metres in thickness overall.

The fragments are aligned into countless thin tracks, with the inside tracks orbiting the planet faster than the outside tracks.

How old are Saturn's rings?

There’s a huge schism in the field about how old the rings are.

They look very young, as though they were formed hundreds of million of years ago.

But the debate suggests that they could have instead formed around four billion years ago when the Solar System was a much more active place, as the kinds of giant collisions that form rings were much more common back then.

On the other hand, Saturn’s rings look really clean, almost 99% pure water, and that isn’t feasible if they’re billions of years old.

Are Saturn’s rings disappearing?

We think they’re falling into the planet.

We found that there must be a lot of material flowing into Saturn at mid-latitudes, and inferred that the material is water, since that’s what the rings are made of, but it’s likely some of the material is tiny pieces of silicate rock.

We can see this as there is a depletion in the density (or number) of electrons in Saturn’s atmosphere – there are huge bites missing where you don’t expect them.

But why? It’s a complicated chain of chemical reactions but, essentially, the neutral water neutralises charged electrons, reducing the electron density.

This ‘ring rain’ is having a big impact on Saturn’s atmosphere.

In 2017, the Cassini spacecraft found about 10 times more material flowing in at the equator than we found at mid-latitudes.

How long will Saturn’s rings last?

We know the rate at which the rings are falling in and we know their current mass.

Extrapolating that into the future, we predict the rings could last 100 million to 1.1 billion years.

But most likely it’s in the order of hundreds of millions of years.

We still need a lot more evidence – studies from the last few weeks showed it could even be 100 million years or less. I think we can say we’re lucky to be alive at a time when we get to see Saturn’s ring system at all.

What will your team investigate about Saturn next?

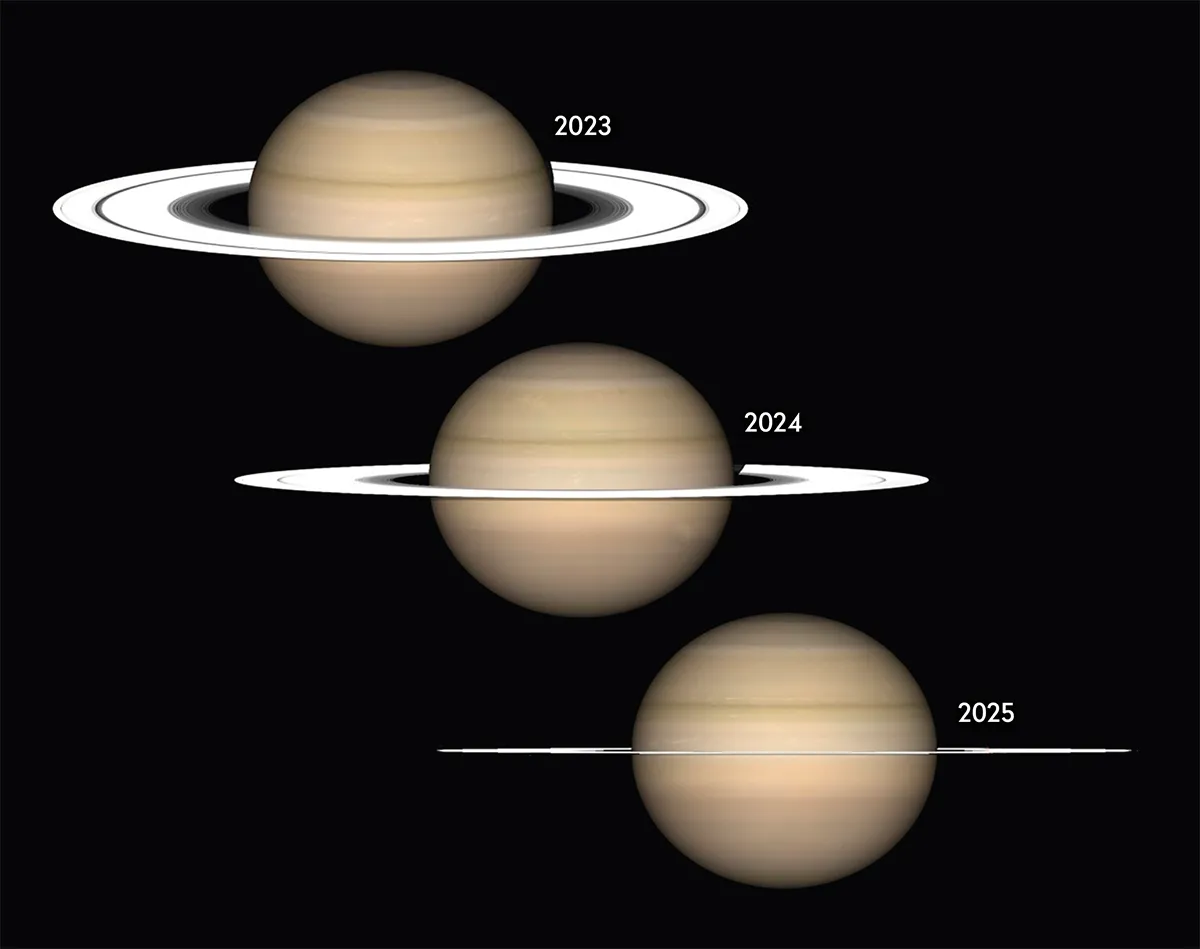

We want to see how ring rain varies with the seasons.

As Saturn progresses through its year, the rings become more or less inclined towards the Sun, exposing the rings to more or less sunlight.

We think ring rain should flow faster when the rings are highly inclined to the Sun, since sunlight charges the ring grains, which allows them to ride into Saturn via the planet’s magnetic field.

Each of Saturn’s seasons lasts nine years.

In 2025, the rings will be edge-on to the Sun and seven years after, they’ll be totally exposed.

We hope to take measurements over the next decade to track the rate of ring rain over time and multiply it by four to understand what happens in a year at Saturn (29 Earth years).

We also want to use the James Webb Space Telescope’s ridiculously high sensitivity to see if we can get a more precise estimate of the ring rain’s influx, which will help us to be more precise about the rings’ current erosion rate and future lifetime.

This interview originally appeared in the August 2023 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.