Our journey begins about 1,500 years ago when the earliest surviving Arabic poetry was orally recited by nomadic poets living in the Arabian Peninsula. At this time, the sky looked somewhat different, and not just because the Arabian Peninsula lies further south than Europe.

Earth wobbles as it rotates, causing its celestial poles to trace a circle across the sky over the course of almost 26,000 years; a process called precession of the equinoxes.

As a result, pre-Islamic Arabian skies had no North Star. Instead, a stellar trio that danced around the North Celestial Pole marked the direction of north. One you may know as Polaris, our current North Star; in Arabia, this was called the Goat Kid (al-jady الجدي) .

The others were a pair of stars called the Two Wild Cow Calves (al-farqadān الفرقدان); today these are known as Pherkad (from al-farqadān) and Kochab (from kawkab, meaning “star”). These stars were used by camel caravan drivers for navigating the shifting sands of the desert.

Read more:

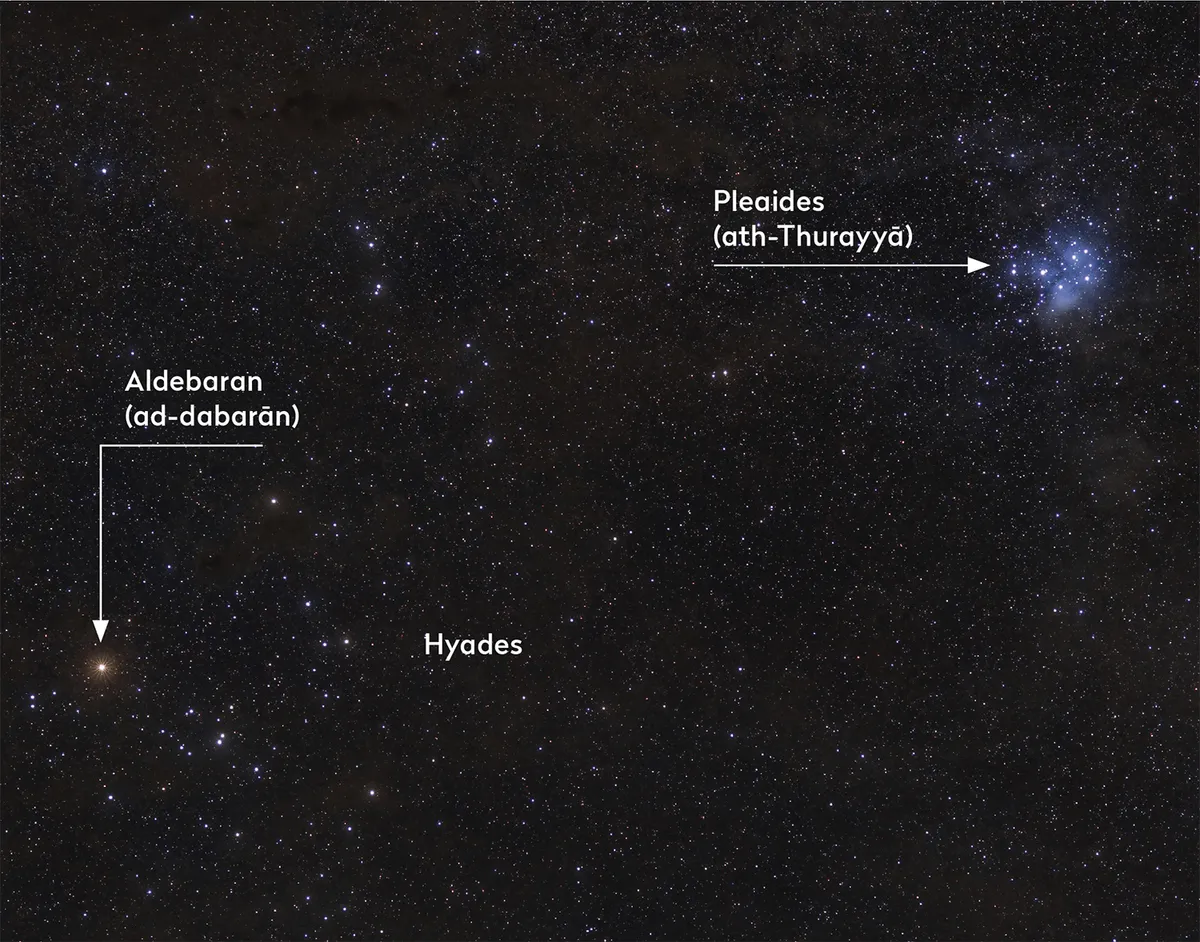

One story that has survived the ravages of time involves a brilliant red supergiant you may know as Aldebaran, the Follower (ad-dabarān الدبران).

Just ahead of the Follower is the famed Pleiades star cluster, which was known in Arabia as ath-Thurayyā الثريا. She was in love with the Follower, but the Impeder (al-‘ayyūq العيوق, the star Capella) prevented them from getting together.

Now the Follower forever chases ath-Thurayyā across the sky as the Impeder watches them from high above.

Ath-Thurayyā was so celebrated in Arabia that it was often mentioned simply as “the Star” (an-najm, indicating a single star or small asterism).

Over time it gained two arms, one of which extends into modern-day Cetus while the other passes through Perseus to a five-fingered hand represented by the stars of Cassiopeia.

Several modern star names point to the storied arms of ath-Thurayyā (kaff ath-Thurayyā, كف الثريا), including Caph (from kaff, meaning “hand”), Mirfak (al-mirfaq, المرفق) (from mirfaq, meaning “elbow”) and Menkib (al-mankib, المنكب) (from mankib, meaning “shoulder”).

The motions of the stars were watched closely in Arabia, as their positions at specific times of the night indicated seasonal changes.

“When the Star rises at nightfall, the herdsman earnestly seeks a cloth wrap,” was a common saying pointing to the cold weather that arrived when ath-Thurayyā rose in the east as the Sun set in the west.

More often it was the setting of stars at the end of the night that predicted seasonal changes. Autumn rains began at the dawn setting of two stars known as the Two Vultures (an-nasrān, النسران).

One of these two stars you may know as Vega, its name derived from its Arabic name the Alighting Vulture (an-nasr al-wāqi‘ النسر الواقع).

This vulture was imagined as having its wings stretched back as it prepared to land, because it forms a small V shape with the two nearby stars epsilon and zeta LYR.

The other vulture star is Altair, known as the Flying Vulture (an-nasr at-tā’ir النسر الطائر) because its nearby stars form a straight line like the wings of a soaring bird.

After the development of Islam in 622 CE and its proliferation outside of Arabia, Greek constellations were eventually grafted into Islamic astronomy.

For example, Deneb comes from the Arabic dhanb ad-dajjāja ذنب الدجاجة, meaning “the tail of the fowl,” which indicates the star’s position in the tail of the Greek swan, Cygnus.

Some Greek constellations were given indigenous Arabian star names used elsewhere. The four stars that comprise the modern Square of Pegasus were known well before 622 as the Well Bucket (ad-dalw), because they resembled the shape of a bucket formed from a leather pouch by crossing two sticks at its mouth.

Later, the name ad-dalw was given to Greek Aquarius, the water-bearer who holds a bucket. Today, if you ask an Arab friend which constellation ad-dalw is, they will point you to Aquarius, not Pegasus.

The modern night sky showcases the remains of cultural interactions that span millennia. When you look up at the night sky, consider the great heritage of Arabian astronomy that endures to this day.

Dr. Danielle Adams is Deputy Director at Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona. For more info on Arabian astronomy, visit her website onesky.arizona.edu. This article originally appeared in the December 2019 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.