Charon is the largest moon that orbits Pluto, and it is also the innermost moon around the dwarf planet. It was discovered on 22 June 1978 by astronomers James Christy and Robert Harrington.

The morning of its discovery, astronomer James Christy’s thoughts were not on the sky, but on his plans to move house.

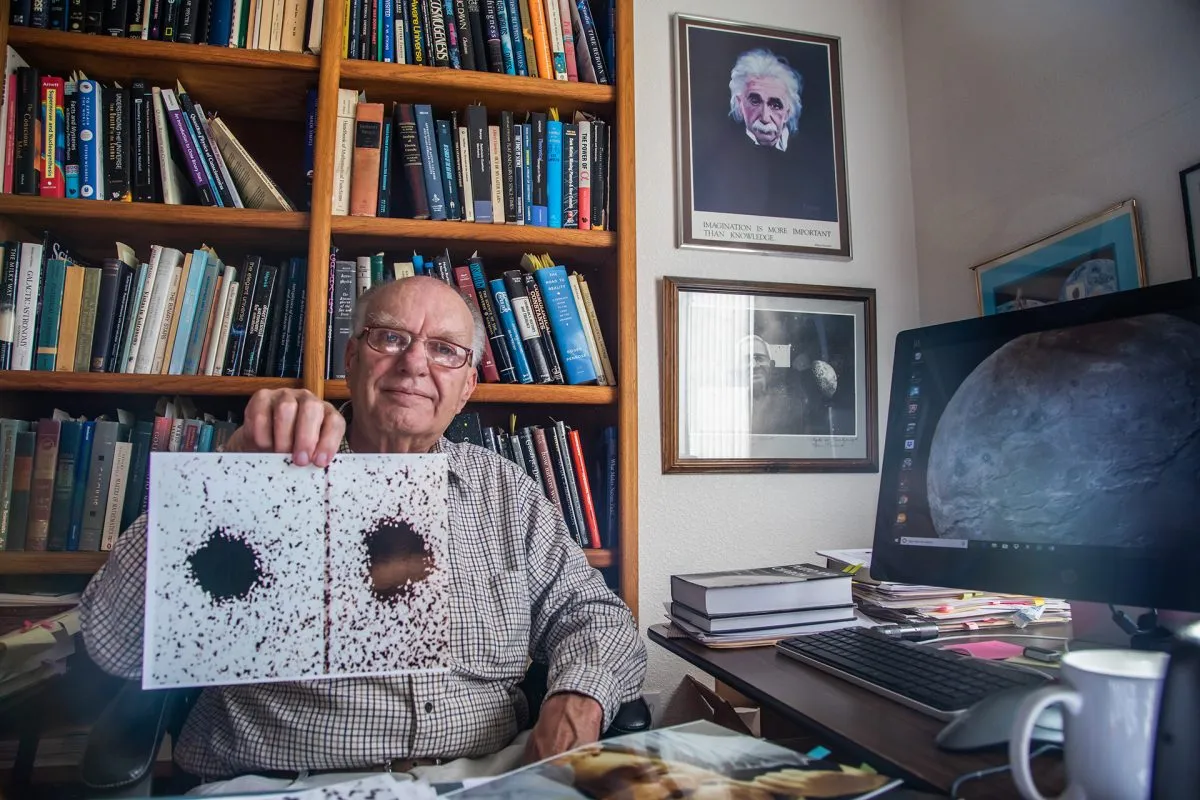

He was ready for a week’s leave from the U.S. Naval Observatory when his boss, Robert Harrington, handed him six images of Pluto.

They had been taken earlier in the year and Christy intended to use them to plot the orbital elements of a tiny world, 7.5 billion kilometres away, about which little was known with certainty.

On the face of it, the images did not look good.

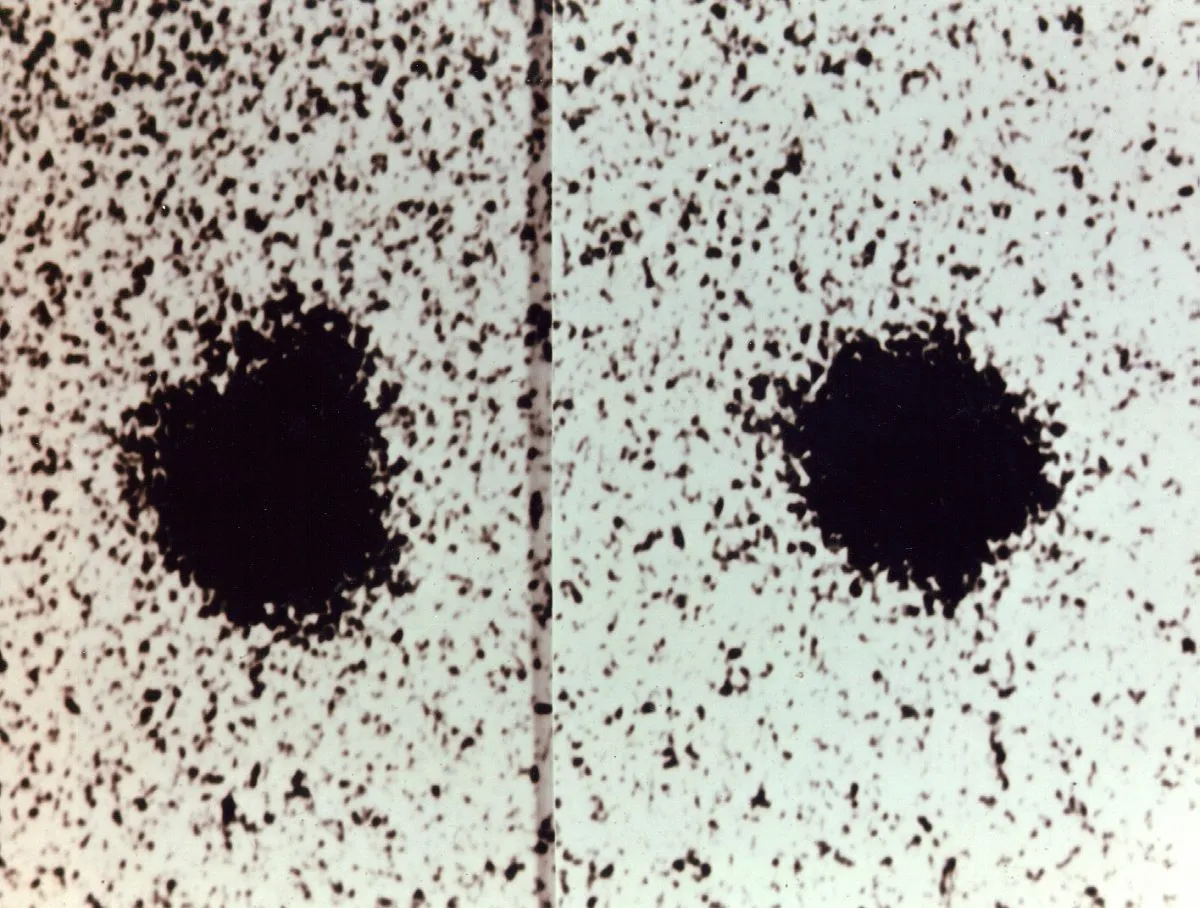

Labelled ‘defective’, they were acquired in pairs over three nights between 13 April and 12 May and revealed Pluto to be oddly elongated.

Christy amplified them under a microscope. The fuzzy blob appeared stretched in a northward direction in the first two pairs and in a southward direction in the final pair.

The images came from the Naval Observatory’s 1.5-metre Kaj Strand telescope in Flagstaff, Arizona, and the peculiarity was attributed to improper optical alignment or atmospheric distortion.

None of the background stars was affected, leading Christy to wonder if an explosion had happened on Pluto and it seemed unlikely that such an event would last an entire month.

Next, he pondered the existence of an unseen moon, but one of his former professors, the celebrated astronomer Gerard Kuiper, had performed a thorough search, decades earlier, without success.

It was also plausible that Pluto was simply irregular in shape.

Checks of star positions at the time the images were taken also drew a blank.

On 23 June, Christy dug through older plates from 1965 and 1970 and spotted the same elongation.

These, too, had been dismissed as defective. But now they enabled Christy and Harrington to estimate an unseen moon’s orbital period at 6.4 days, matching Pluto’s rotation rate and suggesting a synchronously ‘locked’ binary system.

The Naval Observatory announced the discovery of ‘S/1978 P1’ in July and Christy and Harrington published their findings in the Astronomical Journal.

They demonstrated its orbital elements and distance - closer than any known planet-satellite pairing - and revealed it to be half the size and a seventh as massive as Pluto.

Christy wanted to exercise discoverer’s rights by naming it for his wife, Charlene.

His Naval Observatory colleagues had already suggested Persephone, the wife of Hades, lord of the underworld and the Greek equivalent of the Roman god Pluto.

Then, Christy spotted a reference to Charon, the boatman who ferried the dead across the River Styx to Hades.

The similarity between Charon and Charlene was unmistakable. And Christy knew that many physicists picked weird names for newly-found particles and suffixed them with ‘on’.

Charlene’s nickname was ‘Char’, so ‘Char-on’ fit perfectly.

The name was accepted by the International Astronomical Union in January 1986.

By then, a series of mutual eclipses enabled astronomers to peg Charon’s diameter at 1,200 kilometres and greatly refined the size and mass of Pluto itself.

The next set of mutual eclipses are not expected until 2103.

Had Christy and Harrington ignored those six ‘defective’ images, tiny Charon might still be unknown to us.

For as Christy himself once observed: “Discovery is where the scientist touches nature in its least predictable aspect.”