Archive data from 30 years ago is giving scientists astonishing insight into Venus, our poisonous, scorched, neighbouring planet.

Data from NASA's Magellan mission suggests Venus could be more geologically active than previously thought.

The data shows compelling evidence for ongoing tectonic activity shaping Venus's surface features.

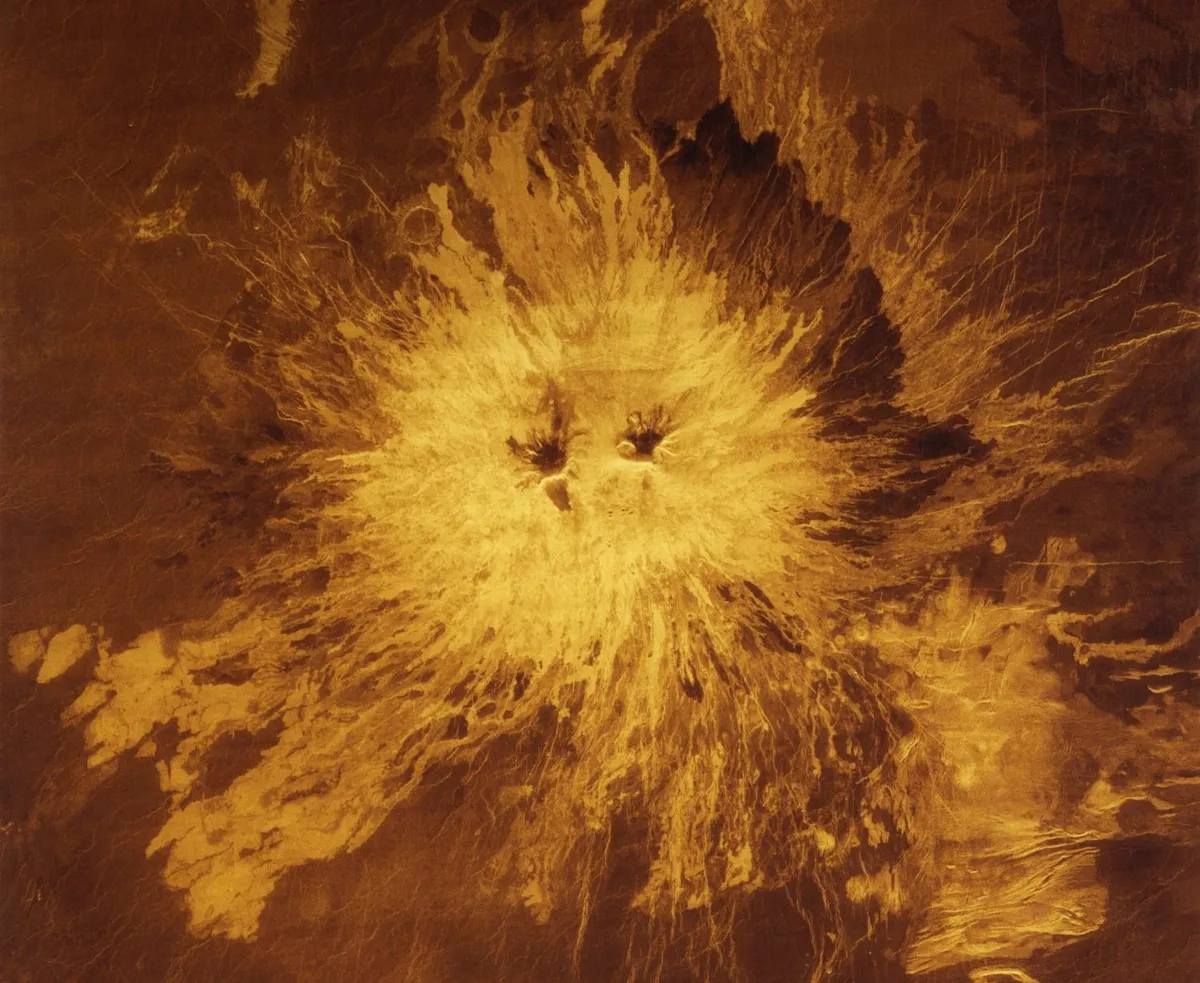

Vast, quasi-circular structures known as coronae could be key to understanding what's going on underneath the surface of Venus.

Earth's sibling, with a twist...

While Venus doesn't have tectonic plates like Earth does, its surface features are being deformed by molten material welling up from below the surface.

Colossal formations called 'coronae' stretch dozens to hundreds of miles across and are thought to form when a plume of hot, buoyant material from the planet’s mantle pushes upwards against the surface.

Hundreds of coronae dot the Venusian landscape.

Diving into Magellan's trove of data

This study, published in Science Advances, looks at gravity and topography data from the Magellan mission, which arrived at Venus in 1990.

Magellan made the first global map of Venus's surface and global maps of its gravity field.

This rich dataset, the most detailed of its kind for Venus, has revealed previously unseen signs of subsurface activity.

Lead author of the study Gael Cascioli says coronae, while absent on Earth today, may have existed when our planet was very young, before plate tectonics took hold.

Therefore, studying Venus's present could reveal more about Earth's history.

Gravity holds the key

The team combined gravity and topography data to effectively peer beneath the surface of BVenus.

Gravity data enabled the team to detect buoyant mantle plumes that were invisible in topography data alone.

The study suggests that subduction, where one crustal section slides beneath another, could be occurring around the edges of some coronae.

And they also found evidence for lithospheric dripping, where dense material sinks into the planet's mantle, as well as plumes of molten rock driving potential volcanism on Venus.

This study suggests geologic processes occurring on Venus are more Earth-like than originally thought.

To the future with VERITAS

Planetary scientists will learn more about Venus when the VERITAS spacecraft arrives at the planet.

VERITAS will use radar to create 3D global maps of Venus and a spectrometer to find out what the planet's surface is made of.

It will also measure Venus's gravitational field to determine the structure of the planet's interior.

"The VERITAS gravity maps of Venus will boost the resolution by at least a factor of two to four, depending on location, a level of detail that could revolutionise our understanding of Venus’s geology and implications for early Earth," says study coauthor Suzanne Smrekar, a planetary scientist at JPL and principal investigator for VERITAS.

Read the full study via www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.adt5932