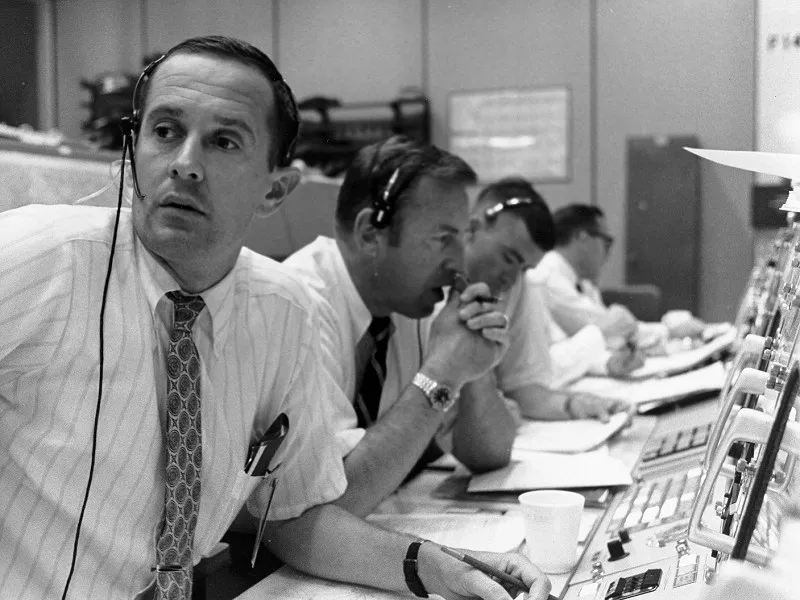

Mission Operations Control Room (MOCR) in Building 30 at NASA’s Houston centre - where engineers worked behind the scenes to land Apollo 11 on the Moon - resembled nothing so much as the villain’s headquarters from a James Bond movie: a four-tiered auditorium crammed with state-of-the-art technology, dominated by a huge bank of video screens and overlooked by a glass-walled viewing room.

For eight days in July 1969, the world’s attention was focused on this building and its occupants, almost as much as it was on the three Apollo 11 astronauts.

From the instant Apollo 11 cleared the tower until it splashed down in the Pacific Ocean, the windowless mission control at the Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston, Texas, and its 30 controllers were in overall charge of the spacecraft and its crew.

- The story behind the Apollo 11 mission patch

- Apollo 11 on TV: how NASA filmed the Moon landing

- Apollo Moon landing conspiracy theories crushed

Since opening in 1963, the Manned Spaceflight Center (now called the Johnson Space Center) had been the hub of the agency’s operations – not just during missions, but also through much of the technology development and astronaut training programmes.

Other buildings on the site housed the Space Environment Simulation Laboratory, used for testing spacecraft in launch and flight conditions, and the Space Vehicle Mockup Facility, used for training the astronauts and in-flight tests – most famously during the Apollo 13 crisis.

There were machine shops for inspecting components, and the Communications and Tracking Center for routing data to and from tracking stations around the world.

The Lunar Receiving Laboratory, meanwhile, would house the astronauts and their samples during a quarantine period after their return to Earth.

Building 30 was the centre of it all. Its control room, with its four rows of grey IBM computer consoles, gauges, dials and meters, monitored some 1,500 items of constantly changing information.

Within the control room, teams of mission experts worked round the clock during missions, overlapping with each other in four eight-hour shifts codenamed green, white, black and maroon.

These controllers’ average age was only 32, and most had degrees in engineering, mathematics or physics.

Each team was responsible to a flight director; maroon team was led by Milt Windler, black by Glynn Lunney, white by Gene Kranz and green by Cliff Charlesworth, who was in overall charge of the Apollo 11 mission.

Maintaining constant contact

Electronic data from the spacecraft – telemetry – was continually routed to the control room’s various desks via NASA’s Manned Space Flight Network, the global network of tracking stations that was capable of maintaining constant contact with Apollo (except when the spacecraft’s orbit took it behind the Moon).

The main map screen at the front of the room, meanwhile, carried a Mercator projection of Earth, tracking Apollo 11’s relative position above the surface and the locations of the different tracking stations.

Large screens to either side of this carried telemetry data, television pictures, and other information from space.

The flight director’s desk in the centre of the third tier gave him an overview of the entire control room.

Each rank of desks played a different role, and each desk had a designated codename. At the front was ‘the Trench’.

Responsible for all aspects of the Apollo spacecraft’s flight to and from the Moon, this was the front line of the operation.

Here, the spacecraft’s computers, guidance systems and fuel tanks were monitored, and exact times for retrorocket firings and manoeuvres were calculated.

On the second row sat the flight surgeon, whose computer console flashed with lights monitoring the astronauts’ heartbeats and breathing, and the ‘eecom’, who was responsible for monitoring the spacecraft’s electrical and life-support status.

Also here was ‘capcom’, the capsule communicator.

Throughout the flight all communication between mission control and the astronauts went through him.

This vital role was always filled by an astronaut, and during Apollo 11, seven of them filled the post, including Charlie Duke, whose distinctive southern drawl guided the lunar module down to the Sea of Tranquility.

On the other side of the second tier were desks concerned specifically with the lunar module and its equipment.

Then, flanking the flight director and his assistant on the third tier were positions concerned with the overall progress and planning of the mission.

These technicians were busy acquiring and distributing data from the network of tracking stations, and monitoring the huge number of carefully planned procedures in the mission’s detailed schedule on a minute-by-minute basis.

The back row consisted of a number of senior personnel who were less directly concerned with the detailed operation of the mission – the public affairs officer, Department of Defense liaison, the mission director from NASA HQ in Washington, DC, and the director of flight crew operations, known unofficially as the ‘chief astronaut’.

This pivotal role was held by Deke Slayton, who had trained with NASA’s original Mercury Seven astronaut team, only to be sidelined when doctors discovered an irregular heartbeat.

But there was more in Building 30 than just the MOCR. Each console had a dedicated room of support staff located down the hall, manned by a dozen experts.

This was where complete data streams from the spacecraft arrived and the most important parts were skimmed off and sent to the control room.

There were separate back rooms for operations and procedures, flight crew, life systems, spacecraft systems and flight dynamics.

Also on hand were staff from Apollo’s major contractors like North American Rockwell and Grumman, in case of trouble with the spacecraft’s equipment.

Mission control also had contact details for up to 40,000 key engineers from the project’s major subcontractors, in case they needed to be contacted urgently.

The teams in the control room were constantly watched by visitors in the glass-walled seating area.

These guests included the crew’s families, other members of the astronaut corps, the media and various VIPs.

Frequent visitors were Bob Gilruth, director of the Manned Spaceflight Center, and Chris Kraft, his deputy.

Gilruth had been charged by President Eisenhower with putting an American in space before a Soviet cosmonaut, while Kraft had worked out the basic requirements of mission control and how they could be implemented in the days of Project Mercury in the late 1950s.

Both men were acutely aware of how much the three astronauts out in space were relying on the expertise in the MOCR in front of them.

Giles Sparrow is an author and science writer. This article originally appeared in the Man on the Moon special edition magazine.