From exploring the surfaces of the Moon and Mars to mapping the dark Universe, 2022 is set to be a big year for space science.

Here are some of the biggest moments in spaceflight and space science to look forward to in 2022.

1

A crewed return to the Moon

Since the Apollo and Soviet missions of the 1960s and 1970s, the Moon has been largely overlooked by space explorers.

But that is about to change as dozens of nations and even private companies are set to visit our nearest neighbour in 2022.

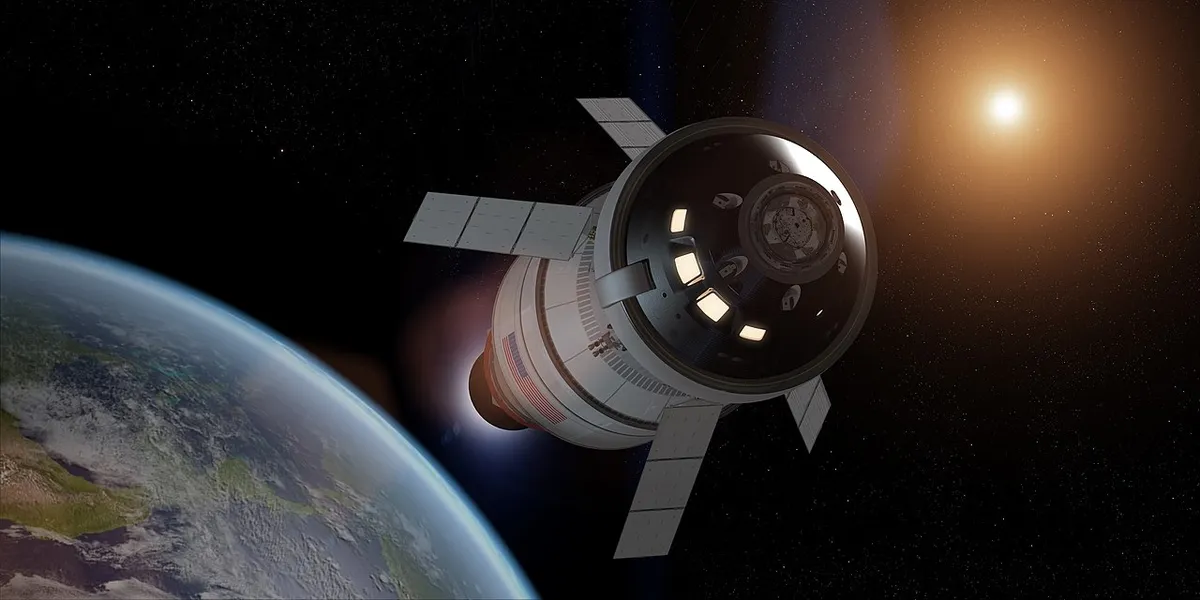

The biggest of these is the Artemis I mission, the first stage of NASA’s endeavour to return to the Moon with a female moonwalker.

Artemis I will be uncrewed, acting as a test for both the Orion crew capsule that will carry astronauts into lunar orbit and the Saturn V-sized Space Launch System (SLS) that will propel them there.

The launch assembly is already fully ‘stacked’ and, once cleared for flight, could be on its way skywards as soon as 12 February.

If all goes to plan, the Orion module will take the same flight path as the future crewed missions to the Moon and then spend several days in lunar orbit, before returning to splashdown in the Pacific Ocean.

2

Lunar landers and exploration

While Artemis I is paving the way for human landings, robotic landers are leaping on ahead, with missions from all over the globe set to land, rove and even scuttle across the Moon’s surface this year.

Most are heading towards the southern pole, drawn by the water ice hiding in the shadowed corners of craters there, which makes the region a leading candidate for a long-term lunar base.

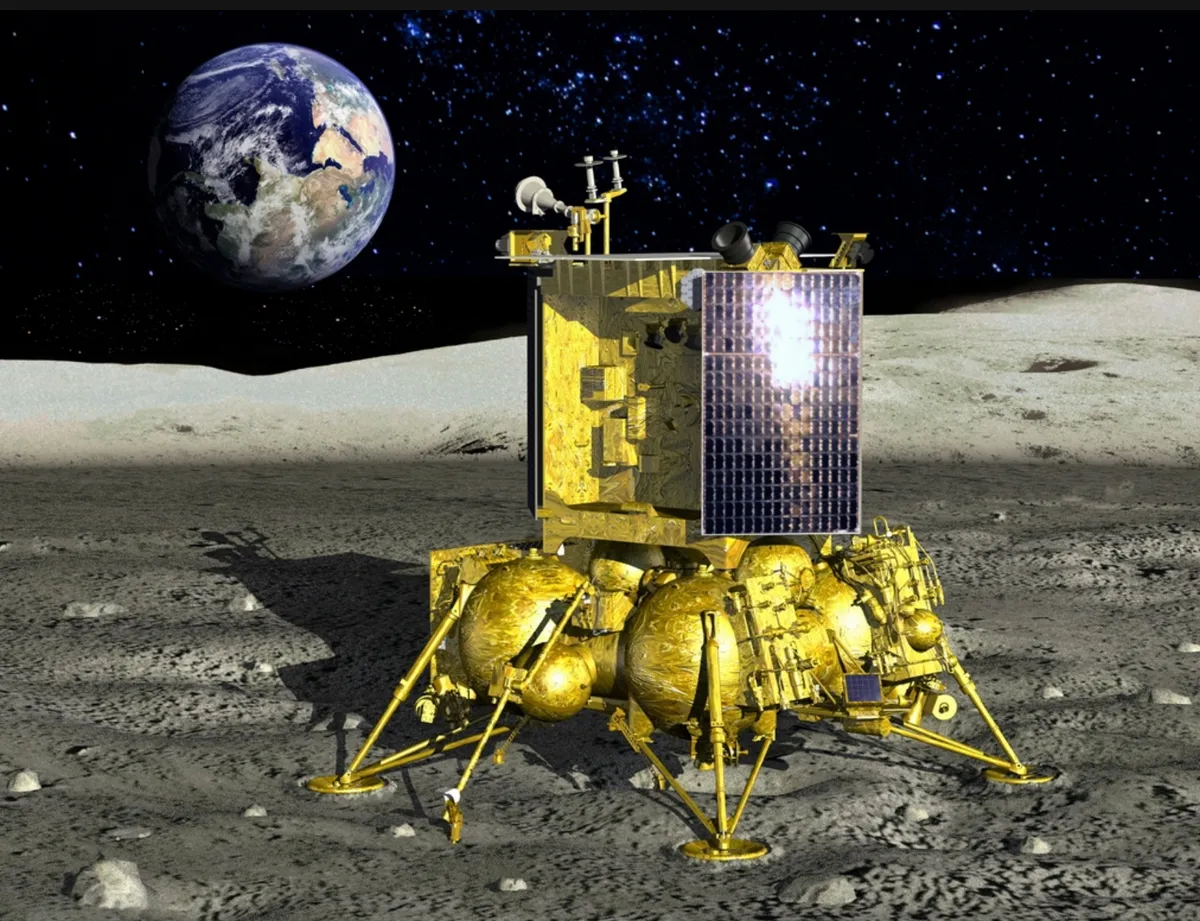

Of those attempting to land, Russia undoubtably has the most experience, with eight successful lunar landings under its belt.

Although the last of these, Luna 24, was in 1976 they are picking up where they left off, nominally at least, and Luna 25 is due to launch in July.

The lander is due to take a sample of lunar soil, known as regolith, and return it to Earth.

In the second half of the year, the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) will be making a second lunar landing attempt with Chandrayaan-3, a rerun of the mission which crashed on approach on 22 July 2019 due to a software glitch.

Provided ISRO achieves a successful landing, the Vikram rover will be released onto the surface, and together the two will explore the lunar pole’s environment.

Vikram won’t be the only rover heading to the Moon, however, thanks to the Peregrine lander being built by private spaceflight company Astrobotic.

Funded by NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services initiative, Peregrine has been specifically designed as a platform to carry all manner of payloads to the surface.

Though the landing platform has never been tested in space, there are plenty of organisations that are willing to hitch a ride.

As well as 14 NASA instruments, the lander will have six rovers, including the spider-like Asagumo walking rover from the UK-based company Spacebit.

Once it has proven itself, NASA plans on using the Peregrine lander to carry the much larger Volatiles Investigation Polar Exploration Rover (VIPER) in 2023, which will investigate water in the polar region.

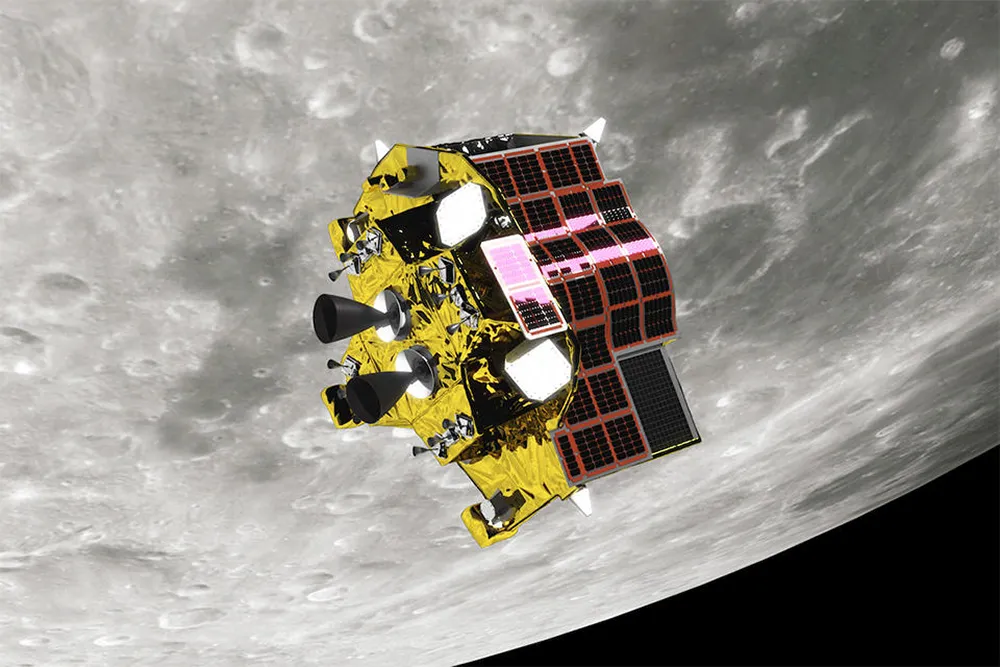

Not everyone is aiming for the lunar south pole, however. The Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency’s Smart Lander for Investigating Moon (SLIM), is instead heading for the Marius Hills Hole, a lava tube near the Moon’s equator.

The mission will aim for a landing area just 100m wide, using the same software used in facial recognition to attain the most precise landing ever made.

Finally, South Korea will be make its first foray into planetary exploration in August with the Korean Pathfinder Lunar Orbiter, in collaboration with NASA.

The orbiter will examine the mineral composition of the Moon and its varied volcanic deposits.

Fifty years after the Apollo missions, it looks like the Moon is firmly back on the top of every space agencies’ priority list.

3

Investigating the small worlds of the Solar System

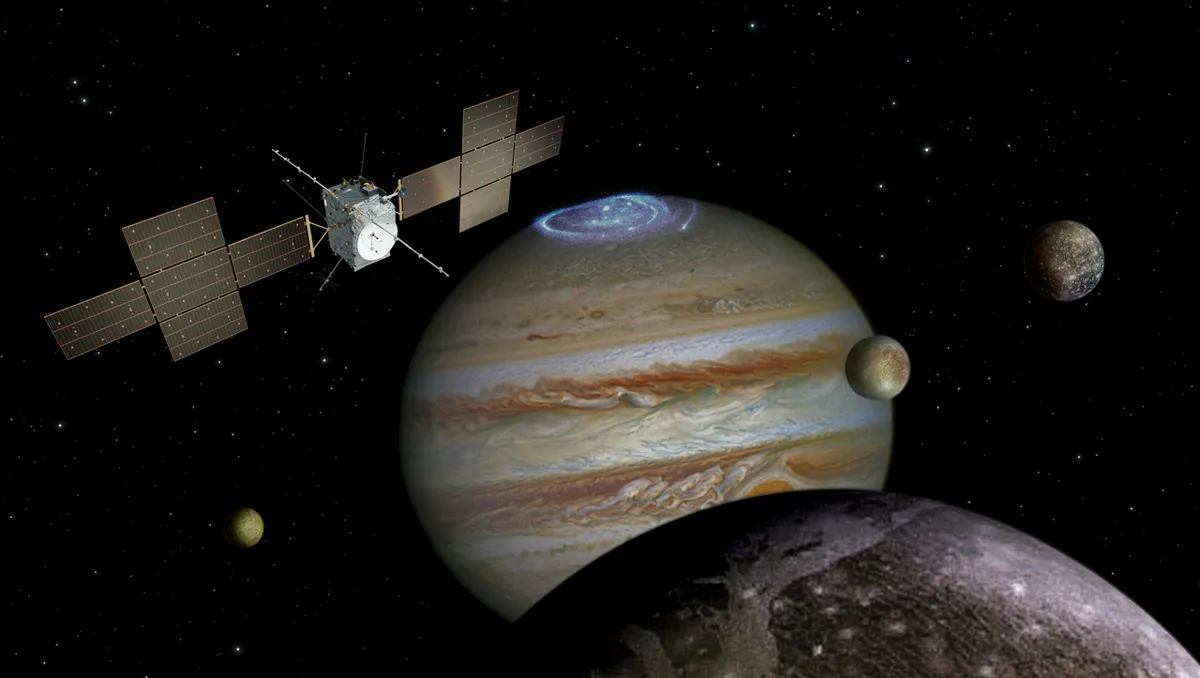

ESA’s Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (JUICE) is due to launch in May 2022 and arrive at Jupiter seven years later.

Once there, it will turn is gaze towards the frigid Galilean moons Europa, Ganymede and Callisto.

Skimming past them around 30 times, it will examine their gravity and magnetic fields to reveal the oceans under the ice, which may be the most likely place to find extraterrestrial life in our Solar System.

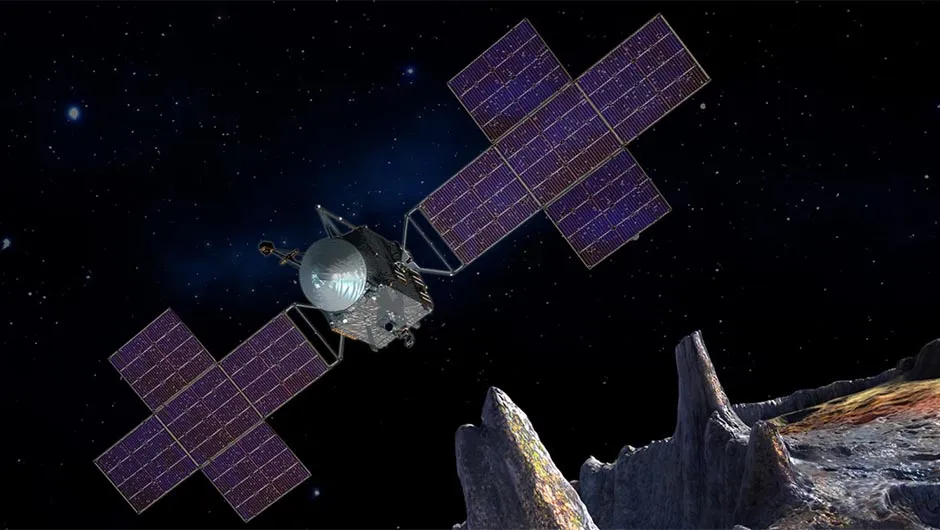

Then in August, NASA’s Psyche mission will head for the metal-rich asteroid that gives the mission its name.

Asteroids are the remnants of would-be planets that were destroyed early in the Solar System’s history, and metal asteroids are believed to have originated in the cores of these planets, meaning geologists can finally investigate part of a planet usually hidden beneath thousands of kilometres of rock.

The most dramatic event, however, is due on 2 October when NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirect Test (DART) will slam into the moon of asteroid Didymos.

The collision should change the moon’s orbit – a test of technology that could one day be used to deflect a much larger asteroid from colliding with Earth.

4

Revealing the dark side of the Universe

The dark side of the Universe is due for a little illumination as the Vera Rubin Observatory in Chile is set to see first light this year, ahead of going into full operation in 2023.

The telescope will use its 8.4m-wide mirror to image 18,000 square degrees of sky – almost half of the celestial sphere – over 800 times.

The goal of this momentous observing campaign is to map the distribution of mysterious dark matter threading throughout the Universe, and understand the even more enigmatic dark energy driving it apart.

The observatory will be able to get such a refined level of detail, even on distant galaxies, that astronomers can look for an effect known as weak gravitational lensing, where the light from distant galaxies is bent as it passes by large masses.

As most of this mass is dark matter, these lenses can reveal the distribution of the otherwise invisible substance.

Vera Rubin will also help our understanding of dark energy, a theoretical force which forces galaxies apart, by helping to measure how fast the Universe has been expanding over time.

5

A new era for human spaceflight

The year 2021 was a turning point for private human spaceflight, with both Virgin Galactic and Blue Origin launching space tourists for the first time.

But after a year of troubles, Boeing is hoping 2022 will be its year. Its issues began in December 2019 when the first uncrewed test of its Starliner crew capsule failed to reach the International Space Station.

Then a repeat attempt in August was called off at the last minute when some fuel valves failed to open.

Boeing plans to launch in the first half of 2022, paving the way for a crewed test later in the year.

Elsewhere, the Chinese space agency will finish the construction of its space station, adding the Wentian and Mengtian lab modules.

And finally, the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) will take the first steps in creating its own human spaceflight programme, with the inaugural flight of its Gaganyaan 1 crew module.

Though this test will be uncrewed, the ISRO hopes to carry its first ‘vyomanauts’ into orbit as soon as 2023 and ultimately build its own space station.

6

The Great British space race

In summer 2021 the first licenses for rocket launches from UK soil were given, meaning 2022 looks set to be the start of the ‘Great British Space Race’ as spaceports compete to launch first.

Spaceport Cornwall, based at Newquay airport, is the UK’s only horizontal spaceport, meaning traditional planes are used for the first section of the ascent.

The first launch from the port is likely to be Kernow Sat 1, a Cornwall-designed Earth observation satellite that will launched by Virgin Orbit.

Meanwhile, the SaxaVord Spaceport on Unst in the Shetland Isles hopes to launch the first of the UK Space Agency’s Vertical Launch Pathfinder Programme.

And another Scottish spaceport, based in Sutherland, is commencing construction with a goal of launching by the end of 2022.

7

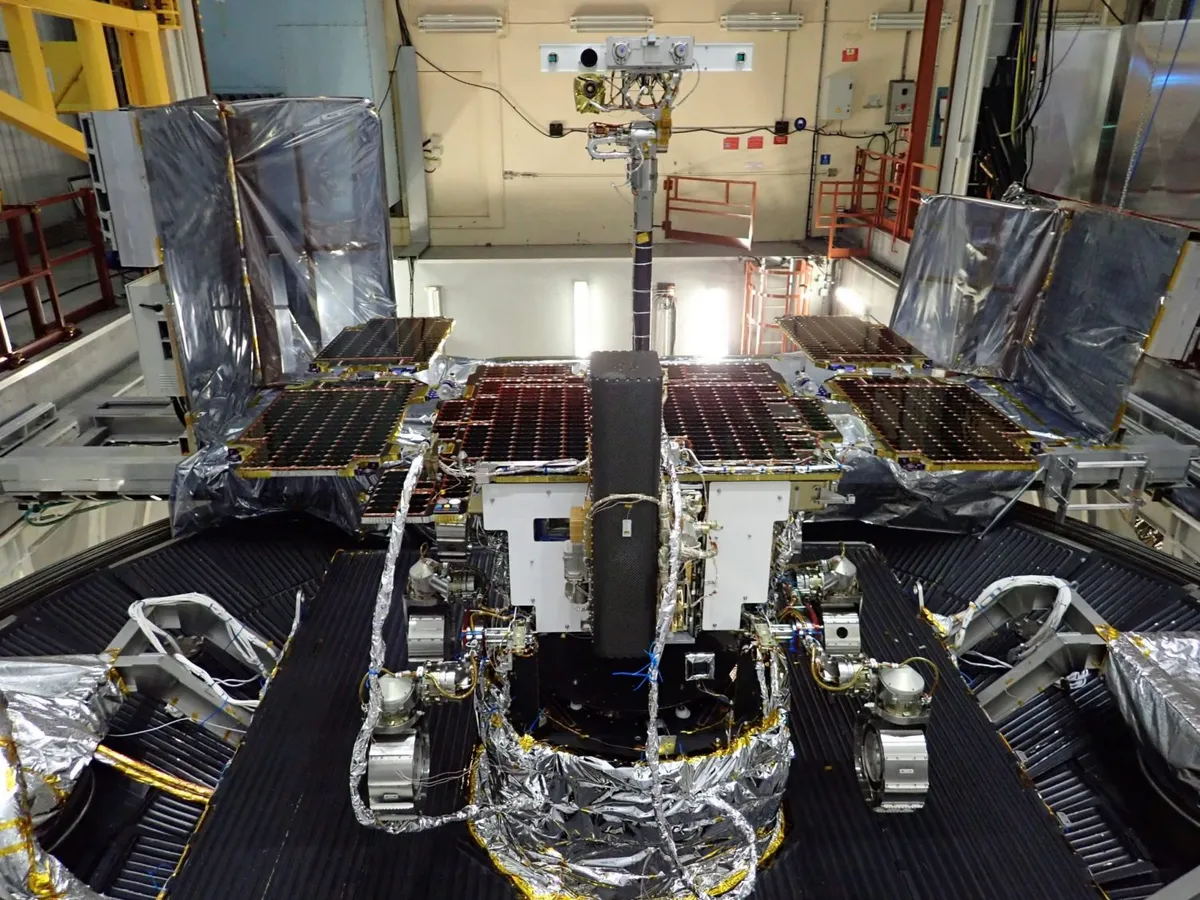

Rosalind Franklin Rover heads to the Red Planet

September will see the launch of the Rosalind Franklin rover towards Mars.

The rover was supposed to lift off in 2020, but problems with its parachutes pushed the schedule back by a few months, meaning it missed its launch window.

Now, 26 months later, Mars and Earth will align once again and it can start its journey.

The mission is a joint endeavour between the European Space Agency and the Russian space agency Roscosmos, and will hunt out the signs of past Martian life.

The rover’s biggest asset is a 2m-long drill that can reach deep down under the weather- and radiation-ravaged surface to where signs of past life might survive.

The onboard instruments will then be able to analyse the soil’s mineral composition, hunting out organic material, as these are the building blocks of life.

There is an air of trepidation surrounding the endeavour, however, as neither Europe nor Russia has had much luck landing on Mars in the past.

Of the 19 Russian and Soviet missions and two European attempts to land – including the Schiaparelli lander in 2016, intended to be a trial run of this landing – none has been fully successful.

Hopefully, the agencies have learned from their mistakes to ensure Rosalind Franklin’s success.

This article originally appeared in the January 2022 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.