The Saturn V rocket retains a mystique as the largest and most powerful rocket ever brought to operational status. Standing 110.6m tall – just shorter than St Paul’s Cathedral – the Saturn V carried five F-1 engines on its first stage, five J-2 engines on its second stage and a single J-2 on its third stage.

On 9 November 1967, veteran journalist Walter Cronkite struggled to make himself heard as the first Saturn V unleashed a raging torrent of flame and ponderously took flight for the Apollo 4 mission. Its raw, naked power was unmistakable.

Read more spaceflight history

“The building’s shaking,” he intoned. “This big blast window is shaking. We’re holding it with our hands. Oh, the roar is terrific! Part of our roof has come in here.”

His usual calmness and poise were momentarily lost, as his gruff voice notched up an octave to overcome the din.

On that day, Cronkite and the people of Florida were left wondering if a rocket had risen or Earth had sunk.

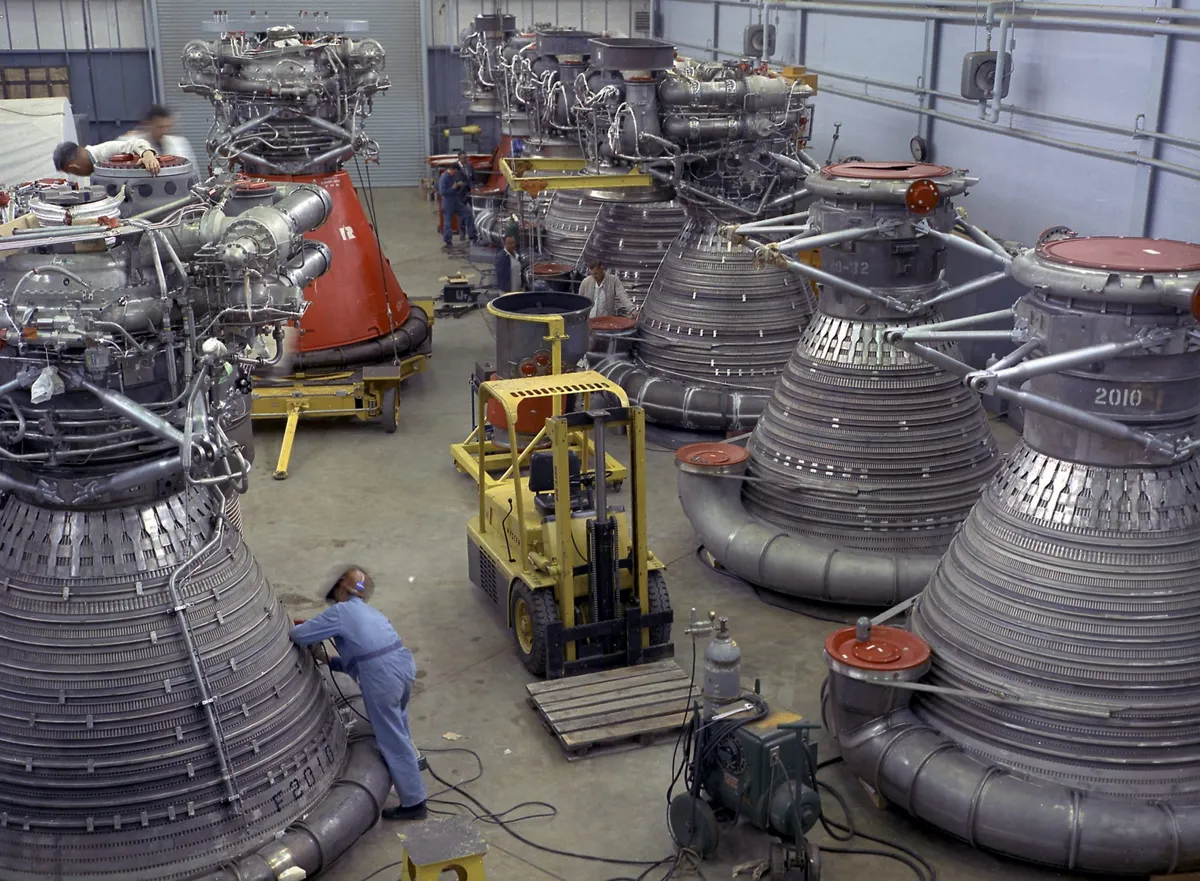

The F-1 remains the largest and most powerful single-chambered liquid-fuelled rocket engine ever developed, whilst the J-2 would fire twice to deliver astronauts into low-Earth orbit and onward to the Moon.

Half the size of its big brother, the J-2 was America’s largest hydrogen-powered engine until the development of the Space Shuttle’s RS-25.

It was also one of few engines of this period that could be ‘restarted’ in space.

Eighty-nine truckloads of liquid oxygen, 28 truckloads of liquid hydrogen and 27 railcars of kerosene were needed to power each launch.

That vast figure was not lost on transatlantic aviation pioneer Charles Lindbergh, who met the Apollo 8 crew in December 1968, just before Frank Borman, Jim Lovell and Bill Anders became the Saturn V’s first human passengers.

When Borman revealed that his rocket gorged 18,000kg of fuel every second, Lindbergh was astounded.

“In the first second of your flight,” he breathed, “you’ll burn 10 times more fuel than I did, all the way to Paris!”

Apollo 8 was humanity’s first piloted voyage to orbit the Moon, but the Saturn V’s previous unmanned flights saw mixed results.

Though Apollo 4 went smoothly, when Apollo 6 launched in April 1968 the F-1 engines suffered thrust fluctuations and the rocket ‘bounced’ violently, like a pogo stick.

Matters worsened when two second-stage engines shut down early. Then, after attaining a lopsided orbit, the third stage failed to restart for its second firing.

If astronauts had been aboard, their mission would have been aborted.

Between December 1968 and December 1972, 10 Apollo crews rode this beast into space.Four men braved it twice.

At lift off, the Saturn V pummelled the Earth with 3.4 million kg of thrust – equivalent to 160 million horsepower – and took 11 seconds to lumber clear of the launchpad.

Under the harsh guttural growl of the first stage, the astronauts breathing laboured under forces of 4.5G.

They were thrown against their harnesses as the 1st stage was jettisoned, then rammed back into their seats when the second stage ignited 3 minutes into flight. One astronaut compared it to sitting on a giant compressed spring.

At 9 minutes, the 2nd stage was discarded and the crisp, rattling 3rd stage took over.

And when its engine fell silent, 96% of the Saturn V’s launch weight was gone and the crew was moving at 37,300km per hour, faster than any humans ever before.

However, these launches were not without their share of drama. Apollo 10 suffered severe ‘pogo’ oscillations, thanks to a metal bar fitted behind the astronauts’ seats, whilst Apollo 12 flew into stormy skies and was twice struck by lightning.

This turned the rocket into the world’s longest lightning rod, opening a 2,000m electrical path from the engines to the ground.

One of Apollo 13’s J-2 engines shut down too soon, and on Apollo 15 the first and second stages came within a whisker of collision.

Then, on the Saturn V’s final launch, which would put the Skylab space station into orbit, vibrations during the launch ripped off shielding and a solar array, crippling the station.

The rocket was charged with meeting President John Kennedy’s goal of landing a man on the Moon, but was built with a broader scope in mind.

Initially capable of delivering 118,000kg into low-Earth orbit and 41,000kg to the Moon, later improvements to the F-1 engine raised this estimate by 18 percent during the later Apollo missions.

The Saturn V could have launched space stations, more Moon landings, a 400-day crewed flyby of Venus, robotic lunar and Martian rovers and even a scaled-up version of the Voyager interplanetary spacecraft.

In the first second of your flight you’ll burn 10 times more fuel than I did, all the way to Paris!

Charles Lindbergh

Those unrealised missions required a second production run of the rocket, with an upgraded suite of engines more powerful than its predecessors.

Other concepts included strap-on boosters and might even have carried the Space Shuttle. Today’s International Space Station could have been assembled decades sooner and in a handful of launches.

Sadly, the realities of life on Earth took their toll on a rocket which, in today’s economy, would consume $1.26 billion for a single flight.

At its most bloated phase of development, the Saturn V swallowed the equivalent of 80% of NASA’s current budget.

Faced with an unpopular war in Vietnam, a racially divided United States and parallel needs to tackle education and healthcare, the attention of successive White Houses was drawn away from space exploration.

A death-knell thus sounded on the Saturn V. Fifteen rockets were built, one of which launched Skylab and nine sent men to the Moon.

Three others tested Apollo in low-Earth orbit. Two were built for lunar landing that never happened and their unused hardware today gathers dust in Florida, Texas, Mississippi and at the National Space Museum in Washington, DC, gawped at daily by thousands of tourists.

Their ageing hulks serve as lonely sentinels, reminding us of past glories and a future that never came.

An unforgettable experience

From his seat aboard Apollo 8, Bill Anders saw a hornet fluttering outside the Saturn V, minutes before launch.

“She’s building a nest,” he mused, “and, boy, did she pick the wrong place to build it!”

Anders never saw the hornet again, but anything in the vicinity of the giant rocket as it left Earth was incinerated.

Even beach sand at Cape Kennedy was glazed to glass by the intense heat, which reached 3,300ºC.

From 5km away, the nearest unprotected human witnesses beheld the spectacle not only with their eyes and ears, but through the soles of their feet, as the ground shook and a continuous staccato crackle assaulted their chests.

Queen Fabiola of Belgium clutched her husband’s arm as the shockwave and unearthly howl of the Saturn V swept over them.

Even King Hussein of Jordan, who had seen many launches, flinched at the sight.

Similar emotions were at play for the astronauts’ families. Louise Shepard braced herself against a hurricane fence when a gloomy midwinter’s sky suddenly glowed white-hot as her husband took flight aboard Apollo 14.

For the astronauts themselves, attitudes differed. Mike Collins called the Saturn V “a gentleman”, whilst Gene Cernan labelled it “absolutely scary”.

For Buzz Aldrin and Frank Borman the lasting memory was of a distant rolling thunder, then a sideways vibration so harsh that they could hardly read their instruments.

Others remembered a profound sense of helplessness as an imperceptible sense of movement gave way to a powerful jackhammering motion.

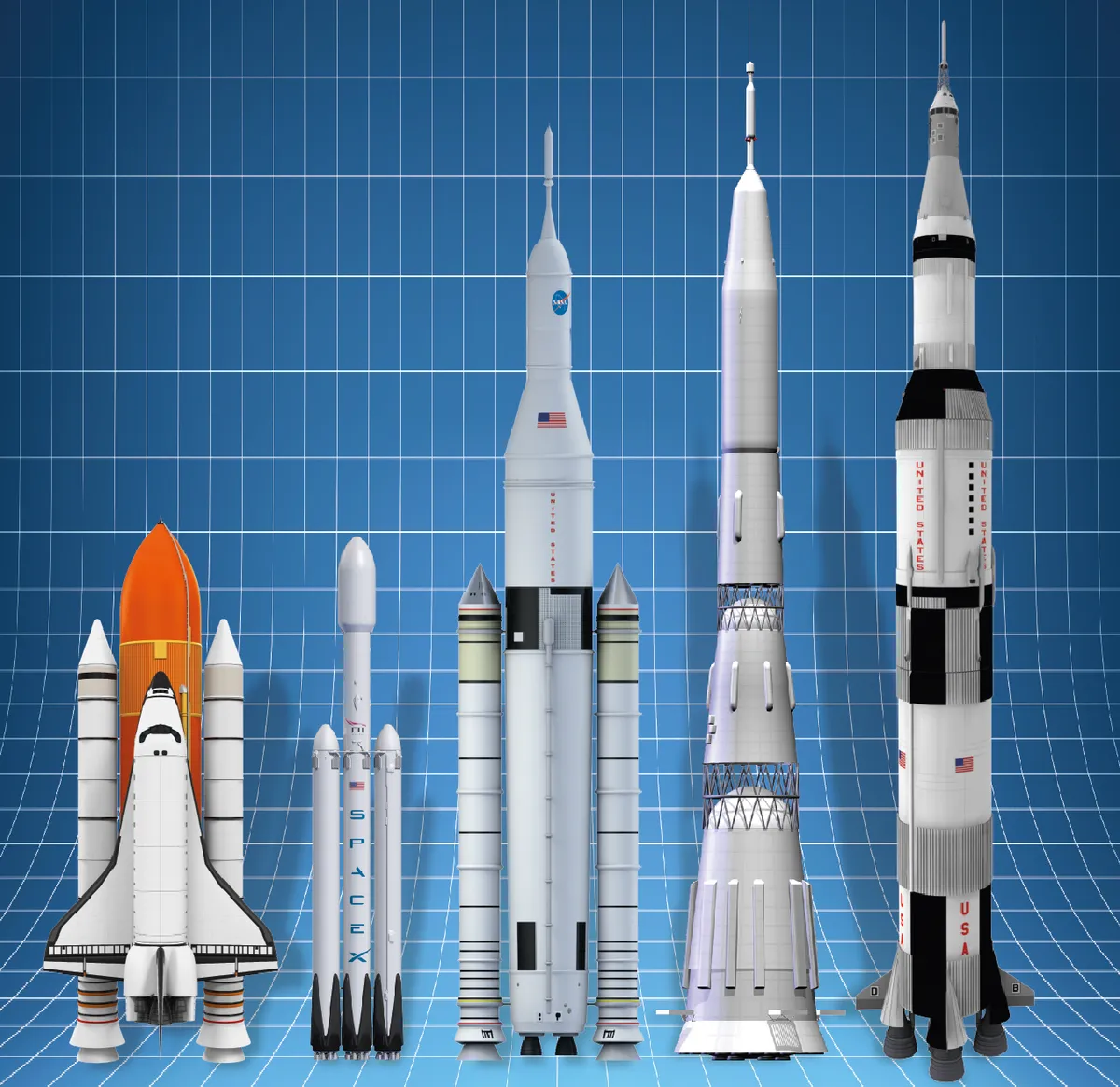

A giant amongst giants

How other rockets, past and present, measure up against the Saturn V

Space Shuttle

- Payload capability 27,500kg to low-Earth orbit

- Shuttle height 56.1m

- Weight 2.1 million kg

- Lift off thrust 3.5 million kg

- Flight history Flew 135 times between April 1981 and July 2011

Falcon Heavy

- Payload capability 63,800kg to low-Earth orbit

- Height 70m

- Weight 1.4 million kg

- Lift off thrust 2.3 million kg

- Flight history First flight expected no earlier than November 2017

Space Launch System (SLS)

- Payload capability 130,000kg to low-Earth orbit in fully evolved configuration

- Height 98.1m

- Weight 2.7 million kg

- Lift off Thrust 4.2 million kg

- Flight history First flight no earlier than 2019

N-1

- Payload capability 95,000kg to low-Earth orbit and 23,500kg to the Moon

- Height 105m

- Weight 2.7 million kg

- Lift off thrust 4.6 million kg

- Flight history Flew four times between February 1969 and November 1972

Saturn V

- Payload capability 118,000kg to low-Earth orbit and 41,000kg to the Moon

- Height 110.6m

- Weight 2.9 million kg

- Lift off thrust 3.4 million kg

- Flight history Flew 13 times between November 1967 and May 1973

Ben Evans has written nine books on space exploration and is the senior writer for AmericaSpace. This article originally appeared in the November 2017 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.