Earth was once regarded as a cosmic oddity. We knew there were an almost countless number of stars like our Sun, and no reason why there shouldn't be other planetary systems similar to ours. But there was no proof.

Some astronomers believed planets might be common, but others were more cautious, and were very dubious about this.

The main problem was we could not hope to see many of these planets in orbit around distant stars directly; we would have to rely on other methods to identify the ‘extrasolar’ planets, or exoplanets.

Personally, I was confident that other planets were very numerous, but there were always doubts.

I well remember saying, "I will believe in the existence of exoplanets as soon as I actually see one," but when this would be – if ever – I did not know.

nd certainly I know some astronomers who believed that the number of extrasolar planets in our Galaxy would be less than a dozen.

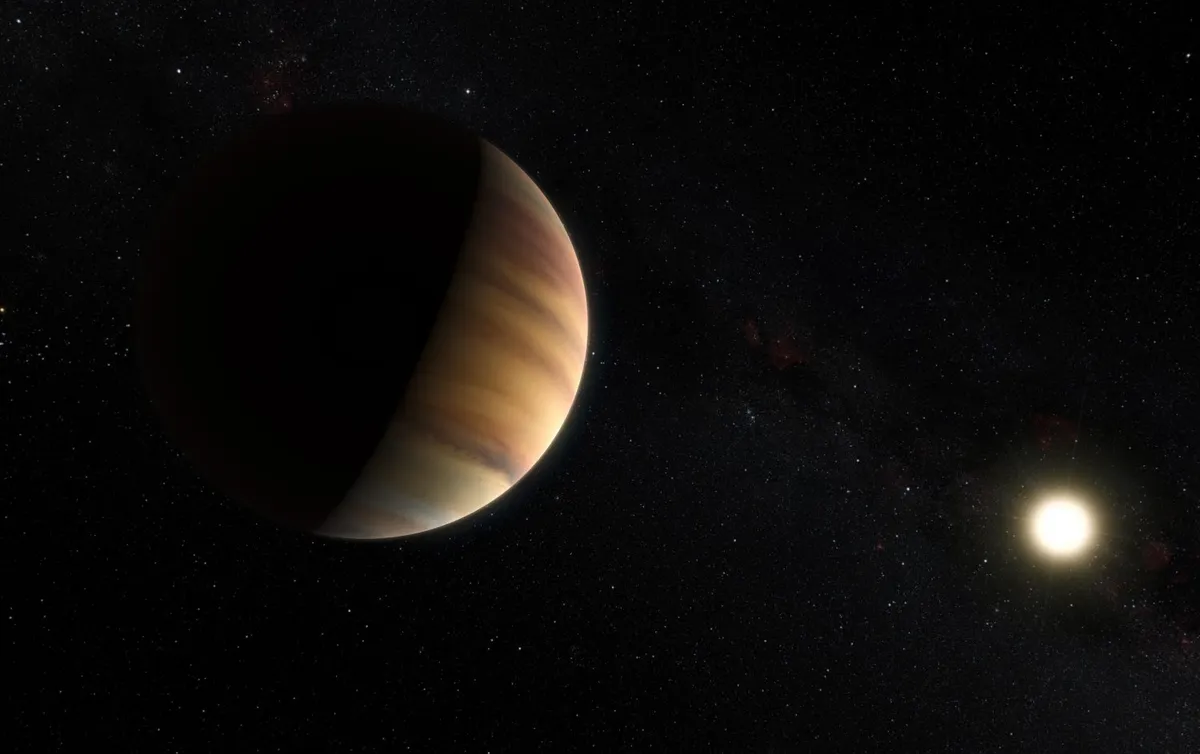

The situation was altered in 1995 when studies of a very ordinary

looking star – 51 Pegasi – ushered in a new era.

Astronomers announced that they had discovered a planetary-mass companion in orbit around it, which they called 51 Pegasi b and has subsequently been informally named Bellerophon.

You can find 51 Pegasi with no trouble at all: with a magnitude of +5.5, it is visible to the naked eye, a little way away from an imaginary line connecting the two right-hand stars of the Great Square of Pegasus.

The discovery of its companion planet was made spectroscopically; it was found that the star showed movements, which indicated the presence of a planetary body associated with it.

The great breakthrough had been made and was quickly confirmed by other astronomers using different spectroscopic equipment.

Even if planets such as this could not actually be seen, we could be confident that they really existed.

At the time of writing, over 700 exoplanets have been found (NB: that number has now reached over 5,000 exoplanets).

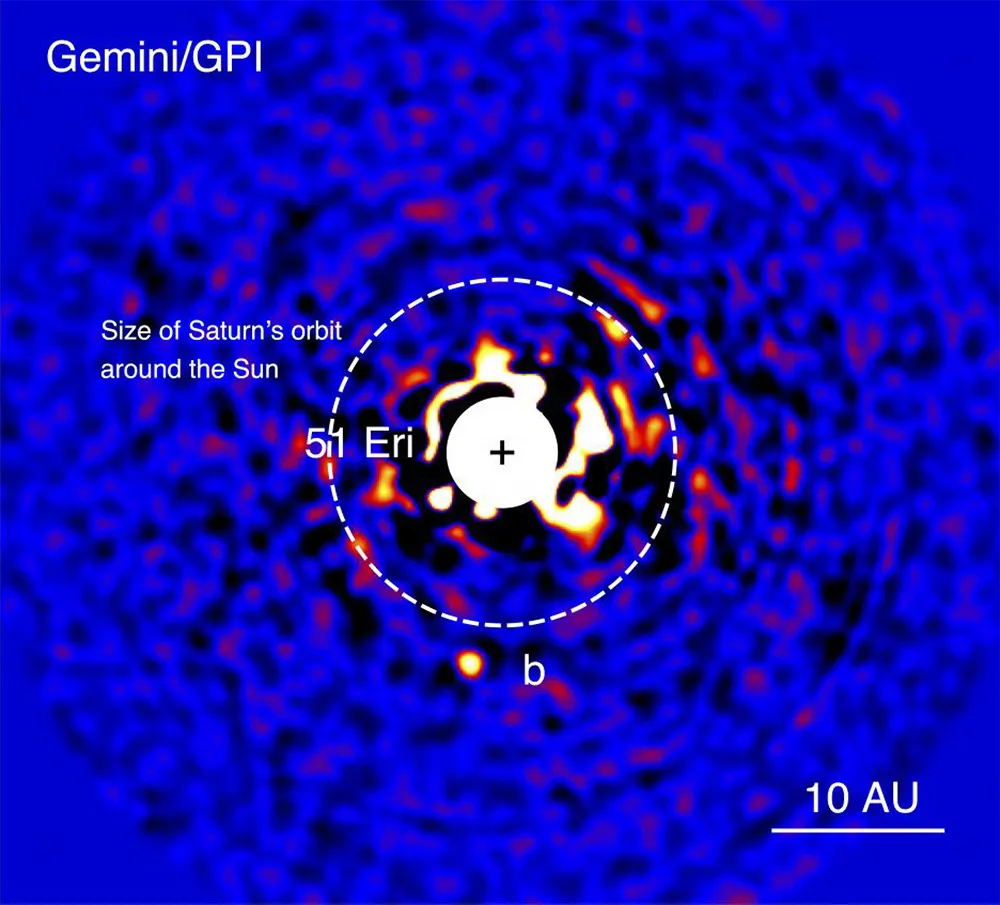

There are even one or two cases in which the exoplanet has been directly viewed, showing up as only a faint dot of light.

Remember, we are dealing in interstellar distances of many lightyears, and on this scale, the distance between Earth and the Sun is very small – less than 10 lightminutes.

How we find exoplanets

So what are the main methods of finding exoplanets?

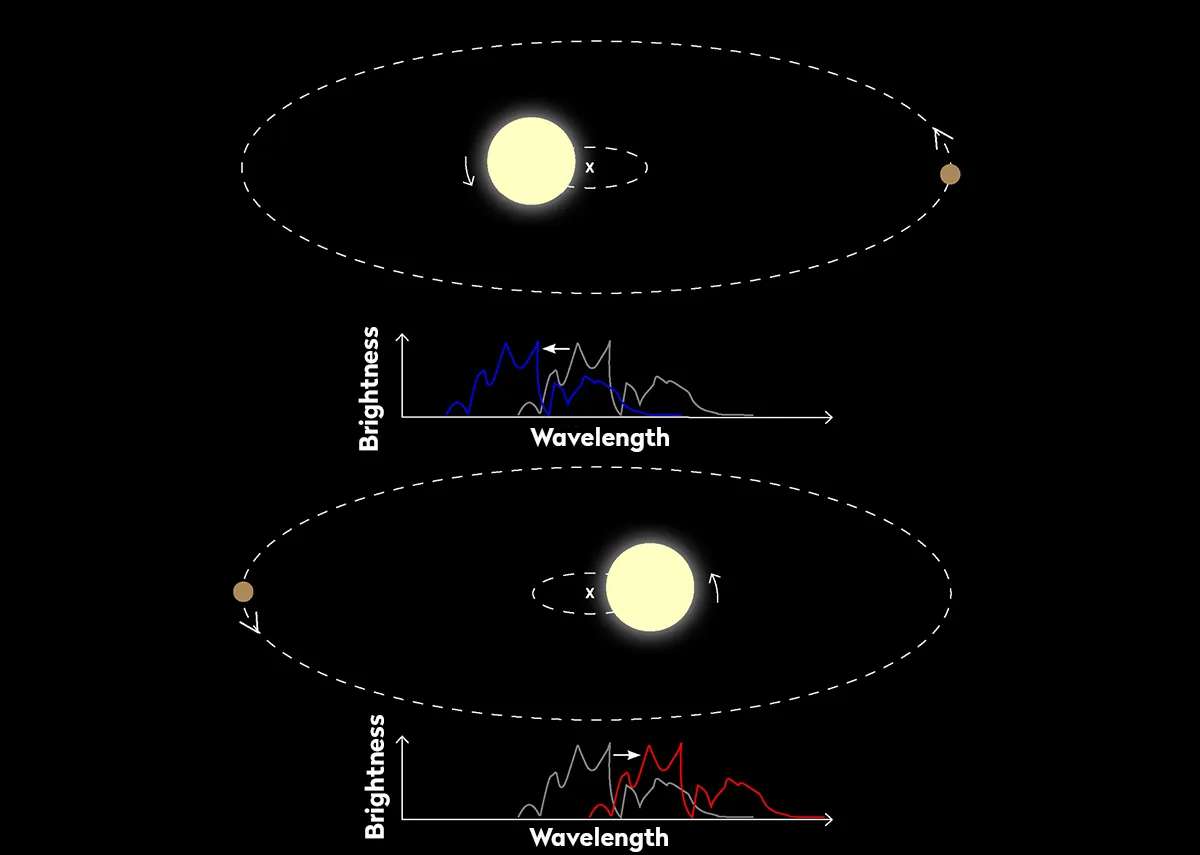

Probably the most reliable is known as radial velocity, a technique that measures a star’s wobble, produced by a planet orbiting around it.

These wobbles can be observed as Doppler shifts in the spectrum of the light from the parent star.

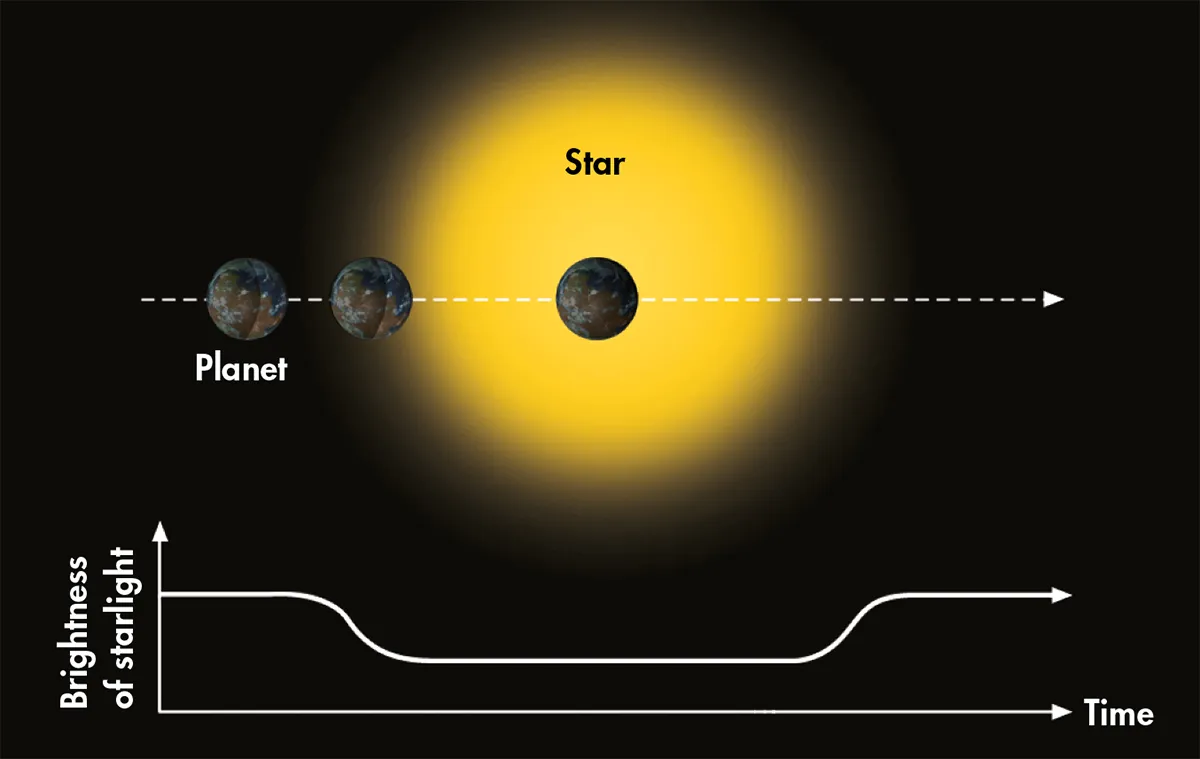

Second is the transit method, in which astronomers measure the tiny drop in light caused by an orbiting planet passing in front of the face of its star, as seen from Earth.

Of course, this means the planet must be of considerable size.

Go out to a distance of several lightyears from the Sun and, if you have good enough equipment, you will see the tiny diminution of light that occurs when Jupiter passes across it.

This method is clearly limited, because a small world such as Earth would cause a very small dimming.

All in all, it is safe to say that one question has been solved: exoplanets not only exist, but are very numerous.

Our main problem is that the methods currently available to us are more suitable for tracking down giant worlds, more like Jupiter than like Earth.

However, it is surely reasonable to assume that if there are large planets, there are also small ones, even if they are more difficult to detect.

Life on exoplanets

I doubt if there are any astronomers who now question the fact that exoplanets are very numerous indeed, and this brings us on to a second vital question.

But what makes a planet habitable? Can any of these planets be capable of supporting life?

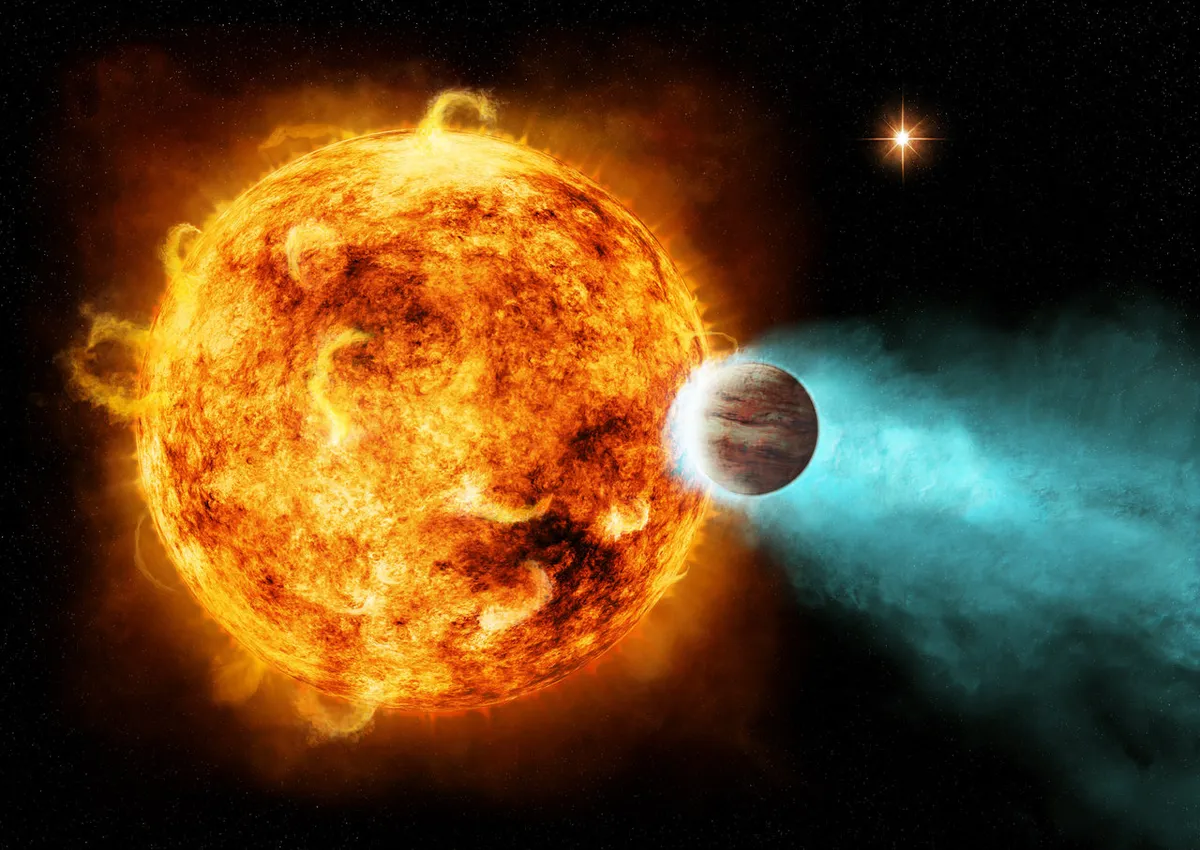

Gas giants such as Jupiter presumably cannot, at least if we are dealing with life of the kind that you and I would know.

To find a world where there could be beings of our type brings us on to quite a different problem.

Here there are very conflicting views: some astronomers are very confident that Earth-type life is common but others disagree, and I know of at least one eminent authority, widely respected all over the world, who believes that Earth-type life must be vanishingly rare.

He will go as far as to claim that we are the only intelligent race in our Galaxy.

It is not easy to see how telescopic or spectroscopic investigations can give us any kind of answer.

Life can take may forms, even here on Earth, but so far as we know all life is based upon carbon, and once we depart from this we enter the realm of pure speculation.

There is not much outward resemblance between a man, a mouse and a jellyfish, yet they are all based on carbon and represent the kind of life we can understand.

I am prepared to accept the existence of an astronomer who looks like a cabbage and squeaks like a bat – on the other hand I am much more dubious about a living creature that breathes carbon dioxide and eats pure iron.

So I think in our search for life we must confine ourselves to carbon-based life.

Once we go beyond this into entirely alien forms, speculation becomes endless and the search becomes, frankly, pointless.

We have detected many exoplanets by indirect methods and very few people now seriously deny their existence.

Earth-like planets capable of supporting our type of life are also accepted by most people and we can be fairly confident that there are many millions of

worlds where life could exist.

But if life can appear on a world such as Earth, will it?

This is our next problem, and if I was to be asked about it in, shall we say, 20 years time, I may be able to give you a definite answer.

Until then I can only say, wait and see!

This article appeared in the March 2012 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.