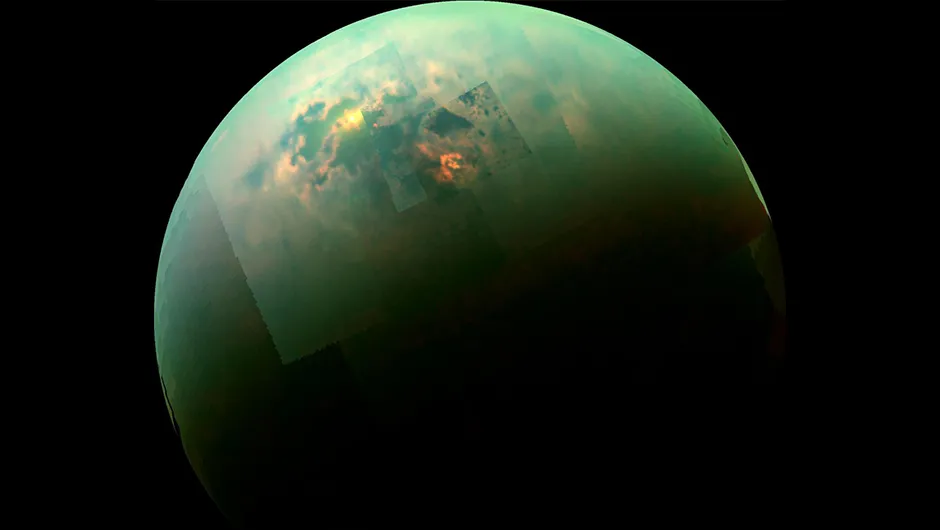

In the search for life beyond Earth, one of the most promising places in our Solar System isn't a planet at all; it's Saturn’s largest moon, Titan.

Wrapped in a thick, smoggy yellow haze and nearly as cold as Neptune, Titan is a world of extremes.

More on Titan

And yet, it's one of the most Earth-like places in the Solar System because it also has something rare in our cosmic neighbourhood: weather.

Titan's atmosphere is mostly nitrogen and has clouds and rain, just like Earth.

But unlike Earth, whose weather is driven by a water cycle, Titan has a methane (CH4) cycle.

Methane evaporates from the surface and rises into Titan's atmosphere, condensing to form methane clouds.

Then it falls as cold, viscous rain onto a frozen water-ice surface.

Thanks to a powerful pairing of the James Webb Space Telescope and the ground-based Keck II telescope in Hawaii, scientists have captured clouds rising through Titan’s atmosphere in its northern hemisphere.

It's the first clear sign of cloud convection in the region, a dynamic weather process similar to Earth’s own storms.

Titan's weather

"Titan is the only other place in our Solar System that has weather like Earth, in the sense that it has clouds and rainfall onto a surface," says Conor Nixon of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, lead author of the study.

On Titan, the rain isn't water, it’s liquid methane and ethane.

Temperatures on Titan's surface are around –179°C (–290°F), cold enough that water is frozen solid like rock.

And methane acts on Titan like water does on Earth, rising through the atmosphere, forming clouds and falling as rain to fill lakes and seas

Those lakes are mostly in Titan’s northern hemisphere, right where Webb and Keck spotted the new cloud activity.

Seeing weather on another world

The Webb and Keck observations of Titan's clouds were made late 2022 and mid-2023, at the end of summer in the moon's northern hemisphere.

Thanks to their ability to see in different wavelengths of infrared, Webb and Keck were able to peer through Titan’s hazy atmosphere and observe clouds at different altitudes.

They found the clouds not only exist at northern latitudes, but they appear to rise over time, a hallmark of convection, the process that drives thunderstorms on Earth.

This is the first time such activity has been confirmed in the northern hemisphere on Titan. Until now, it had only been seen in the southern hemisphere.

"Webb’s observations were taken at the end of Titan’s northern summer, which is a season that we were unable to observe with the Cassini-Huygens mission," says Thomas Cornet of the European Space Agency, a co-author of the study.

"Together with ground-based observations, Webb is giving us precious new insights into Titan’s atmosphere, that we hope to be able to investigate much closer-up in the future with a possible ESA mission to visit the Saturn system."

Weather... and life?

Weather isn’t the only thing Titan shares with Earth. It also has complex organic chemistry, meaning chemistry containing carbon, the building blocks of life as we know it.

Methane in Titan's atmosphere gets broken apart by sunlight and by energetic particles from Saturn’s magnetic field.

Once split, these carbon-rich fragments recombine into a cocktail of more complex molecules, such as ethane and other hydrocarbons.

Webb detected one of the key intermediates in that chemical process, the methyl radical (CH₃).

It’s called 'radical' because it has a free electron, making it a central ingredient in the chemical processes that build larger, more complex molecules.

"For the first time we can see the chemical cake while it’s rising in the oven, instead of just the starting ingredients of flour and sugar, and then the final, iced cake," says study co-author Stefanie Milam of the Goddard Space Flight Center.

Investigations and data like these are key for astrobiologists trying to understand how life might emerge in different environments beyond Earth.

Titan’s chemistry exists in a much colder setting than on Earth, but still involves many of the same building blocks.

Could Titan host some form of life? It’s unlikely to be anything like life on Earth, given the extreme cold and lack of liquid water.

But Titan could be a laboratory for understanding what kinds of chemistry are possible on other worlds, and how life might begin elsewhere in the Universe.

Credits: NASA/JPL/Univ. Arizona/Univ. Idaho

A world coming to an end?

Nothing lasts forever, and that's especially true in space.

Titan’s rich methane atmosphere may be depleting over time.

Methane is being broken down and lost to space on Titan, just as water was slowly stripped from Mars.

"On Titan, methane is a consumable," says Nixon.

"It’s possible that it is being constantly resupplied and fizzing out of the crust and interior over billions of years.

"If not, eventually it will all be gone and Titan will become a mostly airless world of dust and dunes."

For now though, missions like Cassini-Huygens and the James Webb Space Telescope – and who knows what future missions – are giving us an unprecedented glimpse into this strange, yet oddly familiar, icy Saturnian moon.