My colleague Michel Mayor and I made the first discovery of a planet orbiting an ordinary star outside our own Solar System.

That was in 1995. Since then, telescopes on Earth and in space have detected more than 5,000 exoplanets.

Our pioneering discovery was made at the Observatoire de Haute-Provence in France using the radial velocity method, which measures the wobble of a star as it is orbited by another body.

Our find came when it did thanks to a number of small but simultaneous advances in technology and computing power that allowed us to examine real-time data from a star labelled 51 in the constellation of Pegasus.

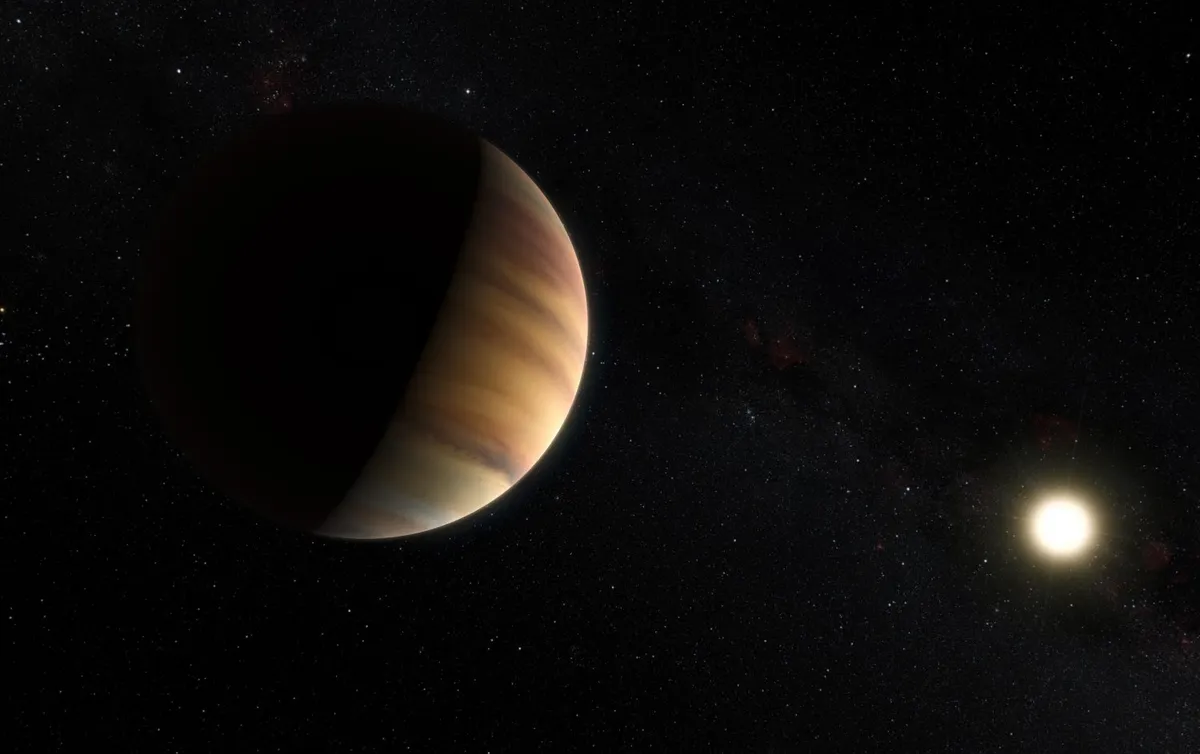

The exoplanet was immediately obvious and really bizarre.

No one had expected then to find a planet with an orbit lasting just four days. Many people just didn’t believe it.

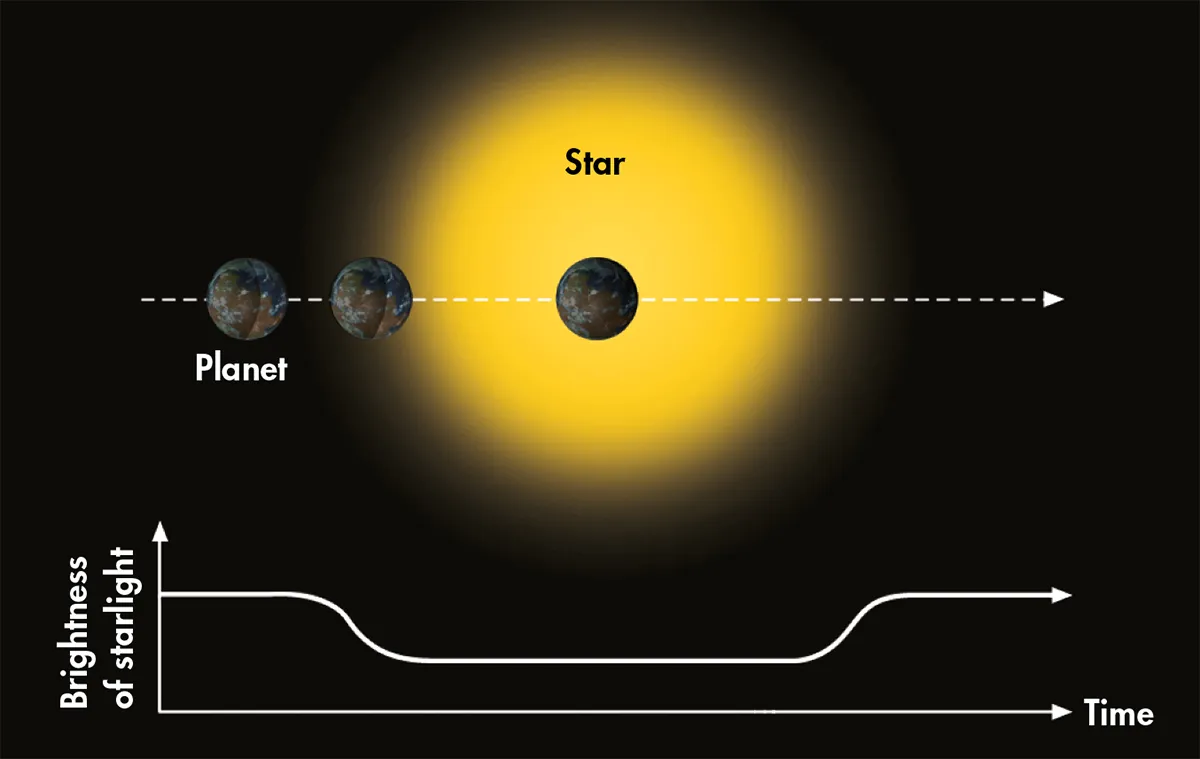

More discoveries soon followed. The next revolution in exoplanet hunting came a few years later with a technique called the transit method, where the exoplanet reveals itself by passing in front of its home star.

The first such find, in 1999, confirmed a planet already discovered by radial velocity. It confirmed to the skeptics that exoplanets were real and not imaginary.

NASA’s Kepler space telescope has been the ultimate transit machine, discovering many hundreds of exoplanets on its mission in space.

Most of the planets it has found have been different from those in our Solar System, and we don’t really know much about them.

But we are coming to the very interesting conclusion that our own Solar System is rather unusual.

The search for exoplanets was meant to help us understand the Solar System, and yet the more we look outside, the less we understand ourselves.

Research so far has demonstrated that just about every star has planets. The focus in the next 20 years will be to understand what they are like, and to see how far we can go to finding a Solar System like our own.

One major goal is to try to find a twin planet to Earth. Kepler was meant to do that and failed: instead it showed us that we were too focused on trying to find something equivalent to our own world.

The next generation of space telescopes are TESS, CHEOPS and PLATO, which will target nearby stars and attempt to discover and characterise their planets.

These missions will give us basic information such as the density of an exoplanet.

After that we expect to learn about its atmosphere, including its chemical composition.

We will even be able to observe clouds. So this is the challenge for the next 10 to 20 years.

In time we will find an object like Earth, with a thin atmosphere, and then one day we might even see some evidence in that atmosphere of life.

The James Webb Space Telescope is playing a very important role in this, as will the new giant ground instruments such as the Extremely Large Telescope in Chile.

These new giant telescopes will, in time, be able to image nearby exoplanets directly and tell us much more about these alien worlds.

Developing technology will allow us to check how they rotate, their seasons and climate, and see whether they are habitable.

It is not very clear whether we would recognise signs of life, or how long that will take, but if we keep looking, we should find something.

We are working really hard right now to find targets for the new generation of giant telescopes to observe.

One thing that is clear, however, is that we must avoid being too target-oriented over the next 20 years.

The story of science, as already demonstrated with exoplanets, is that we have to be ready for the unexpected.

This article originally appeared in the June 2015 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.